Democracy of Sound (12 page)

Read Democracy of Sound Online

Authors: Alex Sayf Cummings

Tags: #Music, #Recording & Reproduction, #History, #Social History

As bootlegging spread in the late 1940s, a court case tested the limits of property rights for recorded sound, resulting in a decision that left the door open to piracy. A ruling by the US District Court for Northern Illinois,

Shapiro, Bernstein v. Miracle Records

(1950) dealt with the ownership of a particular interpretation of a musical idea, as embodied in a record.

81

While working as a groundskeeper at Chicago’s White Sox stadium, pianist Jimmy Yancey helped develop boogie woogie, a genre of jazz that focused more fully on the piano than did any other form. He taught the style to Meade Lux Lewis, who wrote and recorded the tune “Yancey Special” in his fellow pianist’s honor. When Lewis later sued another company for allegedly copying “Yancey Special,” Yancey himself came forward and insisted that the composition did not originate with Lewis anyway, thus rendering his infringement claim meaningless. Justice Michael Igoe, in turn, ruled that all these claims were irrelevant, since the similarity between the compositions was simply too basic to warrant copyright protection. The only thing the recordings have in common, he wrote, is “a mechanical application of a simple harmonious chord.”

82

In other words, the distinctive rhythm of “Yancey Special” was not a copyrightable expression. “The purpose of copyright law is to protect creation,” Justice Igoe wrote, “not mechanical skill,” which is all the innovations of boogie woogie amounted to in the eyes of the court.

83

If anything, what was copied was

not a song, but a new genre or style of performance. Justice Learned Hand had ruled similarly in 1940, when his decision in the case

RCA v. Whiteman

held that the US Copyright Act did not allow for individual recorded performances to be owned. Although Hand had conceded that a recording might contain some elements of genuine creativity, the law simply did not provide copyright for various interpretations of the same composition. In Igoe’s view, Yancey and Lewis were merely arguing over different ways of playing a tune, not a copyrightable expression.

84

As Bill Russell observed in one of the earliest studies of the new genre, many critics alleged that “the Boogie Woogie has no melody.” Yet melody was the solid core of written music, as traditionally protected by copyright. If the

Miracle

opinion held, there would be nothing copyrightable about the frenetic improvisation that made up a recording by boogie artists Pine Top Smith or Cripple Clarence Lofton. The rapid-fire piano pieces danced around a theme, consisting “of simple and logical yet satisfying patterns of notes in a limited range, usually proceeding conjunctly,” in Russell’s words. “Often in the more elaborate melodic texture there is incessant arabesque and figuration based on the essential notes of the melody.”

85

Igoe’s ruling would seem to rule out protection not just for “Yancey Special” and its imitators but also for a whole species of jazz whose originality derived from nimble involutions of a tune that sounded only like “mechanical skill” to the judge’s ears. US copyright only protected written compositions, and neither Lewis nor Yancey could claim to own the unique style that characterized their recordings. The decision showed how existing copyright law failed to address elements of distinctiveness and value that could be found only in a recorded performance, such as the improvisation that distinguished Yancey’s work. The Yancey case also prompted a wave of anxiety in the recording industry about whether their products would be copied by other firms. Since the decision came from a district court in Chicago,

Variety

suggested that it spawned a bootlegging boom in the Midwest.

86

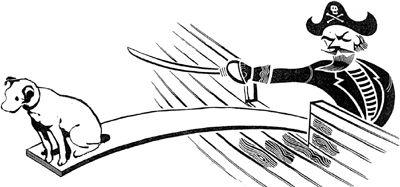

Figure 2.4

The December 1951 issue of

Record Changer

lampoons RCA Victor’s unwitting involvement in bootlegging by showing the iconic dog Nipper walking the plank.

Source

: Courtesy of the Brad McCuen Collection, Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University. Reprinted by permission of Richard Hadlock.

Fears of a fresh wave of bootlegging were realized in 1951 when a major label was caught pirating its own records. “RCA

Victor

, sworn enemy of disc piracy, is currently engaged in pressing illicit

Victor

and

Columbia

LPs for one of the most blatant of the bootleggers!” howled the

Record Changer

, a jazz collectors’ magazine, on the cover of its November 1951 issue. RCA ran a custom pressing service that manufactured small batches of records for labels that were too small to have their own facilities. One such outfit was Jolly Roger, which had contracted with RCA during the summer of 1951 to press hundreds of records at a cost of 65 cents a piece.

87

“Without exception, this material consisted of master acetates made from old

Victor

and

Columbia

sides strung together to form long-playing records,”

Record Changer

observed.

88

Jolly Roger compiled unique LPs of recordings that the likes of Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton had made for Victor, as well as some tunes from the Columbia catalog. The outfit also had RCA press records of Louis Armstrong, who remained, unlike Morton and Bechet, one of the biggest stars of contemporary jazz. Anyone in the industry should have realized that he would not be recording for such an obscure label,

Record Changer

argued.

89

The situation was particularly embarrassing because the record companies had just started making noise about piracy or “disk-legging.”

Variety

reported that the Harry Fox Agency, representative of song publishers, had begun investigating bootleggers at the behest of the labels in August 1951. The entertainment industry rag reported that the records were being wholesaled in batches of 500 at 30 cents a piece.

90

The number of records accords with the accounts of other pirates, who spoke of a range of up to 1,000 copies. RCA had actually become one of the loudest critics of piracy in the months prior to the Jolly Roger revelation. The company announced in September that it would begin retaliating against pirates. “Up until recently, the bootleggers had more or less confined themselves to the jazz field, where they sold dubs of the out-of-print Victor collector items,”

Variety

said. “In recent months, however, several bootleg firms have been distributing straight copies of current Victor hits under a variety of labels.”

91

Little did the company’s leaders realize that their own employees were helping the bootleggers raid the Victor catalog, using their own facilities. As the

Record Changer

deadpanned, “One high RCA spokesman had heatedly informed us that they would ‘seek injunctions and damages, prosecute, throw into jail and put out of business’ not only the operators of bootleg labels but also those processing and pressing plants that serve them (apparently considering the latter as guilty as the former).”

92

The bootleggers’ chutzpah had pushed their activities into the open. Dante Bollettino, a young jazz enthusiast, had run Jolly Roger’s parent company, Paradox Industries, for three years prior to his run-in with the law in 1951. Prior to Jolly Roger, his Pax label had released elegant reissues of musicians such as Cripple Clarence Lofton, the Chicago boogie woogie pioneer who influenced the likes of Meade Lux Lewis and Jimmy Yancey.

93

The back covers of Pax records featured detailed liner notes by Bollettino and jazz writers such as George Hoefer, which described the historical significance of the music and, in many cases, told of when and where the performances were recorded.

94

The label, based in Union City, New Jersey, promised “Records for the connoisseur,” compiling anthologies like

New Orleans Stylings

and

Americans Abroad: Jazztime in Paris

, which culled the best of lesser-known artists.

95

Jolly Roger, in contrast, dared to go further. There was the swagger of the name, and the fact that Bollettino had marched right into enemy territory to have his records made. “They [RCA] apparently did not react at all when confronted with a label that every schoolboy would know meant, by definition, ‘a pirate flag,’” marveled the editors of the

Record Changer

. “Record bootlegging is just as often referred to as record piracy … catch on, Victor?”

96

The label also reproduced fare that was not quite as obscure as Pax’s. A Jolly Roger catalog from the early 1950s lists one Frank Sinatra, two Bessie Smiths, and seven different Louis Armstrong records.

97

While some of the performances were out-of-print, names like Armstrong and Sinatra were bound to raise some eyebrows eventually. Jolly Roger records featured the same style of starkly colorful and iconic covers as Pax records had, but they lacked the liner notes and other identifying features. Their back covers were blank.

98

Perhaps Bollettino realized that the Jolly Roger venture might elicit more attention and wanted to minimize his own mark on the records.

In any case, he had gone too far. Armstrong and Columbia sued Paradox in February 1952, and the story made headlines in

Business Week

and

Newsweek

. Seeking an injunction, the plaintiffs cited the

Metropolitan

decision of two years prior.

99

“This marked the record industry’s first major reaction to the bootlegging problem,”

Business Week

noted.

100

Facing the legal might of the music business, Bollettino decided to settle out of court. “My lawyer insisted that we had a good case and could win, but I knew the record companies would feel they couldn’t afford to lose and would throw in everything they had,” he reflected in 1970, sitting in a fabric shop he had opened in Greenwich Village. “I was only twenty-three and didn’t have the money for a long expensive court case … But afterwards the big companies began to reissue more jazz records, so maybe I accomplished something after all.”

101

For Bollettino, the bigger goal was to ensure that at least some of the music he copied would continue to be available to the public.

Perhaps Bollettino and his fellow pirates simply drew too much attention. They proved the viability of a market that the big record labels had left fallow and, in fact, relinquished to collectors for years. “Disk bootleggers, who have been coining considerable profit from their operation of selling dubs of cut-out jazz sides, are being rapidly squeezed out of business,”

Variety

declared, as the major labels started their own reissue programs.

102

However, Bollettino shot back at the industry. “Columbia and the ‘majors’ have failed to make or keep jazz records available to the public,” he told the press. “Their few reissue programs have started out with a big hullabaloo and fizzled out simply because it is not profitable to try to sell a few thousand copies of a record … Only a small firm with low overhead can profitably reissue such records.”

103

Though torn, the jazz writers echoed this criticism of the major labels, saying that the companies had failed to honor their responsibilities as custodians of culture. Some of the majors had tried reissues, but “usually it only served to emphasize the gap between ‘their’ standards and ‘ours,’” the editors of

Record Changer

opined. “There is much more to jazz than Armstrong and Goodman and a scattering of sides by a few other people, although obviously you can come closer to breaking even or showing a profit with those names.”

104

An obscure Bix Beiderbecke record was not worth the time and money of a promotional machine that was accustomed to manufacturing records en masse and hyping them nationwide. Regardless,

Record Changer

’s publisher Bill Grauer, the jazz writer John Hammond, and the bootlegger Sam Meltzer all claimed to have been rebuffed when they sought to reissue old recordings legally by obtaining licenses from the major labels. In doing so, these critics maintained, the companies denied the public a portion of its heritage. “It involves a moral and artistic burden that they automatically took on when they first decided to make their money in part by the commercial recording and distribution of material that ‘belongs’ (by virtue of its cultural significance) to the people as a whole,” a

Record Changer

editorial argued.

105

Elsewhere, the editors wrote, “We are not so naïve as to believe that all, or even many, bootleggers are motivated solely, or even partly, by noble impulses.” Still, their activities served the public when scarce music was preserved and perpetuated.

106