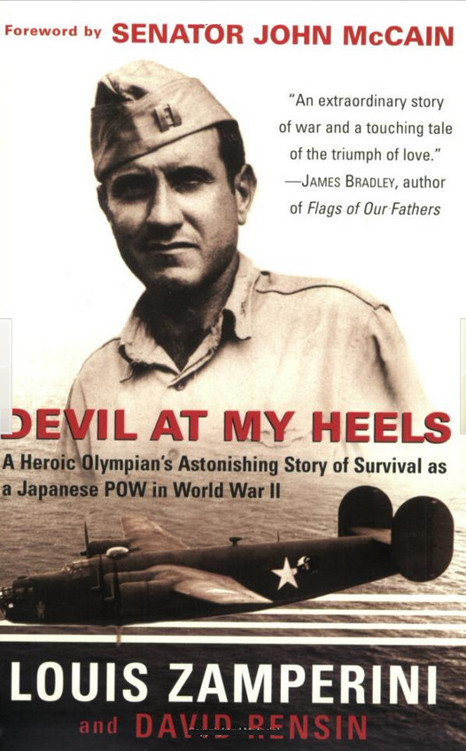

Devil at My Heels: The Story of Louis Zamperini

Read Devil at My Heels: The Story of Louis Zamperini Online

Authors: Louis Zamperini

Tags: #Track & Field, #Running & Jogging, #Sports & Recreation, #Converts, #Christian Converts, #Track and Field Athletes

A Heroic Olympian’s Astonishing Story of Survival as a Japanese POW in World War II

with David Rensin

For Cynthia, my children Cissy and Luke,

and my grandson, Clayton

The 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the

Treatment of Prisoners of War

Article 2:

Prisoners of war are in the power of the hostile Power, but not of the individuals or corps who have captured them. They must at all times be humanely treated and protected, particularly against acts of violence, insults and public curiosity. Measures of reprisal against them are prohibited.

A smooth sea never made a good sailor.

—Anonymous

SENATOR JOHN McCAIN

L

ouis Zamperini’s life is a story that befits the greatness of the country he served: how a commonly flawed but uncommonly talented man was redeemed by service to a cause greater than himself and stretched by faith in something bigger to look beyond the short horizons of the everyday.What he found, beyond the horror of the prison camps and the ghosts he carried home with him, is inspiring.

The remarkable life story of “Lucky Louie” takes him from the track as an Olympic runner in Berlin in 1936, where he met Hitler, to a raft in the Pacific fending off man-eating sharks and Japanese gunners to prisoner of war camps where rare goodness coexisted with profound evil to a hero’s return to America, where he would first plumb the depths of despair and self-destruction before soaring to heights he could not have foreseen or imagined.

This book contains the wisdom of a life well lived, by a man who sacrificed more for it than many people would dare to imagine. It is brutally honest and touchingly human, comfortably pedestrian and spiritually expansive. It should invoke patriotic pride in readers who will marvel at what Louis and his fellow prisoners gave for America, and what we gained by their service. It holds lessons for all of us, who live in comfort and with plenty in a time of relative peace, about what we live for.

More than a story of war, its lessons grow out of Louis’s wartime experience. Its moral force is derived from the very immorality of American prisoners’ savage treatment by their wartime captors, and the way Louis would ultimately drive away their demons. Rather than destroying Louis’s moral code, war and recovery from war’s deprivations revealed the mystery of Louis’s faith in causes far greater than the requirements of survival in a temple of horrors.

Whether in religion, country, family, or the quality of human goodness, faith sustains the struggle of men at war. Before I went off to war, the truth of war, of honor and courage, was obscure to me, hidden in the peculiar language of men who had gone to war and been changed forever by the experience. I had thought glory was the object of war, and all glory was self-glory.

Like Louis Zamperini, I learned the truth in war:There are greater pursuits than self-seeking. Glory is not a conceit or a decoration for valor. It is not a prize for being the most clever, the strongest, or the boldest. Glory belongs to the act of being constant to something greater than yourself, to a cause, to your principles, to the people on whom you rely, and who rely on you in return. No misfortune, no injury, no humiliation can destroy it.

Like Louis, I discovered in war that faith in myself proved to be the least formidable strength I possessed when confronting alone organized inhumanity on a greater scale than I had conceived possible. In prison, I learned that faith in myself alone, separate from other, more important allegiances, was ultimately no match for the cruelty that human beings could devise when they were entirely unencumbered by respect for the God-given dignity of man. This is the lesson many Americans, including Louis, learned in prison. It is, perhaps, the most important lesson we have ever learned.

Through war, and in peace, Louis Zamperini found his faith.

—October 2002

THAT TOUGH KID DOWN THE STREET

I

’ve always been called Lucky Louie.

It’s no mystery why. As a kid I made more than my share of trouble for my parents and the neighborhood, and mostly got away with it. At fifteen I turned my life around and became a championship runner; a few years later I went to the 1936 Olympics and at college was twice NCAA mile champion record holder that stood for years. In World War II my bomber crashed into the Pacific Ocean on, ironically, a rescue mission. I went missing and everyone thought I was dead. Instead, I drifted two thousand miles for forty-seven days on a raft, and after the Japanese rescued/captured me I endured more than two years of torture and humiliation, facing death more times than I care to remember. Somehow I made it home, and people called me a hero. I don’t know why. To me, heroes are guys with missing arms or legs—or lives—and the families they’ve left behind. All I did in the war was survive. My trouble reconciling the reality with the perception is partly why I slid into anger and alcoholism and almost lost my wife, family, and friends before I hit bottom, looked up—literally and figuratively—and found faith instead. A year later I returned to Japan, confronted my prison guards, now in a prison of their own, and forgave even the most sadistic. Back at home, I started an outreach camp program for boys as wayward as I had once been, or worse, and I

began to tell my story to anyone who would listen. I have never ceased to be amazed at the response. My mission then was the same as it is now: to inspire and help people by leading a life of good example, quiet strength, and perpetual influence.

I’ve always been called Lucky Louie. It’s no mystery why.

I WAS BORN

in Olean, New York, on January 26, 1917, the second of four children. My father, Anthony Zamperini, came from Verona, Italy. He grew up on beautiful Lake Garda, where as a youngster he did some landscaping for Admiral Dewey. My dad looked a little bit like Burt Lancaster, not as tall but built like a boxer. His parents died when he was thirteen, and soon after that he came to America and got a job working in the coal mines. At first he used a pick and shovel and breathed the black dust. Then he drove the big electric flatcars that towed coal out of the mines. He worked hard all his life, always had a job, always made money. But he wanted more, so he bought a set of books and educated himself in electrical engineering.

Anthony Zamperini wasn’t what you’d call a big intellect, but he was wise, and that’s more important. His wisdom sustained us.

My mother, Louise, was half-Austrian, half-Italian, and born in Pennsylvania. A handsome woman, of medium height and build, Mom was full of life, and a good storyteller. She liked to reminisce about the old days when my big brother, Pete, my little sisters, Virginia and Sylvia, and I were young. Of course, most mothers do. Her favorite stories—or maybe they were just so numerous—were about all the times I escaped serious injury or worse.

She’d begin with how, when I was two and Pete was four, we both came down with double pneumonia. The doctor in Olean (in upper-central New York State) told my parents, “You have to get your kids out of this cold climate to where the weather is warmer. Go to California so they don’t die.” We didn’t have much money, but my parents did not deliberate. My uncle Nick already lived in San Pedro, south of Los Angeles, and my parents decided to travel west.

At Grand Central Station my mother walked Pete and me along the platform and onto the train. But five minutes after rolling out, she

couldn’t find me anywhere. She searched all the cars and then did it again. Frantic, she demanded the conductor back up to New York, and she wouldn’t take no for an answer. That’s where they found me: waiting on the platform, saying in Italian, “I knew you’d come back. I knew you’d come back.”

MORE STORIES SHE

loved:

When we first moved to California we lived in Long Beach, but our house caught fire in the middle of the night. My dad grabbed me and Pete and whisked us out to the front lawn, where my mother waited. “There’s Pete,” she said, as my dad tried to catch his breath. “But where’s Louie?”

My dad pointed. “There’s Louie.”

“No! That’s a pillow.”

My dad rushed back into the burning house. His eyes and lungs filled with smoke, and he had to crawl on his knees to see and breathe. But he couldn’t find me—until he heard me choking. He crept into my room and spotted a hand sticking out from under the bed. Clutching me to his chest, he ran for the front door. While he was crossing the porch, the wood collapsed in flames and burned his legs, but he kept going and we were safe.

That wouldn’t be the last of my narrow escapes.

When I was three, my mother took me to the world’s largest saltwater pool, in Redondo Beach. She sat in the water, on the steps in the shallow end, chatting with a couple of lady friends while holding my hand so I couldn’t wander off. As she talked, I managed to sink. She turned and saw only bubbles on the surface. It took a while to work the water out of me.

A few months later a slightly older kid in the neighborhood challenged me to a race. I lived on a street with a

T

-shaped intersection, and the idea was to run to the corner, cross the street, and be first to touch a palm tree on the far side. He led all the way and was almost across the street by the time I got to the corner. That’s when the car hit him. I ran back home scared to death, pulled off a vent grate, and hid under the house. I could see the mangled boy lying on the con

crete, and the ambulance that soon took him away. I didn’t know his name; I don’t know if he died. I know it wasn’t my fault, but I’ve always felt guilty for taking up his challenge—and relieved that I lost my first race.

My mother would often remind me of those times, saying, “We move to California for your health, and here you are almost dying every day!”

MY DAD GOT

work as a bench machinist for the Pacific Electric Railroad, the company that ran the Big Red Cars, and we bought a house on Gramercy Street in Torrance, a neat little industrial town on what was then the outskirts of Los Angeles. There were still more fields than houses, and the barley rose three feet tall. At first, thinking we were renting, our German and English neighbors got up a petition against us. They didn’t want dagos or wops living on the street. But they had no choice. I still have a copy of the deed; it restricts the house from being sold to anyone other than “white Caucasians.” Although we qualified, the rule was still wrongheaded. My parents were hardworking, honest, and caring people forced into defending their rights and themselves. In the end they simply returned good for evil and just by being themselves won over the entire street. Twelve years later my brother and I were selected by the Torrance

Herald

as the “Favorite Sons of Torrance.” After World War II, when my parents were planning to move, the same neighbors who’d originally wanted to keep us out got up a petition to keep them from moving away.

My mother ran the household. She was strict but fair. Every morning before school we had chores. You’ve never seen a house as clean as an Italian home. She also cooked fabulous meals—lasagne, gnocchi, risotto—and we had a great family life. For as long as I can remember there was laughter in our home and the doors were always open to friends. After dinner we’d walk around the block and chat, then come back and play music. My mother played the violin, my dad the guitar and the mandolin. My uncle Louis, my mother’s brother, played every instrument there was. Dad would survey the gathering quietly and

break out with his gentle million-dollar smile. Everyone should have that kind of happiness.

When the Depression came my parents sacrificed all their comforts for the family. Dad made sure he paid our bills first and used whatever was left over for food and clothing. If we ran out of food, I’d shoot swamp ducks, mud hens, or wild rabbits for dinner. Or my mother would send us down to the beach at low tide to bring home abalone—the poor man’s meal in those days. Even though we didn’t have a lot of money, shopkeepers were extremely courteous because we were all in the same boat and everyone cooperated and helped one another. I don’t want another Depression, but we need some way today to help us all pull together again. A positive way.

I NEVER CONSIDERED

myself that different from my friends until I started grade school, where I began to feel painfully self-conscious. Everyone spoke English well but me. Now I can’t speak Italian, but then I got held back a year because I couldn’t understand the teacher. She called my parents and said, “You’ve got to start speaking English at home.”

We did, but only when someone insisted on it. Dad still considered Italian easier because he mispronounced a lot of English words or mixed up their meanings. Like, “Take the sweep and broom the sidewalk.” We knew what he meant, and he knew we knew, so there was no giving him a hard time.

My mother spoke better, and eventually I caught up with my English lessons and forgot most of my Italian, except for a few swear words. But I still had enough of an accent for the kids to pick on me. Though I was born in America, I was made to feel like an outsider. Every recess I was surrounded by jeering, kicking, punching, and rock-throwing kids. The idea was to make me crazy so I’d curse in Italian.

“Brutta bestia!”

The longer it went on the more my resentment grew.

It didn’t help that I thought I was a homely child with skinny legs, big ears, and a wild mass of black, wiry, hair. I could never get it to comb back and stay. I tried pomade, even olive oil. I’d wet down my

hair at night and stuff my head into a nylon or silk stocking with the foot cut off and the end tied. Because I spent so much time trying to get my hair to look like the other guys’, anybody at school who touched it was in trouble. Sometimes I didn’t wait to see who’d done it; I’d just turn and swing. Once I shoved a teacher. Another time I hit a girl with a glancing blow and the warning “You don’t mess up my hair!”

As a result I got beaten up a lot, and I wanted to kill those responsible. I spoke to my dad, and he made me a set of lead weights, got me a punching bag, and taught me to box. After about six months I got even by beating the hell out of those who bullied me. Once I followed a kid who taunted me into the bathroom; after landing a few punches I stuffed paper towels down his throat and left. Fortunately, another kid found him in time. When the principal heard, he sent me home and my dad punished me.

The whole time I was busy getting revenge I desperately wanted to fit in. For instance, I remember a mound of dirt on the school grounds and a big guy who’d get up there and say, “I’m king of the mountain!” I wanted in on that game; I wanted to be king of the hill, but he’d shove me down. One day my mother made an apple pie and gave me some for lunch at school. I gave it to the big guy. Finally he let me up on the hill.

Otherwise, my wish went unanswered. The group never really accepted me, and I had to follow my own path. More and more that became getting into trouble, and the self-esteem I developed from my successes there was the kind that comes from feeling good about getting away with being bad.

The wrong kind.

Take smoking. I had started when I was about five years old. At first it was curiosity; I got a little bit in my lungs and felt dizzy. But soon, walking to school each morning, I’d keep my eyes open for passing cars. If someone tossed a cigarette out the window, I’d run up, grab it, and save the butt until I had some matches.

Eventually the local motorcycle cop caught me. Afterward, whenever he could, he’d be at my house before school to give me a ride so I wouldn’t smoke.

When I was older, I’d wander in and out of stores and hotel lobbies with my head down, searching for butts. The long ones I saved for myself; the rest I dumped into a paper sack. Then I’d go to my favorite hiding place on Tree Row—a long, deep ditch by the railroad tracks, lined with eucalyptus—where I’d snip off the charred black ends, unravel the paper, and pour the loose tobacco into Prince Albert tins. This I sold to unsuspecting pipe smokers as “slightly used” tobacco for a nickel, half the retail price.

I tried chewing tobacco—in class. The teacher thought it was gum. “Louis, you spit that out immediately!” I swallowed instead and got sick as a dog.

Most Saturday nights my folks would bundle us kids into the backseat of their old car and drive to San Pedro, to shop at an Italian store. Then we’d visit relatives. I’d sniff the hard, black cigars left lying in the ashtrays and bide my time until I could empty a few wineglasses instead of drink the ginger ale set out for kids.

When I was in the third grade, the principal finally had enough. He put me over his knee and whacked me with the big strap that hung in his office. That afternoon, at home, my parents saw my purple, bruised behind when I changed clothes. “What happened to you, Toots!?” my mom asked, using her affectionate nickname.

“The principal beat me,” I said, like he was a stinker.

“What for?” asked my father.

“He caught me smoking.”

My dad very casually laid me over

his

knee, pulled down my pants, and spanked me on the same purple spot. I deserved it. I didn’t cry, though. I never cried. I didn’t stop smoking, either.

Soon, I had a reputation as “that tough little kid down the street.” I may have tried to look like an angel, but other parents warned me to stay on my own block and away from their children. I guess I played too rough. I cursed freely. I destroyed property. I ordered kids around. I never used my head, never thought about consequences.

In school, girls were informers who often told on me for my mischief. I had no use for them. But when I

wanted

their attention, I couldn’t get it. As revenge, I’d take whole cloves of garlic to the classroom and chew on them, then breathe in their direction just to offend

them. Some girls got so mad they struck or kicked me. In turn, I’d chase them and pull their hair.

I mostly hurt only myself. Once I fell and landed on a pipe. It punctured my thigh and took a big chunk out of my leg. Another time I jumped on a big piece of bamboo. It cracked and nearly cut off my toe, leaving it to dangle by a piece of skin. My mother held it in place while Mrs. Coburn, a nurse who lived next door, cleaned the wound and stitched it back on with a needle and thread. Then my mother taped it real tight, and miraculously it healed.