Devil-Devil

Authors: G.W. Kent

G. W. Kent

Title Page

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1: THE GLORY SHELL

2: THE GHOST-CALLER

3: THE DEATH CURSE

4: CUSTOM MAGIC

5: THE BONES TABU

6: LOFTY HERMAN

7: WHITE MAN’S WAYS

8: THAT’S WHERE ALL THE DANGER IS!

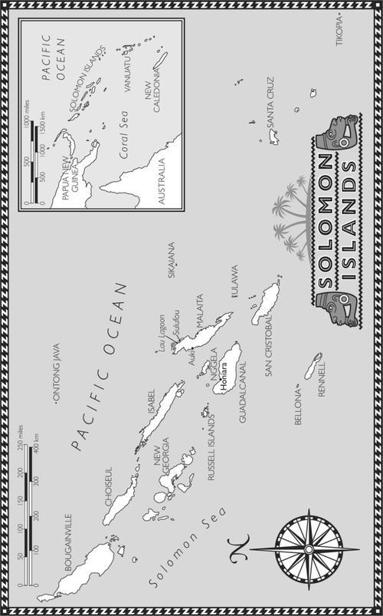

9: ARTIFICIAL ISLANDS

10: MANA

11: SIKAIANA WOMEN

12: COCONUT BOSS

13: PRAYING MARY

14: CAVE OF DEATH

15: PETER ORO

16: BEYOND THE REEF

17: MURDER TWICE OVER

18: THE CUSTOM WAY

19: CHINATOWN

20: LABOUR LINES

21: NIGHT TIDE

22: TRAILING SPEARS

23: BROTHER JOHN

24: THE STRAIGHT PATH CEREMONY

25: DISTRESSED BRITISH SUBJECT

26: HIGH BUSH

27: ROCKFALL

28: MARCHING RULE

29: GOLD RIDGE

30: THE CANARIUM TREE

31: CUSTOM SIGN

32: HUMILITY AND OBEDIENCE

33: PARAMOUNT CHIEFTAIN

34: DREAM-MAKER

35: KILLING GROUND

36: SERVICE MESSAGE

37: ONE SIMPLE AMBUSH

38: GRADUATION CEREMONY

About the Author

Copyright

I would like to thank Peter Noel Orudiana and Timothy Lopiga of the artificial island of Asimae in the Lau Lagoon of Malaita, guides and friends. I owe more than I can possibly say to my dedicated agent Isabel White, for her indomitable inspiration and determination. Thanks are also due to the charming and gifted editorial team at Constable & Robinson: Krystyna Green, Jo Stansall and Imogen Olsen, plus the sales, marketing and publicity departments, and all the team. I also owe a considerable debt of gratitude to everyone at my US publishers, SohoConstable, who have turned long-distance encouragement almost into an art form!

Sister Conchita clung to the sides of the small dugout canoe as the waves pounded over the frail vessel, soaking its two occupants. In front of her the Malaitan scooped his paddle into the water, trying to keep the craft on an even balance. Sister Conchita could see the coastal village a hundred yards away. The beach was crowded with islanders. She wondered whether it had been worth the perilous sea journey just to see the shark-calling ceremony when all she wanted was a shower and a meal. Of course it was, she told herself severely. If she intended serving God in the Solomons then she had to get to know everything about the islands.

The half-naked islander in front of her suddenly gave a scream of terror. Turning, he thrust the paddle into the sister’s hands and dived over the side of the canoe, disappearing into the frothing white foam. Sister Conchita sat rigid with apprehension, the pitted wooden blade clutched loosely in her hands. Bereft of the islander’s control, the canoe started pitching and swinging wildly.

For a moment all that Sister Conchita wanted to do was to cower helplessly in the bucking wooden frame. Then her customary resourcefulness took over. Snap out of it, she thought grimly. You got yourself into this hole, better get out of it the same way, girl. Muttering a fervent prayer, she tightened her grip on the paddle and thrust it with all her force into the water.

For the next five minutes the wiry young sister fought the sea. The momentum of the current was sending her at breakneck speed in the direction of the beach and the watching islanders, but the waves were crashing over the canoe at an angle, buffeting it from side to side. Several times the entire tree shell was submerged beneath the surface, but on each occasion it surfaced sufficiently for the sodden nun, coughing and gasping, to resume her paddling.

Doggedly she kept the prow of the canoe pointing at the beach. After an apparent eternity of choking, muscle-aching effort the shore actually seemed to be getting closer. One final shock of a wave descended on the canoe and hurled it sprawling up into the shallows off the beach.

Half a dozen brawny, cheering Melanesian men in skimpy loincloths splashed into the water and laughingly hauled the canoe up on to the sand. The crowd of assembled islanders broke into delighted applause. Dazedly Sister Conchita stood up and limped out of the beached craft.

Gradually her vision cleared. She blinked hard. Standing in front of her, joining vigorously in the acclamation among the large crowd, was the islander who had discarded his paddle and left her to fight the sea alone. Struggling for breath, Sister Conchita fought for the words adequately to express her opinion of him.

‘They’ve just been pulling your leg, sister,’ drawled a contemptuous voice from behind her. ‘They wanted to see what you were made of. You didn’t do so bad. Most sheilas just stay in the boat screaming bloody murder.’

The nun turned to see John Deacon, unshaven and clad in khaki shorts and shirt, regarding her coolly from the edge of the crowd.

‘Mr Deacon,’ said Sister Conchita, trying to keep her balance. Deacon was an Australian who managed a local copra plantation. She did not like him, suspecting him of ill-treating his labourers. However, she always tried, she suspected in vain, to conceal her feelings.

‘Local custom,’ explained the stocky, broad-shouldered

Australian

laconically. ‘Any stranger approaching the beach, the guide jumps overboard. Actually the current is bound to bring the canoe up on to the shore, but if you don’t know that, it can be a mite disconcerting.’

‘You can say that again,’ said Sister Conchita.

‘At least you had a go,’ acknowledged the plantation manager. ‘The natives like guts.’

‘Have you come for the ceremony?’ asked Sister Conchita politely, trying to change the subject. She did not wish to be reminded too much of her undignified arrival.

The Australian snorted with derision. ‘I don’t believe in superstition,’ he told her. His eyes scanned her tattered,

once-white

habit. ‘

Any

superstition,’ he told her with emphasis. ‘I’m here to pick up a cargo.’

Suddenly Deacon was swept aside by a phalanx of island women, offering the nun rough blankets with which to dry herself, together with a husk of coconut milk. In a chattering group they conducted her to a site at the water’s edge and waited eagerly with her. An artificial lagoon about twenty yards in diameter had been constructed there with piles of stones marking its edges, and an aperture on the seaward side to allow fish to swim in and out.

As the nun watched, an old man in tattered shorts and singlet emerged from one of the huts and walked down towards the stones. A profusion of ancient bone charms rattled on a string around his neck. A naked small boy of about ten years of age accompanied him.

‘

Fa’atabu

,’ muttered an awed woman. She translated for the nun’s benefit. ‘This one is the shark-caller,’ she said, indicating the old man.

Four islanders splashed out into the shallow waters of the shark area. They were carrying large flat stones, which they banged together under the water. Simultaneously the shark-caller started chanting in a high, tuneless voice. The crowd, which had swollen in numbers to several hundred, looked on in expectant silence.

For several minutes nothing happened. Then a reverent murmur went round the crowd. The fins of half a dozen sharks could be seen entering the enclosure.

The men, still clashing the stones together, fled from the water. Women picked up a few baskets of raw pork and placed them at the water’s edge before withdrawing hastily. Completely unperturbed, the boy hoisted one of the baskets up on to his shoulder and staggered out with it into the water, to a depth of several feet. To the accompaniment of screams and shouts from the crowd on the shore the sharks began to swim steadily towards the boy.

Sister Conchita found herself clenching her fists at the sight. The boy stood still for a moment. Then he reached up into the basket and started feeding the sharks lumps of raw meat, dropping these into the water just in front of him. As the sharks approached, accepting the food, the boy began to caress them. Throughout, the shark-caller continued his keening.

Sister Conchita looked on, fascinated by the sight. Out of the corner of her eye she became aware of Deacon and two Melanesians carrying a bulky sack along the ramshackle wooden jetty protruding into the sea. A dinghy was tethered there, bobbing in the water. Farther out to sea she could see the Australian’s trading vessel at anchor.

The sister did not want to leave the ceremony but she thought that it would only be courteous to say goodbye to the brusque plantation manager. Reluctantly she slipped through the crowd and made her way along the wharf. Deacon and his helpers were trying to load the sack into the heaving dinghy. The islanders were struggling to lower the sack to Deacon, waiting impatiently below. As she approached, one of the Melanesians dropped his end of the bulging sack. It burst open, disgorging a cascade of seashells.

Sister Conchita increased her pace to see if she could help. Some of the shells rolled across the wooden platform and nestled at her feet. The nun stooped to pick them up.

‘Leave that; we’ll sort it!’ ordered Deacon, scrambling up from the dinghy.

Sister Conchita ignored him. She had cradled three shells in her hands and was examining them with increasing excitement and anxiety. She would have recognized them anywhere. Before she had left Chicago she had attended a museum display of South Pacific seashells. The ones in her hands were a delicate golden brown in colour, with a round base tapering exquisitely to a point.

‘Are you deaf? I said I’ll take those!’ shouted Deacon, lumbering towards her.

Sister Conchita was intimidated by the Australian’s looming presence but stubbornly she clutched the beautiful shells to her.

‘I think not, Mr Deacon,’ she said, refusing to take a pace backwards, although every instinct warned her to get away from the plantation manager. ‘I believe these are glory shells,’ she went on. ‘You have no right to be taking them off the island. They’re a part of the culture of the Solomons.’

The

Conus

gloriamaris

, or Glory of the Seas, was the rarest of all seashells to be found in the Solomons, sought after in vain by almost every islander. It fetched over a thousand dollars among collectors. Its export was expressly forbidden by the government.