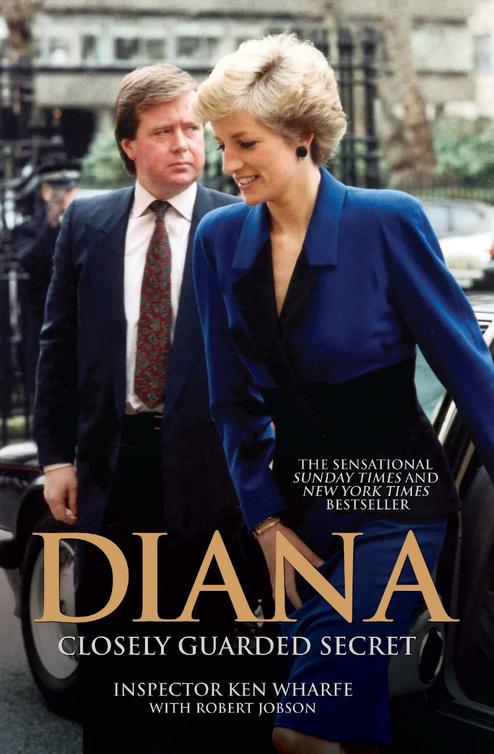

Diana--A Closely Guarded Secret

Read Diana--A Closely Guarded Secret Online

Authors: Ken Wharfe

T

he year 2017 will see the twentieth anniversary of Diana’s tragic death in Paris, an accident that could and should have been avoided. This memoir, first published in 2002, although a UK and USA bestseller, was not without its media detractors. Following her death in 1997 I later witnessed from my small office in St James’s Palace the rush to airbrush her memory. Spin doctors busied themselves paving the way for the acceptance of a woman about whom Diana was accused of being paranoid, while friends close to HM the Queen accused the late Princess of Wales of being ‘damaged goods’. The woman in question was Camilla Parker Bowles, now, as Duchess of Cornwall, the wife of Prince Charles.

Prince William and his brother Harry have since rescued their mother’s memory. She single-handedly worked to modernize the British monarchy, and to a considerable extent achieved

this thanks to her engaging, humorous personality and her commitment, a commitment her sons continue to display to this day.

I lecture regularly, often about Diana and my time as her personal protection officer, despite early attempts by my former employer, the Metropolitan Police, to halt the memoir. Prior to its publication some eighty books had been written about the Princess; many more have been published since. Yet

Diana: Closely Guarded Secret

continues to be regarded as an astute and accurate account of her life, despite the length of time since its first publication. In the words of the renowned historian David Starkey ‘This is history, since Ken Wharfe was there.’

K

EN

W

HARFE

,

MVO

July 2015

I

thought long and hard about writing this memoir of the late Diana, Princess of Wales. It was not a decision taken lightly but one I now firmly believe is correct if history is to judge her fairly.

But I could not have written this book without the dedication, wholehearted support and friendship of my co-writer, Robert Jobson, who believed, like me, that this story should be told.

Thanks also to my publisher, Michael O'Mara, for his guidance and forbearance but above all for believing in me and the project. I would also like to thank the editorial team at Michael O'Mara Books for their hard work, skill and enthusiasm, particularly my editor Toby Buchan, and Karen Dolan, Rhian McKay and Gabrielle Mander.

This book is written with all the men and women of Scotland Yard's Royalty Protection Department in mind. I would like to

thank all my friends and colleagues for the friendship and laughter we shared over the years, but above all for their dedication and professionalism which, I believe, cannot be equalled.

Â

I

NSPECTOR

K

EN

W

HARFE, MVO

August 2002

NO ONE COULD HAVE FAILED TO APPRECIATE the bitter irony of the day. For years I had been responsible for guarding this woman – with my life, if necessary. Now I was in charge of the police security operation for my department at her funeral. Standing, before the service, at the West Door of Westminster Abbey on Saturday, 6 September 1997, was like being a camera recording a scene in a tragic Hollywood movie. The difference, of course, was that this was painfully real. Everything seemed to be played out in slow motion. The organ resounded to William Harris’s

Prelude

; the bells rang out hollowly as the great and the good – from princes and prime ministers to so-called ordinary people – arrived to pay their last respects to an extraordinary person.

Diana, Princess of Wales had made the latter part of the twentieth century her own. In the last two decades of that

century, probably only Nelson Mandela approached her in terms of the interest she generated around the world. Now, after thirty-six years, her Camelot was in ruins and the magic, I was sure, would never return. I kept thinking to myself, ‘How on earth can this be happening?’ As the pallbearers – Welsh Guardsmen, as was fitting – struggled with her lead-lined coffin, it seemed almost inconceivable that the radiant young woman who had once charmed the world was lying silently within it, completely at peace for perhaps the only time in her all too short life. That life had been snuffed out by a combination of high spirits, stupidity and human error. That her death was avoidable made me angry, yet the whole sorry episode had numbed me inside, as it had most of the rest of the world. All I could think was, ‘What a waste, what a terrible, utter waste.’

Her sons, whom I had once guarded before I became her own personal protection officer, were nothing if not brave. She would have been supremely proud of the way they stood tall in the face of such terrible adversity. I had often played with them during their childhood. They had always loved to throw themselves into play fights; now they faced the greatest test of their lives. In their dark suits, focused in their grief, they looked like men, not boys, as they walked behind their mother’s coffin. On the flag-draped coffin a handwritten card lay among a cloud of lilies. On it, the single word ‘Mummy’ seemed to say everything.

A great calm fell over Central London that morning as millions took to the streets to pay their respects, lining the route along which the Princess’s coffin would be borne, on

a gun carriage, from Kensington Palace to the Abbey. As I walked to the Abbey from Buckingham Palace – with the roads closed, there was no other way of getting there – the scent of flowers was heavy on the air. Diana’s coffin had been moved from the Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace, where she had lain, to Kensington Palace at some time the previous evening. Everywhere her famous face peered out from the thousands of newspaper and magazine special editions being sold on the streets to mark the historic event. The nation had come to a complete halt as television coverage poured into millions of homes; around the world, more than two billion people sat and watched an event that many had believed they would not themselves live to see. At variance with the sombre mood, the mourners, many in jeans and T-shirts, were bathed in warm sunshine. Thousands upon thousands packed the funeral procession route as the muffled sound of the bells of Westminster Abbey, which tolled throughout the procession, carried mournfully over the near-silent capital.

Behind the coffin, the procession was led by her two sons, with the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, and her brother, Earl Spencer, heads bowed, walking with them. The tension was electric. As the gun-carriage passed on to the Mall, past Buckingham Palace, the Queen, who had been publicly attacked for her cool response since the death of the Princess, led other members of the royal family who, standing in front of the palace, all bowed as it passed. Above them, from the flagstaff on the Palace roof, the Union Flag fluttered at half-mast. The Queen had finally relented, after yet more criticism in the days before the funeral, and given the order for the flag

to be flown thus, the first time in history that it had done so for the death of anyone other than a monarch.

Behind Diana’s sons and her ex-husband, father-in-law and brother followed five hundred selected mourners. They were charity workers, nurses, artists, people from all walks of life representing organisations or causes that the Princess had held dear to her heart. Like so many people, I could not help thinking that this deviation from the practice usually followed at such state events was entirely in keeping with the spirit of my ex-boss, who in life had never greatly relished the pomp and circumstance surrounding royalty.

There were 1,900 invited guests within the spectacular Gothic interior of the Abbey. The sun streamed through its great windows. At just after ten o’clock the VIPs began to arrive. Shepherding them to their seats was like a military exercise, and my team had to be alert, not least because some of the world’s leading terrorist targets were gathered within this august medieval structure. America’s First Lady, Hillary Clinton – whose husband, President Bill Clinton, was one of countless world leaders who, only hours after her death, had publicly praised Diana and her life’s work – examined the tributes of flowers near the entrance as she walked past. Two former prime ministers, Baroness Thatcher and John Major, joined Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife, Cherie, on the long walk from the West Door to their seats in the Abbey.

Mohamed Fayed and his wife entered shortly after the Spencer family. My heart went out to them all, especially Diana’s mother, Frances Shand Kydd. Within the next few minutes the royal family arrived. Last, at 10.50 am, came the

Queen, the Queen Mother and Prince Edward. In deep silence they took their places near the altar, directly across the aisle from the Spencer family. Then, as the bells of Big Ben tolled eleven, the procession reached the West Door. Eight Welsh Guardsmen, bare-headed, their faces taut with strain, carried the quarter-ton coffin on their shoulders as they slow-marched the length of the nave. A profound hush fell over the Abbey. Prince Harry broke down when the coffin passed. As the tears flowed down his small face, his father pulled him closer and his brother William laid a comforting hand on his shoulder.

As the strains of the National Anthem filled the Abbey, the tension was excruciating, the Queen’s embarrassment almost palpable. The bitterness between the Spencers and the Windsors that had come to the fore in the days since the Princess’s fatal accident had given the national press something to write about, in a vain bid to try to divert the public’s attention away from the media’s involvement in the killing of

their

Princess. Yet such accusations were as pointless as they were wrong. The paparazzi may irritate like flies, but they don’t kill. Diana’s death, I kept thinking, was senseless because it could so easily have been prevented, but it was not photographers and journalists who killed her.

Nor was there any comfort in ‘if onlys’. My department had had the care of her for some fifteen years; Mohamed Fayed’s team of ‘bodyguards’ had had charge of her security for eight weeks, and now she was dead. They had failed in their task, and it angered me beyond words.

As I drifted between flashbacks and the awful reality of the moment, I kept saying to myself, ‘Come on, Ken, get on

with it.’ Lord Spencer had invited me to attend the funeral. I had declined, because I had been asked to look after security, although the job had not been easy. Mohamed Fayed had presented one of my first problems in this capacity. He had tried to insist that, in keeping with his bizarre conspiracy theories about the deaths of the Princess and his son Dodi, he was a target – even here. In the light of this, he said, he needed all his cumbersome, supposedly SAS-trained bodyguards by his side within the Abbey. This was a truly ridiculous idea, as though he outranked the Queen or the Prime Minister or the President of France, none of whom had personal bodyguards beside them. Before the funeral, I took some pleasure in reminding his ‘protection-liaison official’ of what I had said to his security staff when we reviewed security some days earlier, that no heavy protection presence would be permitted inside Westminster Abbey.

The ‘Libera Me’ from Verdi’s

Requiem

shook my resolve; not the soon-to-be-knighted Elton John’s specially written adaptation of ‘Candle In The Wind’, with its tear jerking first line, ‘Goodbye, England’s rose’, not even Diana’s favourite hymn, ‘I Vow To Thee, My Country’, which had been sung at her wedding. It was Verdi. Contrary to popular opinion, the Princess loved classical music, a passion we both shared. As the ‘Libera Me’ pierced the air and our souls, I felt the emotion of that piece engulf the Abbey, moving every one of the throng of mourners. Prince Charles looked as though he was being torn apart as the music swelled and dwindled, and finally died away.

Then, just as the congregation was united in grief, Lord Spencer unleashed his entirely unexpected verbal assault, his

words thrusting like a rapier into the Prince’s heart. No one, other than Charles Spencer, knew what was coming as he composed himself before delivering a five-minute eulogy that electrified the world. It was a piece of pure theatre, but it was also from the heart.

Spencer lashed out at the royal family for their behaviour towards his beloved sister, and savaged the press for hounding her to her death. Throughout the mauling the Queen bowed her head as her godson fired salvo after salvo, talking directly to his dead sister. ‘There is a temptation to rush to canonise your memory. There is no need to do so: you stand tall enough as a human being of unique qualities not to need to be seen as a saint.’ Nor, he said, was there any need for royal titles – a barbed reference to the Queen’s petty decision to remove from the Princess the courtesy title of ‘Her Royal Highness’ as one of the conditions of her lucrative $25.5 million (£17 million) divorce deal. He said bluntly that his sister had possessed a ‘natural nobility’, adding, cuttingly, that she transcended class and had proved in the last year of her life that ‘she needed no royal title to continue to generate her particular brand of magic.’ Never before, in forty-five years on the throne of Britain, had Queen Elizabeth II been publicly and savagely admonished by one of her subjects. Yet, ever the professional, she did not flinch.

What happened next was extraordinary, and something which only those inside the Abbey that day will ever fully appreciate. Lord Spencer’s loving yet devastating address was followed by a stunned silence. Then a sound like a distant shower of rain swept into the Abbey, seeping in through the walls, rolling on and on. It poured towards us like a wave,

gradually reaching a crescendo. At first I was not sure what it was; indeed, with security on my mind, I was momentarily troubled by it. It took me a couple of seconds to realise that it was the sound of people clapping. The massive crowds outside had heard Spencer’s address on loudspeakers and had reacted with applause; as the sound filtered in, the vast majority of the people inside the Abbey joined in. People don’t clap at funerals – but Diana was as different in death as she had been in life, and they did at hers. The Earl had spoken the plain truth as he saw it, and the people respected him for his courage as well as for the tribute he had paid his sister. William and Harry joined in the applause; so too, generously, did Prince Charles. The Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, and the Queen Mother sat unmoving in stony-faced silence.

The service ended with Sir John Tavener’s

Alleluia

. I found it uplifting, and at that moment my numbness lifted. The Princess was gone, but I knew that her spirit of compassion would live on, and that her work would not be forgotten.

Outside in the sunshine were millions of people, apparently united in grief. Yet though it may seem harsh or cynical, I felt that there was something spurious about the mass mourning that followed her death and attended her funeral. True, most people had loved her, but they had not known her. They loved the media image; they loved the glamour, the humanity, the sympathetic tears, but they had little idea of the real Diana. Mainly they loved her because of what they had read or seen or heard about her. What they were mourning was an image moulded by the media and, it must be said, by the Princess herself from her years in the public eye. Now the press was

being vilified. Yet surely, if the newspapers and photographers were to blame, in part, for her death, then the people must also share some of that blame? After all, they had bought the newspapers, pored over the magazines, read the books, sat glued to the television coverage. By another irony, some of them were clutching special Diana editions as they abused photographers who had gathered to record the funeral. As I looked at the hordes of people who had stood for hours to share this day and express their sorrow, I felt vaguely disturbed by it all. Despite her ego, her concern for her image, Diana would not really have wanted this.

Everywhere there were flowers, from single buds picked that morning to enormous bouquets – ‘floral tributes’, as florists (and undertakers) call them. She liked flowers; she would have liked the people’s thoughtful tribute. At Kensington Palace, where I had spent so many happy years, there had been a sea of flowers. They had begun arriving on the morning of the day she died, and now there was a field of them – literally, tons of flowers – outside the gates to Kensington Palace. The smell of them was almost overpowering. Luckily, someone had the sense to have them removed before they began to fade and rot, but still they kept coming.

England’s rose may be dead, I thought, as I walked back to my office near Buckingham Palace, but she had certainly made the world sit up and take notice while she was here. To me, she was a magical person, a woman of great character, strength, humour, generosity and determination, but she had needed to be channelled, her qualities guided in the right direction, her self-pity and her sometimes explosive temper checked. Some

of those around her played an important part in shaping the person who in death would come to be known as the People’s Princess, and who finally became, as she had once publicly hoped, the ‘queen of people’s hearts’.