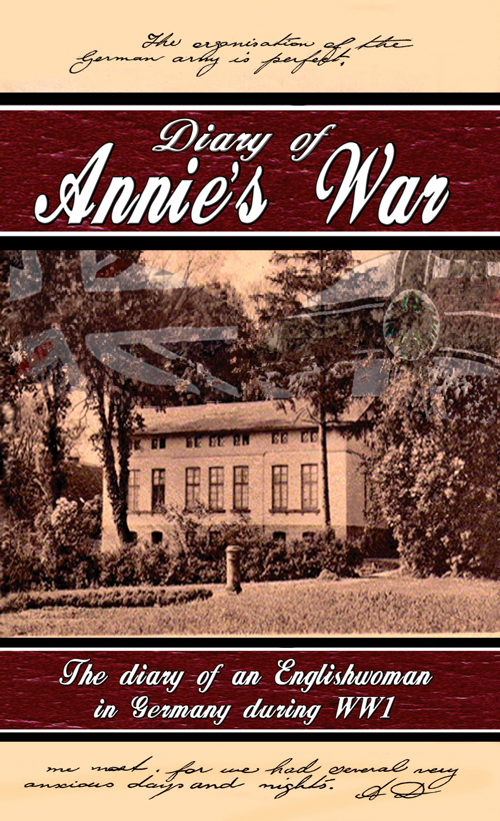

Diary of Annie's War

Read Diary of Annie's War Online

Authors: Annie Droege

In memory of the 16.5 million lives lost in the Great War - including 5.7 million Allied soldiers and four million troops with the Central Powers - it is estimated that 6.8 million civilians of all countries died. The figures are frightening, but the horror of modern warfare was even more terrifying for those caught up in the conflict that ran from 1914-1918.

Wilfred Owen 1893-1918.

Dulce et Decorum est pro patria mori (it is sweet and right to die for your country – sadly the Great War’s greatest poet did just that on November 4th 1918 seven days before the end of the conflict - his mother got the tragic news on Armistice Day):

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

GREAT Aunt Annie’s diary must have lain in the back of various cupboards for nearly a hundred years.

In 1940 the diary was rescued by her niece Jean Vlotman. On Aunt Jean’s death the diary was given to me. In its new home it gathered more dust until it was ‘rediscovered’ and fondly transcribed. Together with the diary was a small photograph album containing a few aged pictures - the only other remaining record of Annie and Arthur’s time in Germany.

There are many diaries from WW1 telling of the horrific times in the trenches but Annie Dröege’s diary describes the lives of the civilian German people living in and around the garrison town of Hildesheim and beyond during the Great War.

Annie Dröege tells of her time as the wife of a Ruhleben internee and of being a lone Englishwoman living in the land of her country’s enemy.

I have reproduced Annie’s handwritten account of her time in Germany to the best of my ability. I believe with the 100th anniversary of the start of the Great War approaching that it deserves a wider audience.

The diary is a well documented reflection of the social history and lives of the families in a German garrison town during the First World War. And I believe her work is of extra interest having been penned by an Englishwoman under virtual house arrest at times.

Mark Drummond Rigg.

ANNIE was born in the busy market town of Stockport on July 25th, 1874. She was the eldest of her parents Anne and John Drummond's nine children. On the early death of her mother she was left with the responsibility of looking after her seven remaining brothers and sisters, aged from five to twenty, and her father.

The family was reasonably well-to-do as John worked for his mother another Annie â known as âThe Duchess of Lever Street' - at her millinery business in Manchester. Annie's grandmother exported smocks, hats, and bonnets to Germany using the local Commission Agents Dröege & Co.

Through her grandmother's business Annie first met the love of her life Arthur - the younger son of German Leopold Dröege and his English wife Elizabeth. Arthur Dröege was a British national and had been educated in England. Arthur was a leading light in the family business and befitting his position he spoke six languages fluently.

After meeting in their youth a romance blossomed and after a serious courtship Annie and Arthur wed on the 30th June 1900 at St Philip and St James' Church in Shaw Heath, Stockport, Cheshire.

In the March of 1902 their daughter Annie Josephine was born. Sadly, baby Annie Josephine died in December 1903 and then to add more heartache their son Leopold died shortly after his birth.

Arthur's father Leopold died in March 1908 and the following year Arthur's older brother Marcus died at the age of 29. This bereavement was quickly followed by another back in Germany of Arthur's uncle, a friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who died without issue.

Following his father's death Arthur changed careers and became a foreign correspondent working from his home in Stockport for the German press.

And after his uncle's demise, as the oldest living male relative, Arthur inherited his relative's possessions. These included a manor and vast estate in the village of Woltershausen, Lower Saxony, where the lands were let to tenant farmers. He was also heir to a house in Hildesheim, a villa by the Rhine in Königswinter and a house by the health springs in Bad Salzdetfurth.

On their arrival in Woltershausen Arthur was welcomed as the new owner and the inheritance appeared to be a fantastic opportunity. Annie was surprised and disappointed to find that the German domestic staff, though naturally polite, only regarded her as âthe Frau of Herr Dröege'.

Annie worked on her strengths and as âthe Frau of Herr Dröege' found that she could be a valuable mediator between the tenant farmers, their wives and her husband.

All was settled and uneventful until the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914.

In early November of that year Arthur was taken to Ruhleben as a German prisoner-of-war. This came about after England had refused to release prisoners of German nationality. The reason given for his imprisonment was that Arthur had an English mother. Annie, whilst expecting imprisonment, was ordered to report to the police twice daily. She was left alone to look after Arthur's affairs.

Now known as âThe Outlander' Annie was shunned by many old friends and others who knew she was English.

Many times she did have the option of returning to England but said repeatedly: âWhen we leave, we leave together'.

This is her story, in her own words.

th

â 1914

It was a suggestion of Belle van der Busch that we should take notes of these anxious days. I, especially, having plenty of time.

Though it is now sixteen weeks since the war began I think the most important events to me will easily come back to memory. So, as near as possible, I will give the dates of the events which concerned me much, for we had several very anxious days and nights.

A.D.

The diary of Annie Dröege.

Germany WW1.

th

July 1914.

Emily Durselen came to visit us - bringing with her, from England, Winnie Crocker and also Marjorie Henson. The two children were to stay six weeks and return in time for school on September 12

th

. James Walmsley, from Blackpool, had been with us a short time and we were a merry party for a few days.

The first we heard of the war, to take it seriously, was a letter to Emily D. from her sister, Frau Graeinghoff, of Königswinter, in which she regretted Emily and the children had come. We laughed very much at the idea because they had only been with us four days. The letter came on the Thursday morning and when the newspaper came in the afternoon Arthur thought it probable that Russia and Germany might go to war. But we were so merry we forgot all about it in a few minutes.

st

July.

Arthur, James and I went into Hildesheim. There we heard that all preparations were in hand and everyone was talking of the war. To fight Serbia and Russia meant nothing to them. So they said. If only England would keep out of it. They said they could not trust her, she was so sly.

When we got to Harbarnsen in the evening we met some of the men of our village already going away. Still James and Arthur had no fear for they were sure England would not join. They did not see how it could affect us.

nd

August 1914.

When we were at church at Lamspringe we found the reserves had been called up, officers especially, at a few hours notice. We were left without a medical doctor and a vet surgeon. Dr. Foss was a marine officer and Dr. Kort was a field officer. It was something serious for us for they had to attend to seven or eight villages. They had to go quickly. What surprised me even then was that England was blamed for it all.

After church Arthur and James decided to go to Hildesheim and enquire if it was possible for James to leave. The trains were all being used for the transport of soldiers and we were afraid he would have difficulty in getting direct to Hamburg. They could get no definite news so Arthur telephoned from Hildesheim to the shipping office and heard that a boat would sail on Tuesday 4

th

August. It was decided to try for that. I posted three letters on this date to England.

rd

August.

James, Arthur and I were in Hildesheim. I shall never forget it. I saw there the crowds of young men called up to military duty. We could scarcely get any news of the trains. None of the officials knew anything. All trains being held up for transport of horses and men. At last we heard that a train was likely to go sometime after dinner and I left Arthur and James at the hotel about half past two. I went to do a little shopping and they were to go to the station.

I was very doubtful of James getting away for already the people were saying strange things about England. Arthur was doubtful also but said it was James' wish to try his luck. I called on Belle v.d. Busch and she told me that her husband's mother died on the 28

th

July and was buried on the 30

th

. Her eldest son, who is an officer, could not remain for the funeral being called away to the front the same morning.

The organisation of the German army is perfect. The vet from Lamspringe wrote that, although called up in a few hours notice, every man's outfit and every horse's harness was quite complete. Each man was fitted up in a few minutes and every buckle in its place on the harness. The shoemaker from our village said he was at once put to his trade in the barracks. They turned out three thousand pairs of shoes a day. The butcher also was called and he was kept busy at his trade. The supply of men was wonderful. Each train that came in was crowded with men. There was a man on each platform who directed them to their respective barracks and one saw no confusion at all.

After the regular army had gone away (many thousands) there came the âfree willing' which consisted of men over thirty years old and men under twenty years old. Those under twenty had to drill and these over thirty only needed a couple of weeks and then they were ready. So many came that they could not accept them all and many thousands were told to present themselves again in a month.

When we returned home on the Monday evening after seeing James on his journey to Hamburg we found a notice saying that Arthur must take the horse, âMoor', to Alfeld on the Thursday August 6

th

. We had already had warning that he must be in readiness the Saturday before.

th

August.

The day found us very anxiously awaiting the reply from England. At noon we got a card from James saying that he got to Hamburg all right and hoped to sail on Tuesday. He told us that the ship that sailed on the Saturday had been turned back. When Arthur heard that he said James would not sail until England had answered Germany. If the answer was unfavourable the ship would not sail at all. We were very miserable that night for the uncertainty was dreadful and the people were saying awful things about England.

th

August.

We drove to Lamspringe, Arthur and I alone, for there was a special Mass at six o'clock in the morning for the soldiers at the front. As we drove through the villages of Graste and Netze I remarked to Arthur the unwillingness of the men to open the barriers which were across the roads at the entrance to every village. These barriers had been put up the first day of the war and at each was a man, sometimes two men, with a loaded gun. Their duty was to examine every strange cart or person who came along. If they knew you they often had the barrier open as you got to them. This morning however they made us pull up the horse and then slowly undid the barrier.

Going into Lamspringe there were quite a lot of men and they let us wait a few seconds before they let us pass. Arthur thanked them but they made no reply. I felt nervous for we had to go the same way back. When I looked at Arthur I was surprised to see how pale he had gone. I think we both feared war with England had been declared. But we never mentioned it to each other.