Did Muhammad Exist?: An Inquiry into Islam's Obscure Origins (2 page)

Read Did Muhammad Exist?: An Inquiry into Islam's Obscure Origins Online

Authors: Robert Spencer

654: Arabian conquest of Cyprus and Rhodes

656–661:

Caliphate of Ali

661–680: Caliphate of Muawiya

660s/670s: Coin depicts Muawiya holding a cross topped with a crescent

660s/670s: Armenian bishop Sebeos writes a semihistorical, semilegendary account of Mahmet, an Arab preacher who taught his people to worship the God of Abraham and who led twelve thousand Jews, along with Arabs, to invade Palestine

662: Bathhouse in Palestine is dedicated with an official inscription that mentions Muawiya and bears a cross

674: First Arabian siege of Constantinople

680: Anonymous chronicler identifies Muhammad as leader of the “sons of Ishmael,” whom God sent against the Persians “like the sand of the sea-shores”

680–683: Caliphate of Yazid I

Early 680s: Coins apparently depicting Yazid feature a cross

685: Abdullah ibn Az-Zubair, rebel ruler of Arabia, Iraq, and Iran, mints coins proclaiming Muhammad as prophet of Allah

685–705: Caliphate of Abd al-Malik

690: Nestorian Christian chronicler John bar Penkaye writes of Muhammad's authority and the Arabians' brutality

690s: Coptic Christian bishop John of Nikiou makes first extant mention of “Muslims” (although the earliest available edition of his work dates from 1602 and may have been altered in translation)

691: Dome of the Rock inscription declares that “Muhammad is the servant of God and His messenger” and that “the Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was only a messenger of God,” and features an amalgamation of Qur'an quotes

696: First coins appear that do not feature an image of the sovereign and do feature the Islamic confession of faith

(shahada)

690s: According to a variant Islamic tradition, Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, governor of Iraq, collects the Qur'an, standardizes its text, has variants burned, and distributes his version to all the Islamic provinces

690s: Hajjaj ibn Yusuf introduces into mosque worship the practice of reading from the Qur'an, according to a later Islamic tradition

690s: Hajjaj ibn Yusuf adds diacritical marks to text of the Qur'an, enabling the reader to distinguish between various Arabic consonants and thereby make sense of the text

711–718: Muslim conquest of Spain

730: Christian writer John of Damascus refers to Islamic theology in detail, and to suras of the Qur'an, although not to the Qur'an by name

732: Muslim advance into western Europe is stopped at the Battle of Tours

750s–760s: Malik ibn Anas compiles the first Hadith collection circa 760 Ibn Ishaq collects biographical material and publishes first biography of Muhammad

830s–860s: The six major Hadith collections are compiled and published, providing voluminous detail about Muhammad's words and deeds

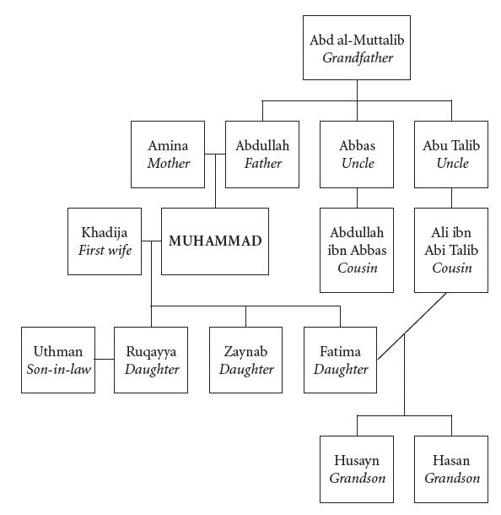

Muhammad was the son of Abdullah and Amina.

Muhammad's paternal grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, had a son, Abbas. His son, Abdullah ibn Abbas, was Muhammad's cousin. Many hadiths are attributed to Abdullah ibn Abbas as the ultimate source: The chain of transmitters begins with him as the witness of the event recounted.

Abdullah's brother Abu Talib was Muhammad's guardian after the deaths of Abdullah and Amina. He was also the father of Ali ibn Abi Talib, who was Muhammad's cousin and the founding figure of Shiite Islam.

Muhammad and his first wife, Khadija, had three daughters: Fatima, Zaynab, and Ruqayya.

Fatima married Ali ibn Abi Talib and had five children, including the Shiite heroes Hasan and Husayn. The latter was killed in the Battle of Karbala in 680, which sealed the split between the Sunnis and the Shiites.

Ruqayya married Uthman, who became the third caliph after Abu Bakr and Umar.

Ali succeeded to the caliphate when Uthman was murdered. When Ali was murdered, Muawiya, Uthman's cousin, became caliph.

Introduction

In place of the mystery under which the other religions have covered their origins, [Islam] was born in the full light of history; its roots are on the surface. The life of its founder is as well known to us as that of any sixteenth-century reformer. We can follow year by year the fluctuations of his thought, his contradictions, his weaknesses.

—Ernest Renan, “Muhammad and the Origins of Islam” (1851)

Shadows and Light

D

id Muhammad exist?

It is a question that few have thought to ask, or dared to ask.

For most of the fourteen hundred years since the prophet of Islam is thought to have walked the earth, almost everyone has taken his existence for granted. After all, his imprint on human history is enormous.

The

Encyclopedia Britannica

dubbed him “the most successful of all Prophets and religious personalities.” In his 1978 book

The 100:

A

Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History

, historian Michael H. Hart put Muhammad in the top spot, explaining: “My choice of Muhammad to lead the list of the world's most influential persons

may surprise some readers and may be questioned by others, but he was the only man in history who was supremely successful on both the religious and secular level.”

1

Other historians have noted the extraordinarily rapid growth of the Arabian Empire in the period immediately following Muhammad's death. The Arabian conquerors, evidently inspired by his teaching, created an empire that in fewer than one hundred years stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to India. Not only was that empire immense, but its cultural influence—also founded on Muhammad's teaching—has been enduring as well.

Moreover, Islamic literature contains an astounding proliferation of biographical material about Muhammad. In his definitive two-volume English-language biography of Muhammad,

Muhammad at Mecca

(1953) and

Muhammad at Medina

(1956), the English historian W. Montgomery Watt argues that the sheer detail contained in the Islamic records of Muhammad, plus the negative features of his biography, make his story plausible.

2

However sharply people may differ on the virtues and vices of Muhammad, and on the value of his prophetic claims, virtually no one doubts that he was an actual person who lived in a particular time and a particular place and who, more to the point, founded one of the world's major religions.

Could such a man have never existed at all? There is, in fact, considerable reason to question the historicity of Muhammad. Although the story of Muhammad, the Qur'an, and early Islam is widely accepted, on close examination the particulars of the story prove elusive. The more one looks at the origins of Islam, the less one sees.

This book explores the questions that a small group of pioneering scholars has raised about the historical authenticity of the standard account of Muhammad's life and prophetic career. A thorough review of the historical records provides startling indications that much, if not all, of what we know about Muhammad is legend, not historical fact. A careful investigation similarly suggests that the Qur'an is not a

collection of what Muhammad presented as revelations from the one true God but was actually constructed from already existing material, mostly from the Jewish and Christian traditions.

The nineteenth-century scholar Ernest Renan confidently claimed that Islam emerged in the “full light of history.” But in truth, the real story of Muhammad, the Qur'an, and early Islam lies deep in the shadows. It is time to bring it into the light.

Historical Scrutiny

Why embark on such an inquiry?

Religious faith, any religious faith, is something that people hold very deeply. In this case, many Muslims would regard the very idea of applying historical scrutiny to the traditional account of Islam's origins as an affront. Such an inquiry raises questions about the foundational assumptions of a belief system that guides more than a billion people worldwide.

But the questions in this book are not intended as any kind of attack on Muslims. Rather, they are presented as an attempt to make sense of the available data, comparing the traditional account of Islam's origins against what can be known from the historical record.

Islam is a faith rooted in history. It makes historical claims. Muhammad is supposed to have lived at a certain time and preached certain doctrines that he said God had delivered to him. The veracity of those claims is open, to a certain extent, to historical analysis. Whether Muhammad really received messages from the angel Gabriel may be a faith judgment, but whether he lived at all is a historical one.

Islam is not unique in staking out its claims as a historical faith or in inviting historical investigation. But it is unique in

not

having undergone searching historical criticism on any significant scale. Both Judaism and Christianity have been the subject of widespread scholarly investigation for more than two centuries.

The nineteenth-century biblical scholar Julius Wellhausen's

Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (Prolegomena to the History of Israel)

, a textual and historical analysis of the Torah, revolutionized the way many Jews and Christians looked at the origins of their scriptures and religious traditions. By the time Wellhausen published his study in 1882, historical criticism, or higher criticism, of Judaism and Christianity had been going on for more than a hundred years.

The scholarly “quest for the historical Jesus” had begun in the eighteenth century, but it was in the nineteenth century that this higher criticism took off. The German theologian David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874) posited in his

Das Leben Jesu, kritisch bearbeitet (The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined)

(1835) that the miracles in the Gospels were actually natural events that those anxious to believe had seen as miracles. Ernest Renan (1823–1892) in his

Vie de Jésus (The Life of Jesus)

(1863) argued that the life of Jesus, like that of any other man, ought to be open to historical and critical scrutiny. Later scholars such as Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) cast strong doubt on the historical value of the Gospels. Some scholars asserted that the canonical Gospels of the New Testament were products of the second Christian century and therefore of scant historical value. Others suggested that Jesus of Nazareth had never even existed.

3

Eventually, higher critics who dated the Gospels to the second century became a minority of scholars. The consensus that emerged dated the Gospels to within forty to sixty years of the death of Jesus Christ. From that gap between the life of their protagonist and their publication, many scholars concluded that the Gospels were overgrown with legendary material. They began trying to sift through the available evidence in order to determine who Jesus was and what he really said and did.

The reaction within the Christian world was mixed. Many Christians dismissed the higher criticism as an attempt to undermine their faith. Some criticized it for excessive skepticism and one-sidedness, regarding historical-critical investigations of the Gospels and the historicity of Christ as the critics' effort to justify their own

unbelief. But others were more receptive. Large Protestant churches such as the Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Methodists ultimately abandoned Christian dogma as it had hitherto been understood, espousing a vague, nondogmatic Christianity that concentrated on charitable work rather than doctrinal rigor and spirituality. Other Protestant denominations (including splinters of the three named above) retreated into fundamentalism, which in its original formulation was a defiant assertion, in the face of the higher critical challenge, of the historicity of the Virgin Birth of Christ, his Resurrection, and more.

Pope Leo XIII condemned the higher criticism in his 1893 encyclical

Providentissimus Deus

, but nine years later he established the Pontifical Biblical Commission, which was to use the tools of higher criticism to explore the scriptures within a context respectful to Catholic faith. In 1943 Pope Pius XII encouraged higher critical study in his encyclical

Divino Afflante Spiritu.

The Catholic Church ultimately determined that because its faith was historical, historical study could not be an enemy of faith, provided that such investigations did not simply provide a cover for radical skepticism.