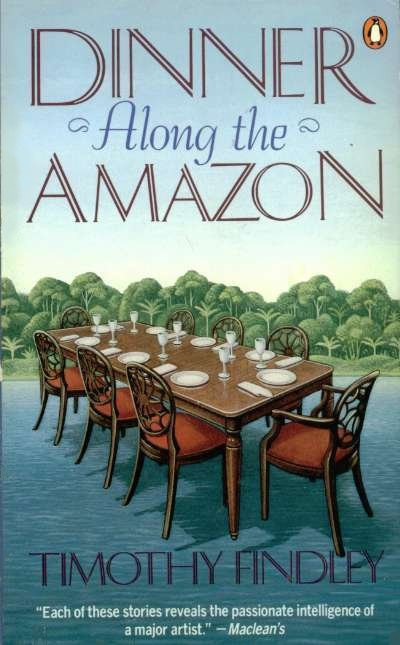

Dinner Along the Amazon

Read Dinner Along the Amazon Online

Authors: Timothy Findley

DINNER

ALONG THE

AMAZON

Timothy Findley

First published by

Penguin Canada

1984

The sound of screen doors banging, evening lamplight; Colt revolvers hidden in bureau drawers and a chair that is always falling over.

These are the sounds and images that illuminate this brilliant collection of twelve short stories from one of Canada’s finest writers.

The stories range from the powerful, haunting

Lemonade

, where a young boy’s world is shattered by his mother’s self destruction, to the title story, an unusual journey into the complexities of modern relationships, written especially for this collection.

“Thanks to this volume, some of the best of Findley’s stories are now spread glitteringly before us. His accomplishments in this exacting art are as proportionately large as his novels, as solid as they are brilliant”

—

Toronto Star

“Each of its stories reveals the passionate intelligence of a major artist…

Dinner Along the Amazon

displays a rare gentleness in Findley’s chronicles of suffering. He portrays guilt and misery with such luminous understanding that even his most disturbing stories rarely seem depressing.”

—

Macleans

“…in this astounding

Dinner Along the Amazon

, Timothy Findley restores an almost forgotten power to the art of fiction: the creation of a deep, coherent world in which we see our own.”

—

Books in Cancan

DINNER ALONG THE AMAZON

Timothy Findley was born in Toronto and now lives in the country nearby. His novel,

The Wars

, was a winner of the Governor-General’s Award and a winner of the City of Toronto Book Award, establishing him as one of Canada’s leading writers. The book was acclaimed throughout the English-speaking world and has already appeared in eight translated editions. Findley wrote the screenplay for the film,

The Wars

, directed by Robin Phillips.

Famous Last Words

, his bestselling novel of gripping international intrigue, was published in 1981 to rave reviews, and in 1983 Penguin reissued

The Last of the Crazy People

, his brilliant first novel.

For

Marian Engel

We will sit in a circle longing for the lights of Moscow. We will bite each other’s fingers, to see the blood. We will continue to clean our houses. We will make artifacts.

And the morning will come, and so will the night again. Won’t it?

The Honeyman Festival

Marian Engel

“Not that the story need be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.”

—Henry David Thoreau

Acknowledgements

“Lemonade” first appeared in

Exile

, in a slightly different form and titled “Harper’s Bazaar.”

“War” was read on CBC’s “Anthology.”

“About Effie” first appeared in

The Tamarack Review

, Autumn, 1956.

“Sometime - Later - Not Now” first appeared in

The New Orleans Review

, 1972.

“What Mrs Felton Knew” first appeared in

Cavalier

, April, 1970, under the title “E.R.A.”

“The People on the Shore” was read on CBC’s “Anthology.”

“Hello Cheeverland, Goodbye” first appeared in

The Tamarack Review

, November, 1974, in a somewhat different form.

“Losers, Finders, Strangers at the Door” first appeared in 75:

New Canadian Stories

, 1975, Oberon Press.

“The Book of Pins” first appeared in 74:

New Canadian Stories

, 1974, Oberon Press.

“Daybreak at Pisa” first appeared in

The Tamarack Review

, Winter, 1982.

“Out of the Silence” first appeared in

Ethos

, Summer, 1983.

Contents

Losers, Finders, Strangers at the Door

Introduction

It came as something of a shock, when gathering these stories for collective publication, to discover that for over thirty years of writing my attention has turned again and again to the same unvarying gamut of sounds and images. They not only turn up here in this present book, but in my novels, too. I wish I hadn’t noticed this. In fact, it became an embarrassment and I began to wonder if I should file

A CATALOGUE OF PERSONAL OBSESSIONS

. The sound of screen doors banging; evening lamplight; music held at a distance—always being played on a gramophone; letters written on blue-tinted note paper; robins making forays onto summer lawns to murder worms; photographs in cardboard boxes; Colt revolvers hidden in bureau drawers and a chair that is always falling over. What does it mean? Does it mean that here is a writer who is hopelessly uninventive? Appallingly repetitive? Why are the roads always dusty in this man’s work—why is it always so hot—why can’t it

RAIN

? And my agent was once heard to moan aloud as she was reading through the pages of a television script I had just delivered: “Oh God, Findley—

not more rabbits!

”

Well. Yes…

More rabbits; more dusty roads. I’m sorry, but I can’t help it. I seem to be stuck with these obsessions and perhaps they simply go hand in hand with those other obsessions all writers have: the kinds of men and women they write about; the way they bring their people together and tear them apart; what sort of names they give their characters and whether they give them cats or dogs to live with. Or rabbits. More than likely, it is these obsessions which signal, as much as anything else, whose world you are in. In the world of Alice Munro, for instance, there tend to be a number of visiting aunts or aunts in residence or aunts “

we’re just going to drop by and see

.” In Chekhov’s gallery there are all those wonderful portraits of the doctor who fails his calling and who makes a profession of disillusionment. In Maugham, there is always Maugham—the perfect narrator, hovering at the story’s edges but never in the story’s way, (obsessed with being there—and nothing more). In Cheever there is always infidelity, which is always futile, always sad—always a part of the growing up process, the inevitable discovery that youth is not a gift for life. And yet, we never tire of Munrovian aunts, Chekhovian doctors, Maughamish Maughams or of Cheever’s wistful losers. Why? It strikes me the answer must be that we never tire of them precisely because the writer never tires of them, but finds them always freshly seething with possibilities whenever another aunt, another doctor or another man in love with his neighbour’s wife hoves into view.

When you come right down to it, the pursuit of an obsession through the act of writing is not so much a question of repetition as it is of regeneration. Each of Chekhov’s doctors begets another, whose tics may be reminiscent of his forebear, but whose person and condition are quite, quite different. And the regeneration surely is a sign, a signal that something remains to be done with this person, that the writer instinctively recognizes everything hasn’t been said about him: all the questions have not been put, including the most important question of all: why am I obsessed with you? One day this question—all the questions—may be answered and when this happens, the character disappears. No more disillusioned doctors. This is What happened with Chekhov. All those doctors in his stories—and in every full length play but one—his last,

The Cherry Orchard

. This suggests there may be hope—that all your obsessions do not track you to the grave.

On the other hand, writers are never through with the world they see and hear. Even in the silence of a darkened room, they see it and they hear it, because it is a world inside their heads, which is the “real” world they write about. Of course, this interior world is fed by the world we all share—the one we all move around in every day of our lives. But the writer tends to feed it selectively—a little of this, a little of that; none of some things and a lot of others. This process of feeding the world inside your head goes on from the moment you are first aware there are not only things to see and things to touch and things to hear—but also things to record. Don’t ask why. There isn’t any reason. It is simply something required of a person, the way you are required to go to bed at night and get up in the morning. Your body—or something in your body demands it: an obsession like any other.

The stories in this book are arranged chronologically, by decades. “Lemonade” (which was published as “Harper’s Bazaar”) got started in a flat which I shared with the actor, Alec McCowen, and was completed in an old hotel where I shared rooms with an actress, Sheila Keddy. Later, it was altered and finalized on the dining room table in the home of my agents, Stanley and Nancy Colbert. I don’t know how it has any unity at all, since my flat with Alec was in London, England and the old hotel where I lived with Sheila was in Washington, D.C. and the Colberts’ dining room table was in Hollywood, California. Needless to say, I was glad when I finally settled down.

Some of these stories, or incidents within them, are drawn from real life—either my own or the lives of others. This has no real importance, it seems to me, since all of the people would fail to recognize themselves—even Ezra and Dorothy Pound or Tom and Vivienne Eliot, who appear towards the end of the book. It was simply that something about them—about these real people—something overheard or spotted from the corner of my eye, caught at my attention and worried me until I had it on the page. The Eliot story is the best example of this. It is fairly safe to say that no such confrontation as the one depicted in “Out of the Silence” ever took place—and if it did, it more than likely only took place in Vivienne Eliot’s mind. What caught me—the thing with which I became obsessed—was the thought that two people could live together for so long, endure the same history and the same painful experience of marriage, and yet the same history and experience could produce madness in one of them and poetry in the other. It was also intriguing to me that Eliot had put so much of Vivienne into that poetry—that he had even put her there before he met her, before he knew her and married her. It was as if he had willed a fictional lady with whom he was obsessed to come all the way into real life. And what could that mean…?

This provides the perfect place for me to invite you into this book, and into the world with which I have been obsessed for so long.

Lemonade

For Ruth Gordon

Every morning at seven o’clock Harper Dewey turned over and woke up. And every morning he would lie in his tumbled bed (for he slept without repose even at the age of eight) until it was seven-thirty, thinking his way back into his dreams, which were always of his father. At seven-thirty he would get out of bed and cross to his window where he would stand for a moment watching his dreams fade in the sunlight until there was nothing in the garden save the lilac and the high board fence.

And the birds.

Robins and starlings and sparrows flowed over the smooth lawn in great droves, turning it into the likeness of a marketplace; and the raucous babble of their bargaining (of dealings in worms and beetles and flies) poured itself, like something distilled or dehydrated, from the jar of darkness into the morning air, which made it swell and burst. This enormous shout of birds at morning was always a delight to Harper Dewey.

Presently, over this sound, there would burst the first indication of an awakening household: Bertha Millroy’s hymn.

Bertha Millroy was the maid—and a day, to Bertha, wasn’t a day at all unless it began with a hymn and ended with a prayer.

She lived—Bertha—in the attic, in a small room directly above Harper’s room and she sang her hymn from the window which opened over his head. When it was finished she would say the same thing every morning—“Amen” and “Good morning Harper.” Then they would race each other to the landing on the stairs. Harper never cheated, although he could easily have been dressed long before Bertha if he had chosen to be, because he was always awake so much earlier than her. But this every morning race had never been specifically agreed upon and if Harper had ever said to Bertha at the window “Let’s race,” or if Bertha had ever said to Harper below her “Beat you downstairs,” the whole procedure would have been off. Neither of them could remember when this habit had started—it just had.

Well, one morning early in the summer, (in fact it was hardly more than late spring), Harper and Bertha met on the stairs’ landing—Bertha won—and after they had scanned the note they found there, they looked at each other and then quickly looked away. They descended to the first floor in their usual fashion—Harper going down the front stairs to collect the paper from the front porch—and Bertha going down the back stairs to light the stove and to bring in the milk.

This morning, Harper didn’t open the paper, although he usually read the comics sitting on the porch step. Instead he returned inside, letting the screen door clap behind him and leaving the big oak and glass door open so that the air could come through, into the still house. He went straight out to the kitchen and sat down at the table, slipping the still folded paper onto the breakfast tray which was laid out for his mother.