Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great's Empire (40 page)

Read Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great's Empire Online

Authors: Robin Waterfield

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #General, #Military, #Social History

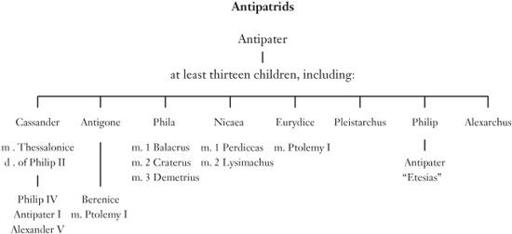

Thessalonice:

half sister of Alexander III; captured and subsequently married by Cassander in 316; failed to keep the peace between Antipater I and Alexander V; murdered by Antipater.

Zipoetes

of Bithynia (327–280): ruler of independent Bithynia; subdued by Antigonus but resurgent after Ipsus.

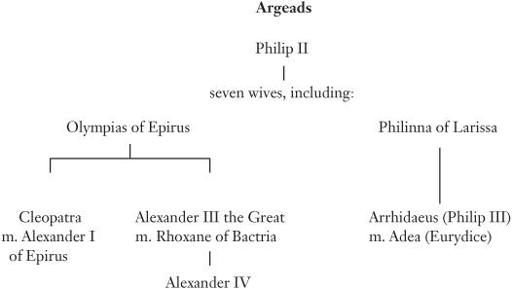

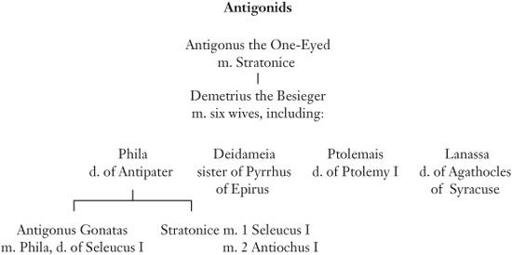

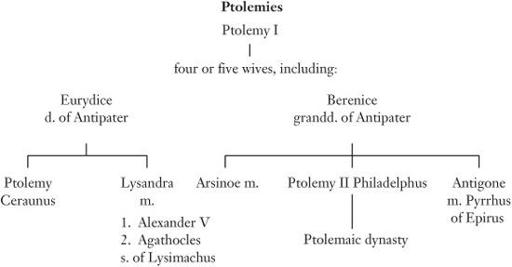

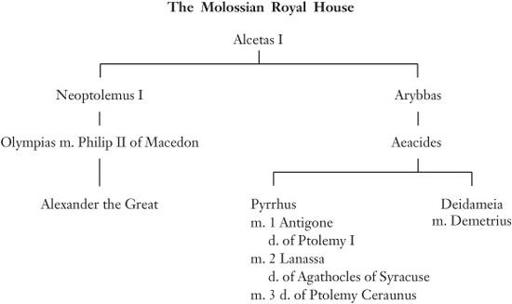

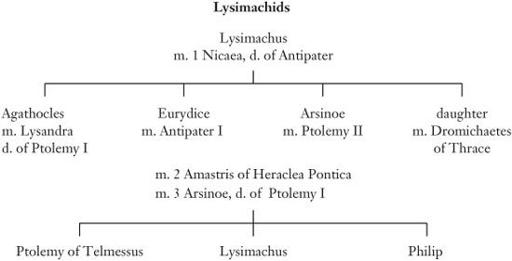

None of these genealogies is complete. For fuller versions, and more trees, see F. W. Walbank et al. (eds),

The Cambridge Ancient History

, vol. 7.1:

The Hellenistic World

(2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 484–91, or P. Green,

Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 732–9.

Note that Arsinoe, who married her brother Ptolemy II, had previously been married to Lysimachus and then to her half brother Ptolemy Ceraunus, while Ptolemy II had previously been married to another Arsinoe, the d. of Lysimachus.

Abbreviations

Ager = | Ager, S., 1996, |

Austin = | Austin, M., 2006, |

Bagnall/Derow = | Bagnall, R., and Derow, P., 2004, |

Burstein = | Burstein, S., 1985, |

Curtius = | Quintus Curtius Rufus, |

DS = | Diodorus of Sicily, |

FGrH | Jacoby, F., |

Grant = | Grant, F., 1953, |

Harding = | Harding, P., 1985, |

Heckel/Yardley = | Heckel, W., and Yardley, J. C., 2004, |

Justin = | Marcus Junianus Justinus, |

SSR | Giannantoni, G., 1990, |

Welles = | Welles, C. B., 1934/1974, |

Preface

1

. Plutarch,

Life of Alexander

8.2.

2

. See I. Morris, “The Greater Athenian State,” in Morris and Scheidel 2009, 99–177; and note that Polybius does not include the Athenian “empire” in his survey of empires prior to the Roman one (

Histories

1.2).

3

. Willa Cather,

O Pioneers!

, p. 44, Penguin ed.

Chapter 1

1

. Arrian,

Anabasis

24–6 relates this story, along with other glimpses of Alexander’s last days; see also the other texts translated in Heckel/Yardley, 272–80.

2

. The symptoms are described by Plutarch,

Life of Alexander

73–7, and Arrian,

Anabasis

24–6. The main innocent suggestions are malaria (Engels 1978a; Hammond 1989b, 304–5), peritonitis (Ashton/Parkinson 1990), acute surgical complications (Battersby2007), and encephalitis (Marr/Calisher 2003). Bosworth1971 cannot rule out poisoning on historical grounds, nor can Schep2009 on medical grounds. We owe accurate knowledge of the time of Alexander’s death to Depuydt1997.

3

. Curtius 10.10.14.

4

. Plutarch,

Life of Agesilaus

15.4.

5

. On Hyperides: Ps.-Plutarch,

Lives of the Ten Orators

849f. On Cassander: Plutarch,

Life of Alexander

74.2–3. The story sounds over-melodramatic, but it may contain an element of truth.

6

. On this document, the

Royal Ephemerides

or

Royal Journal

, see especially Bosworth1971 and Hammond 1988. Another version of its value as propaganda is given by Heckel 2007. The view that it was a much later forgery is argued by, e.g., L. Pearson, “The Diary and Letters of Alexander the Great,”

Historia

3 (1955), 429-55; repr. in Griffith 1966, 1–27. in Griffith 1966.

7

. DS 16.93.7; Justin 9.6.5–6.

8

. “Satrapy” is the term for a province of the Achaemenid empire; a “satrap” was the governor of a satrapy.

9

. For Alexander’s innovatory style of kingship, see Fredricksmeyer 2000 and Spawforth 2007; for Alexander’s attitude toward easterners, Bosworth 1980.

10

. Carney 2001. Guesses began in antiquity: see e.g. Plutarch,

Life of Alexander

77.5; DS 18.2.2.

11

. Bosworth 2000; Heckel 1988; text in Heckel/Yardley, 281–89. Heckel skillfully argued for a date early in 316 for the forgery, but Bosworth’s 308 seems more plausible.

12

. A talent was the largest unit of Greek currency. In this book I have assumed that one talent had a spending power equivalent to $600,000. Greek money was not on the whole fiduciary, but worth its weight; the primary meaning of “talent” is a weight—close to 26 kgs (somewhat over 57 lbs). The breakdown is as follows: 36,000 obols = 6,000 drachmas = 60 minas = 1 talent. A mercenary soldier in the period covered in this book might expect to receive at most 2 drachmas a day, to cover all his expenses; see Griffith 1935/1984, 294–307.

13

. DS 18.4.1–6. Some scholars doubt the authenticity of all or some of the “Last Plans”: see e.g. Hampl in Griffith 1966. But see e.g. Hammond 1989b, 281–85.

14

. See Fraser 1996.

15

. DS 18.8.2–7; Justin 13.5.2–7; Curtius 10.2.4.

16

. DS 18.8.4.

17

. Justin 13.1.12, clearly speaking with hindsight.

18

. Arrian,

Anabasis

7.26.3; Curtius 10.5.5; Justin 12.15.8; DS 17.117.4.

Chapter 2

1

. On this practice in Persia, see Briant 2002, 302–15; in Macedon, Hammond 1989a, 54–5.

2

. Slightly distorted in Curtius 10.5.16.

3

. This percolation is presented by Curtius (10.6–10) as the physical presence of ordinary troops in the meeting room. None of our other sources for these events (Justin 13.2–4; DS 18.2–3; Arrian,

After Alexander

fr.1.1–8) contains this feature, and I judge it to be a dramatic or distorted way of representing the percolation. Otherwise I have broadly followed Curtius’s account. There are, however, serious difficulties with Curtius and all the sources, not least that, implausibly, none of them has the meeting paying any attention to Arrhidaeus until forced to do so. The extant accounts read more like dramatizations of the main issues than reliable accounts of who proposed what. Other discussions of the Babylon meetings: Atkinson/Yardley 2009; Bosworth 2002, ch. 2; Errington 1970; Meeus 2008; Romm 2011, ch. 2.