Do Elephants Jump? (23 page)

Read Do Elephants Jump? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Sometimes life is not simple. Peanuts are not nuts (they are legumes). Peanut butter isn’t butter (there are no milk products in peanut butter). Peanuts aren’t sticky (but peanut butter is).

It’s not like we would use peanut butter in lieu of Krazy Glue, but along with reader Richard Rothstein, we wonder what happens to the 850 whole shelled peanuts that go into one eighteen-ounce jar of peanut butter to up their stickiness quotient. You’ve probably seen peanut butter ground from fresh salted peanuts in health food stores. No other ingredients are added, and yet the end result is as sticky as the best-selling commercial brands, such as Skippy, Jif, and Peter Pan, which may contain small quantities of sugar or stabilizers (usually vegetable oil-based, to prevent the natural oil in the peanuts from separating). Although we thought that perhaps added oils were responsible for the stickiness of peanut butter, all of our sources agreed that the answer lies elsewhere.

What exactly is stickiness? When we think of a sticky substance, we tend to think of glue or masking tape, something that adheres to other stuff. But in its simplest terms, when a substance’s molecules bond together in some way, we call it sticky. The stronger the bond, the stickier it is. Although peanut butter has some adhesive qualities (dip your finger into a jar of Skippy and see how well the peanut butter clings), its adhesive qualities are not strong enough to tempt us to try securing a box of books with it.

But there’s another form of stickiness — viscosity. A viscous fluid resists flowing, and resists changing form when subjected to an outside force. We usually equate fluids with liquids, but thick substances such as peanut butter can be considered a fluid and possess a viscosity. Water has low viscosity and flows quickly and smoothly and can be stirred with a spoon with virtually no resistance. High-viscosity fluids, such as tar and motor oil, do not move so efficiently, and peanut butter, as you might suspect, isn’t likely to flow down a drain easily. Try stirring peanut butter (as fans of “natural” peanut butter are likely to do to mix the oil that rises to the top with the rest of the “butter”) — it’ll strengthen your wrist.

On a plate or in our mouths, we tend to perceive high-viscosity foods as sticky, but not in the same way as the Jujubes that have clung to our teeth or the burned eggs that have stuck to an untreated frying pan. When we spread peanut butter with a knife, some of it sticks to the utensil, partly from adhesion, but mostly because adjacent molecules in the peanut butter stick together because of the food’s high viscosity — the peanut butter resists flowing — it wants to stay in the same shape it was in.

Of the two main reasons why peanut butter is stickier than peanuts, both have to do with the higher viscosity of peanut butter. The first culprit is the size of the nut particles used in peanut butter. We corresponded with Harmeet S. Guraya, a research food technologist at the Agricultural Research Service, a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Guraya, whose specialty is analyzing the textures and flavors of food, wrote:

When you eat peanuts, when the particles are bigger during initial rupture or breakup of peanut, it is easy to chew. When you masticate the peanut and make it into a fine paste, then it gets sticky in your mouth. Commercial machines that make peanut butter grind the peanuts to different particle sizes, which is why you have different [levels of] stickiness [and thus spreadability] in different brands.”

Although it may seem counterintuitive, the

smaller

the particle size, the more viscous the final product will be. This explains why if you keep chewing peanuts, it gets harder and harder to chew as you progress — you are making peanut butter in your mouth!

The second reason why peanut butter is stickier than peanuts is that the grinding of the peanuts changes the molecular structure of the legume, releasing more viscous components. Sara J. Risch, Ph.D., a food scientist and consultant to the Institute of Food Technologists, told

Imponderables

:

In whole peanuts, the components such as the proteins and carbohydrates are enclosed in cells and held together. When the peanuts are ground, all of the cells are broken down and these materials released. This yields a material that is very viscous and thus sticky to the touch. Some of the stickiness [of the final product] could also be due to the proteins and carbohydrates. It is not from the oil.

Guraya emphasizes that viscosity is not the same thing as stickiness, and that

the sensory perception of stickiness could be due to a variety of reasons for different foods. When I gave you the reasons for stickiness of peanut butter, it pertains only to peanut butter, although the definition of stickiness stays the same.

Although a few other factors, such as the type of stabilizers and the inclusion of high-moisture peanuts, can up the viscosity quotient of peanut butter, the grinding process itself explains the perception of stickiness. Americans must not mind coating the roofs of their mouths with the stuff — just short of one-half of the entire U.S. peanut crop is used to make peanut butter.

| Submitted by Richard Rothstein of Haddonfield, New Jersey. |

Japanese society is sometimes accused of insularity, yet the country has not only adopted American baseball as its favorite team sport, but displays the names of its heroes in English. How did this happen?

Most historians date the birth of baseball in Japan to the early 1870s, at what is now Tokyo University. Horace Wilson, an American professor, taught students how to play. According to Ritomo Tsunashima, an editor and writer who writes a column about uniforms for

Shukan Baseball

magazine in Japan, these students were probably then wearing kimonos and hakama (trousers designed to be worn with kimonos).

In 1878, the Shinbashi Athletic Club established the first baseball team in Japan, and they were the first team to wear a uniform. The team’s founder, Hiroshi Hiraoka, was raised in Boston, Massachusetts, and bought the equipment and uniforms to conform to what he saw in the United States at that time. Tsunashima observes that in the early days of the game in Japan,

The players of baseball were fans of the Western style of life, and they were fond of Western culture. When exactly alphabet letters appeared on uniforms is unknown, but likely it was shortly after letters appeared on uniforms in the United States.

The first professional team in Japan that had uniforms with printed English words and names was founded in 1921, but disbanded in 1929. But in 1934, a U.S. all-star team containing such legendary figures as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig visited Japan. To challenge the visitors, Japan assembled a team that eventually became the Yomiuri Giants. When the Giants returned the favor the following year and visited the United States, their uniforms contained the kanji (i.e., Japanese) alphabet and numbers, but this was an anomaly.

When the first professional baseball league formed in Japan in 1936, the players appeared with an English alphabet and Arabic numbers on their front — the Tokyo Giants appeared with “Giants” emblazoned on their chests. During World War II, kanji characters reappeared, as Western symbols were obviously frowned upon. Tsunashima writes:

Professional baseball continued during the bombing raids by the United States in 1943, but playing baseball was finally forbidden in 1944. After World War II, professional baseball started again with the English language [on the uniforms], and kanji letters were never used again.

Why has English superseded kanji, especially when amateur and school baseball teams usually use Japanese characters? We haven’t been able to find any answer more fitting than Robert Fitts’s, owner of RobsJapaneseCards.com:

Because it’s cool. Just the same as when people call me and say, “I want Japanese baseball cards written in Japanese,” and I have to tell them, “They don’t make them.”

| Submitted by Marshall Berke and Chris Tancredi of Brooklyn, New York. |

Our hair color is determined by genetics, but in some cases Mother Nature chooses to not reveal our ultimate hair color until well into adolescence. During infancy, the melanocytes, skin cells that mark and deposit pigment, are not fully active, and don’t function in many children until sometime during adolescence.

Scientists still don’t understand exactly why hair darkening occurs in fits and starts throughout childhood and adolescence, and differs so radically from person to person. Dermatologist Joseph Bark, author of

Skin Secrets: A Complete Guide to Skin Care for the Entire Family,

wrote

Imponderables

that the eventual darkening of hair color seems to be a

slow maturation process rather than a hormonally controlled process associated with the “juices of puberty,” which causes so much else to happen to the skin of kids.

As is often the case with medical questions that are curious but have no practical application (or grant money attached), the definitive solution to this Imponderable is likely to remain elusive. As Chesapeake, Virginia, dermatologist Samuel Selden celebrates:

I don’t believe that much study has been made of this, and until that is done, it means that armchair speculators like myself can have a field day with answering questions like this.

| Submitted by Debra Allen of Wichita Falls, Texas. Thanks also to Chester A. Tumidajewicz of Amsterdam, New York; Tina Litsey of Raceland, Louisiana; and Edward Litherland of Rock Island, Illinois. |

We hope that trained musicians will bear with us while we cover (and simplify) a few basics so that even we music illiterati can understand the answer to this Imponderable. Even those of us who don’t play music are familiar with the musical staff, which looks something like this:

By the arrangement of notes on this staff, a musician can tell how high or low the notes should be (the pitch), when each note should start (temporal position), and how long each note should last (duration). The notes are named after the first seven letters of the Roman alphabet, starting with A on the bottom until G is reached. Notes may be placed on a line, in the space between lines, or above the top line or below the bottom line of the staff.

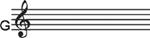

If instruments had a range of notes that could be encompassed by the five-line staff, life would be much easier for composers and musicians. But there are many more notes on a piano, for example, than can be annotated within a five-line staff. One way of simplifying this problem is by inserting a clef at the far left side of the staff (all sheet music is read from left to right, even in Israel). The clef’s job is to inform musicians what pitch the first note of the piece will be played in, and therefore determining the pitch of all the other notes on that staff in relationship to the clef. To answer the second part of this Imponderable first, the fancy curlicues on the clefs are not just for effect — they point out the pitch of the first note on the staff.

Probably the most familiar clef is the treble clef, also known as the G clef. The end of the inside curlicue (the fine tip that looks like a tail) marks the line, usually the second from bottom line, where the G note is designated:

Look at the G clef again and you’ll see that the entire clef is a stylized, cursive rendering of the letter

G.

Lesser known is the alto clef, where the middle C note is marked by the center of two stylized backward

C

s:

The middle C would lie on the middle line; D would be in the space between the C line and the line above it (the E line).

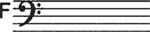

And now we get to the star of our Imponderable, the bass clef. As you’ve probably guessed, the bass clef also marks a line, in this case the F below middle C. On a piano, the left hand is usually following the instructions on a staff headed by a bass clef, while the right hand is written in treble clef. The bass clef looks like this:

Those two dots aren’t to the right of the clef — they are actually part of the clef and essential for two reasons. Just as the treble clef is the rendering of a cursive letter

G,

the bass clef is a rendering of the letter

F.

Those two dots are a stylized expression of the two limbs coming off the base of the

F.

And just like the G and C clefs, the stylization has a purpose, as Michael Blakeslee, of the Music Educators National Conference puts it: “To help the reader zero in on the note defined by the clef, the dots appear above and below the line for the F note.”

Our musical staves are the descendants of a Benedictine monk, Guido d’Arezzo, who lived in the early eleventh century and composed chants. He faced the problem of how to teach his monks new chants before the advent of standardized musical notation, and an even more daunting task of imparting his new music to priests in far-flung monasteries. D’Arezzo developed the notion of using his hand as a way of dictating the pitch of his chants. He held his left hand with his palm facing away from him, fingers in horizontal position, and pointed to the four fingers (the thumb wasn’t long enough to provide enough information). The knuckles and joints would indicate timing (horizontally), the choice of finger (vertically) would indicate pitch. Our musical staff was adapted from the “Guidonian hand” (the first musical staves contained only four lines, the equivalent of d’Arezzo’s left forefinger, middle finger, ring finger, and pinkie), which used a six-note scale.

D’Arezzo continued to think of ways to standardize musical notation. One of his great contributions was the solfeggio, a group of six syllables designed to serve as a mnemonic to correspond to the notes in his system. Five of them will sound familiar: “ut re mi fa sol la.” Why wasn’t it “

do

re mi”? These syllables were not nonsense sounds, but rather from the first syllables of Latin phrases in a well-known chant in honor of St. John, “Ut Queant Laxis.” (“

Ut

queant laxis,” “

Re

sonare fibris,” “

Mi

ra gestorum,”

Fa

muli tuorum,” “

So

lve polluti,” and “

La

bii reatum.”). Because everyone knew this chant, the solfeggio became the answer to two choruses singing the same note at the same pitch without the benefit of musical notation.

Why was ut replaced by do? We’d like to think it was to make Rodgers and Hammerstein’s life a little easier (it’s easier for Julie Andrews to sing a song that starts with a reference to a female deer than to an ut!), but history records a more prosaic answer. Another Italian, Giovanni Maria Bonocini, suggested the retirement of ut in 1673, because of the more open, mellifluous sound of do compared to the closed, harsh ut. And probably at least as important, do represents

Dominus,

the Latin word for “Lord.”

The difficulties in developing a universal system of musical notation were exacerbated by the difficulties of disseminating scores. Even after the invention of the press, printing sheet music was a technical nightmare. Today, with computer programs and photocopying, the costs are relatively trivial, even if the music isn’t necessarily any better than it was centuries ago.

| Submitted by David Ward of Oakville, Ontario. Thanks also to James King of Honolulu, Hawaii; and Donald Ullrich of Burlington, Iowa. |