Do Elephants Jump? (4 page)

Read Do Elephants Jump? Online

Authors: David Feldman

The tradition of name changes for Church officials dates back to the beginnings of the Christian movement. In the Book of Matthew, Jesus appoints his disciple Peter to be the first head of the Church. Yet Peter’s birth name was Simon.

According to Lorraine D’Antonio, the retired business manager of the Religious Research Association,

Their names were changed to signify the change in roles, attitudes, and way of life. When the Pope assumes his role as head of the Church, it is assumed that he will change his life as his name is changed when he dedicates his total being to the service of the Church. Quite often, when a person dedicates his or her life to the service of God (during ordination, confirmation, etc.), the person assumes a new name, as he or she assumes a new role and commitment.

The first pope who we know changed his name was John II, in

A.D.

533. Presumably, his given name, Mercurio, a variation of the pagan god Mercury, was deemed unsuitable for the head of the Church. So Mercurio paid tribute to John I by adopting his name.

No other Pope changed his name until Octavian chose John XII for his papal name in 955. A few decades later, Peter Canepanova adopted John XIV. Brian Butler, president of the U.S. Catholic Historical Society, told

Imponderables

that John XIV was the first of several popes with the given name of Peter to start a tradition — no pontiff has ever taken the name of the Church’s first pope.

Butler notes that the last pope to keep his baptismal name was Marcellus II, born Marcello Cervini, who served in the year 1555.

| Submitted by David Schachow of Scarborough, Ontario. |

Let’s put it this way: If identical twins had identical fingerprints, do you really think David Kelley wouldn’t have fashioned a murder plot about it on

The Practice

? Or Dick Wolf on one of the seventy-four

Law and Order

spinoffs?

Scientists corroborate our TV-based evidence. Identical twins result when a fertilized egg splits and the mother carries two separate embryos to term. The key to the creation of identical twins is that the split occurs

after

fertilization. The twins come from the same sperm and egg — and thus have the same DNA, the identical genetic makeup.

Because their DNA is an exact match, identical twins will always be the same sex, have the same eye color, and share the same blood type. “Fraternal twins,” on the other hand, are born when two separate eggs are fertilized by

two different

sperms. Their DNA will be similar, but no more of a match than any other pair of siblings from the same parents. Not only do fraternal twins not necessarily look that much alike (think, for example, of the Bee Gees brothers, Maurice and Robin Gibb), but can be of the opposite sex and may possess different blood types.

Even though identical twins share the same DNA, however, they aren’t carbon copies. Parents and close friends can usually tell one identical twin from the other without much difficulty. Their personalities may differ radically. And their fingerprints differ. If genetics doesn’t account for these differences, what does? Why aren’t the fingerprints of identical twins, er, identical?

The environment of the developing embryo in the womb has a hand in determining a fingerprint. That’s why geneticists make the distinction between “genotypes” (the set of genes that a person inherits, the DNA) and “phenotypes” (the characteristics that make up a person after the DNA is exposed to the environment). Identical twins will always have the same genotype, but their phenotypes will differ because their experience in the womb will diverge.

Edward Richards, the director of the program in law, science, and public health at Louisiana State University, writes:

In the case of fingerprints, the genes determine the general characteristics of the patterns that are used for fingerprint classification. As the skin on the fingertip differentiates, it expresses these general characteristics. However, as a surface tissue, it is also in contact with other parts of the fetus and the uterus, and their position in relation to uterus and the fetal body changes as the fetus moves on its own and in response to positional changes of the mother. Thus the microenvironment of the growing cells on the fingertip is in flux, and is always slightly different from hand to hand and finger to finger. It is this microenvironment that determines the fine detail of the fingerprint structure. While the differences in the microenvironment between fingers are small and subtle, their effect is amplified by the differentiating cells and produces the macroscopic differences that enable the fingerprints of twins to be differentiated.

Influences as disparate as the nutrition of the mother, position in the womb, and individual blood pressure can all contribute to different fingerprints of identical twins.

Richards notes that the physical differences between twins widen as they age: “In middle and old age [identical twins] will look more like non-identical twins.”

About 2 percent of all births are twins, and only one third of those are identical twins. But twins’ fingerprints are like snowflakes — they may look alike at first blush, but get them under a microscope, and the differences emerge.

| Submitted by Mary Quint, via the Internet. Thanks also to Rachel P. Wincel, via the Internet; and Stephanie Pencek, of Reston, Virginia. |

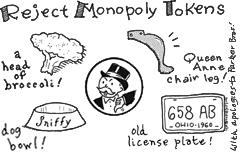

What do a thimble, a sack of money, a dog, a battleship, and a top hat have in common? Not much, other than that they are among the eleven playing tokens you receive in a standard Monopoly set. And don’t forget the wheelbarrow, which you’ll need to carry all that cash you are going to appropriate from your hapless opponents.

The history of Monopoly is fraught with contention and controversy, for it seems that its “inventor,” Charles Darrow, at the very least borrowed liberally from two existing games when he first marketed Monopoly in the early 1930s. After Darrow self-published the game to great success, Parker Brothers bought the rights to Monopoly in 1934.

On one thing all Monopoly historians can agree. When Parker Brothers introduced the game in 1935, Monopoly included no tokens, and the rules instructed players to use such items as buttons or pennies as markers. Soon thereafter, in the 1935–1936 sets, Parker Brothers included wooden tokens shaped like chess pawns: boring.

The first significant development in customizing the playing pieces came in 1937, when Parker Brothers introduced these die-cast metal tokens: a car, purse, flatiron, lantern, thimble, shoe, top hat, and rocking horse. Later in the same year, a battleship and cannon were added, to raise the number of tokens to ten.

All was quiet on the token front until 1942, when metal shortages during World War II resulted in a comeback of wooden tokens. But the same mix of tokens remained until the early 1950s, when the lantern, purse, and rocking horse were kicked out in favor of the dog, the horse and rider, and the wheelbarrow. Parker Brothers conducted a poll to determine what Monopoly aficionados would prefer for the eleventh token, and true to the spirit of the game, the winner was a sack of money.

Parker Brothers wasn’t able to tell us why, within a couple of years, Monopoly went from having no tokens, to boring wooden ones to idiosyncratic metal figures. Ken Koury, a lawyer in Los Angeles who has been a Monopoly champion and coach of the official United States team in worldwide competition, replied to our query:

Monopoly’s game pieces are certainly unique and a charming part of the play. I have heard a story that the original pieces were actually struck from the models used for Cracker Jack prizes. Any chance this is correct?

We wouldn’t stake a wheelbarrow of cash on it, but we think the theory is a good one. We contacted author and game expert John Chaneski, who used to work at Game Show, a terrific game and toy emporium in Greenwich Village, who heard a similar story from the owner of the shop:

When Monopoly was first created in the early 1930s, there were no pieces like we know them, so they went to Cracker Jack, which at that time was offering tiny metal tchotchkes, like cars. They used the same molds to make the Monopoly pieces. Game Show sells some antique Cracker Jack prizes and, sure enough, the toy car is exactly the same as the Monopoly car. In fact, there’s also a candlestick, which seems to be the model for the one in Clue.

John even has a theory for why the particular tokens were chosen:

I think they chose Cracker Jack prizes that symbolize wealth and poverty. The car, top hat, and dog [especially a little terrier like Asta, then famous from the “Thin Man” series] were possessions of the wealthy. The thimble, wheelbarrow, old shoe, and iron were possessions or tools of the poor.

| Submitted by Kate McNieve of Phoenix, Arizona. Thanks also to Mindy Sue Berks of Huntington Valley, Pennsylvania; Flynn Rowan of Eugene, Oregon; and Sue Rosner of Bronx, New York. |

When you buy fresh sweet corn, throw away the husk and silk, and gaze upon the kernels of yellow or white corn, not a black speck is in sight. Boil the corn in a pot or grill them on the barbecue, and no specks appear. So why, when we gaze upon a Frito or grab a mound of Doritos, can we see “freckles” on every single chip? We’ve noticed that the specks seem dark on most corn chips and yellow corn tortilla chips, and lighter but still easily visible on cheese-flavored chips and plain white corn tortilla chips (the difference between yellow and white corn is due to a few pigments in the outer layers of the corn kernel).

We called the folks at Frito-Lay, which makes both of these brands, and they swore up and down that they did nothing to add specks to the chips. Frito-Lay uses whole corn kernels and grinds and cooks them in-house to make Fritos and Doritos. The customer service representative, who preferred to remain anonymous, assured us that the specks are not pepper. They are not burn marks or signs of an overcooked chip (if so, then every chip they sold would be burnt). “So what are they, then?” we demanded. “Errrr…” she responded.

Actually, this Imponderable stumped a bunch of experts, including professors and researchers who specialize in corn. We called Irwin Steinberg, our old pal and executive director of the Tortilla Industry Association, who despite his many years in the business, professed that he has never been asked about the black specks that are also evident in corn (but not flour!) tortillas or tortilla chips. But he knew where to send us: to two professors “who’ll know the answer to your questions.”

Our heroes are Lloyd Rooney, chairman of the Food Science faculty and Ralph Waniska, professor of soil and crop sciences at Texas A&M. We grilled them separately and both told us the same story, so either they are foisting an elaborate hoax on us, or this Imponderable has been solved!

On the tip of each corn kernel is a hilum, collectively known as the “black layer,” where it is attached to the cob. While corn is growing, nutrients are being transferred from the rest of the cob to the kernels through the hilum. The hilum serves a function for the corn not unlike a belly button attached to a human umbilical cord serves for a human fetus — it’s a nutritional supply line to the rest of the kernel.

But the hilum is not always black. As the corn matures, the hilum turns from unpigmented to light green to light brown to brown and eventually to black. When the corn is fully mature, the hilum is black and nutrients are no longer being sent to the kernel.

If mature corn forms a black layer, and every kernel has a black tip, then why don’t we see it in sweet corn? The answer is that sweet corn for the home table is picked more than a month before the corn used by the chip companies, before the hilum discolors.

When corn is starting to grow, most of the kernel is composed of moisture. As they mature, the kernels gain starch and lose some of their “milk.” Sweet corn is picked when the corn is at maximum sweetness, and there is still plenty of moisture within the kernel. Fresh sweet corn commands a premium price. But industrial food processors would rather wait longer to pick corn for tortilla chips or feed grain for cattle, because as corn continues to lose moisture and gain more starch, it provides more usable product.

Some chip companies, rather than using the whole corn and creating the masa themselves (which involves boiling corn in a lime solution, rinsing, draining, grinding, and then drying the corn and forming it into a doughlike consistency), buy prepared dry masa flour and the black specks aren’t as prevalent. If the flour was made with the outer layer of the kernel removed, there may be no specks at all. Too bad, because as Rooney says, “the hilum is probably a good source of fiber and perhaps antioxidants and is not detrimental in any manner.”

Indeed, some consumers, hip to the hilum, equate a lack of specks with inauthentic chips. So some crafty snack food companies actually buy the hila (the plural of hilum) separately and add them to the dough to pass off their chips as though they were “made from scratch.” We cry foul!

Why do white tortilla chips have fainter specks than yellow ones? Because white corns have lighter hila.

And why do cheese-flavored yellow tortilla chips, such as Nacho Cheese Doritos, sport lighter specks? Because the flavorings are partially obscuring the specks. The cheese is like a cosmetic palliative — a speck concealer.

| Submitted by Melissa Taylor of Holland, Michigan. Thanks also to Dot Finch of Soddy-Daisy, Indiana. |