Don't Breathe a Word (7 page)

“She knew your name,” said Phoebe. “Just before you chased her into the woods, she said your name. Maybe she saw it when she was going through our things.”

“No,” said Sam. “There’s more to it than that. That weak little lamb-y thing she said—it was a rhyme Lisa used to tease with me with. No one else knows about it.” There went Sam’s shoulders, back into the slouched, little boy position.

“So, what? Are you saying you think this girl is Lisa?”

“No! Definitely not.” The state trooper ahead of them turned to look back. Sam continued, lowering his voice. “But it’s like she knows her. Or knows things about her.”

“Maybe she’s from the land of the fairies,” Phoebe ventured, knowing how ludicrous it sounded.

Sam shook his head. “Jesus! There is no land of the fairies, Bee. Lisa was taken by a real person to a real place. Shit, she probably never even made it out of those woods alive.”

Phoebe felt a rush of guilt. She’d been so compelled by the idea of the fairies and the book that she’d forgotten the facts: Sam had lost his sister to what was most likely a brutal, and terribly human, crime. She needed to be more gentle and supportive, beginning with backing off from the crazy fairy talk.

She took Sam’s hand, broadening her own shoulders. She would be the strong one here. She’d get them out of this. She had the stone in her pocket as proof, damn it, and that counted for something.

Eventually they came to a small clearing, and there, at the base of a tree, was a length of rope. And a pile of clothing along with a small knapsack. It was all just as the redhead described.

The girl reached into the bag and came out with a wallet. She showed the police a state college ID that said her name was just what she’d told them it was: Amy Pelletier.

“No driver’s license?” one of the cops asked.

“I don’t drive,” Amy said.

“Maybe you should learn,” suggested the constable. “I’d say it’s high time you gave up hitchhiking.”

“No shit,” said Amy as she gathered up her belongings. “Look, I was scared out of my mind, but no harm was done, right? I’d just as soon drop the whole thing.”

“But these people committed a crime. They held you against your will.”

“Maybe it was just a game. Maybe at first I played along, okay? They’re kind of cute, I was into it. A little bondage isn’t such a bad thing. Maybe I just kind of freaked. Let’s just forget it, okay? I got my stuff back. I just want to walk away and pretend it never happened.”

“You don’t want to press charges?” one of the cops asked, dumbfounded.

“No. I just want to go home.”

Alfred the constable took the girl aside and spoke quietly to her for a minute. She shook her head, said something that made him laugh.

“If you’re sure . . .” said the constable. Then he turned back to the others. His ears were bright red, like strange glowing handles on the side of his juglike head. “I’m going to give Amy a ride into town. Take her to the diner for some breakfast and a chance to get cleaned up, use the phone . . .”

The constable put his arm around the girl and nodded at the cops, then led her away, his ears and neck redder than ever.

“I think you should consider yourselves very lucky,” said one of the cops. “But she could still change her mind. If she decides to press charges after all, we know where to find you.” Then they turned to go.

“Wait! How do we find our car?” asked Sam.

“That way,” pointed one of the cops. “Route 12 is about half a mile.”

T

hey walked in dazed silence.

“Shit!” Sam mumbled. “My keys. I don’t have any keys. They were on the dresser at the cabin.”

“There’s one under the car.”

“There is?”

“I put it there last winter after I locked myself out and had to call AAA. Remember?”

“I told you not to,” Sam said.

“But I did it anyway, and now aren’t you glad?”

He didn’t say anything.

“Do you have your wallet?” she asked him.

“That’s about all I do have.”

“What are we going to do?”

“Go home. We’re going to go home.”

They walked on in silence, and by the time they reached the Mercury, they were exhausted and hungry. Phoebe looked beneath the car and found the little magnetic box under the rear bumper, right where she’d left it back in January. It had rusted closed and she pounded it open with a rock. She was bringing the key to Sam, closed in her palm like a secret, when she saw him remove a small piece of paper that had been tucked under the windshield wiper.

“A ticket? You’ve gotta be kidding.”

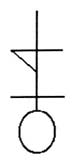

“It’s not a ticket,” Sam said. What little color left in his face drained away as he studied the paper. Phoebe noticed the faintest tremor in his hand. She came up beside him and looked down at the paper. There were no words, only a simple picture. Lines and a circle, like something a child would do.

It was the same mark she’d seen on Elliot’s calf.

“Teilo,” he mumbled.

“What?”

“Not what, who. Teilo. The King of the Fairies.”

Lisa

June 7, Fifteen Years Ago

L

isa got an old, chipped china saucer and laid out three sugar cubes, a flat piece of mica she’d found in the stream, a Lorna Doone cookie, and a juice glass full of Orange Crush.

“The only thing you’re going to attract with all this is yellow jackets,” Sammy complained as they made their way across their backyard and into the woods. Sammy had on a black T-shirt with a map of glow-in-the-dark star constellations. His hair was too long and was sticking out all over the place. Da always cut Sammy’s hair. He’d set up a chair in the kitchen, lay out the scissors and comb, and announce, “The barbershop is open!” He’d wet Sam’s hair in the kitchen sink, then drape a towel around his neck and sing out, “Shave and a haircut, two bits!” Sam would laugh and Da would talk like a barber. “What’ll it be today, son? Flattop? A little off the sides? Finish it off with a dab of Brylcreem?” Sam would giggle more. “A Mohawk, perhaps?” Da would tease, combing up the sides of Sam’s damp hair so that it was all in the middle, then showing him the mirror. “The stegosaurus look,” Da said. “It’s very in these days. You’ll be a hit with the girls. A real lady killer.”

Lisa was thinking that maybe she should offer to give Sam a trim but figured he’d probably refuse. He’d just let his hair keep growing until Da got better, looking more and more like a boy of the wild every day. Sammy didn’t give much thought to things like being presentable.

“You don’t know that,” Evie said. “Aunt Phyllis said fairies like sweets.”

“She’s just yanking your chain,” Sam said.

“So if you don’t believe me, why’d you come?” Lisa asked, squinting back over her shoulder at her brother.

“ ’Cause I want to see your face when nothing happens,” he said.

Lisa was walking extra carefully, her high-wire balance walk, so that she wouldn’t spill anything on the plate. The hill that led down toward Reliance was uneven and steep in places. The ground was spongy with fallen leaves rotted to mulch. There were rocks and downed branches to trip on, but if you knew where to look, there was a path the kids kept clear that led all the way down to Reliance. All around them, young poplar and birch fought for scraps of light under the canopy of full-grown maple and beech trees. The woods had a rich, loamy scent that always made Lisa take deep, hungry breaths. Even though it was only ten, it was hot already and it felt good to enter the woods and get out of the sun. The drying sweat on her arms and legs felt prickly and cool.

“What, are you guys having a picnic or something?” called a voice from up ahead of them. Great. This was not what they needed at all. Gerald and Becca were coming up from Reliance. Gerald was wearing camouflage pants and a

Star Trek

T-shirt. He had big square wire-framed glasses that were the kind that got darker when you were out in the sun. The problem was that they seemed really slow to get back to normal, and now that he was in the dark forest, he was squinting, struggling to see through them. Becca was always in pink and today was no different—matching shorts and shirt the color of cotton candy. Pink flip-flops. Her hair was even tied back with a pink ribbon. What a kook. She was in Sammy’s grade and he said that she thought she was popular, but secretly everyone kind of hated her. “She tries too hard,” Sammy explained. “Like WAY too hard. It’s kind of painful to watch.” Her schoolmates called her Pinkie, which she liked. Lisa had thought it wasn’t so bad until the day she went to the pet shop and saw that the little newborn mice they sold to people who owned snakes were called pinkies. Now, whenever she saw Becca, she thought of those tiny, blind embryo-like creatures that didn’t stand a chance.

“Yup,” Lisa said, wanting to get rid of them quickly, whatever it took. There was no way she was going to tell them the truth about the plate of gifts or mention anything about what they’d seen the night before. And she didn’t want to give Gerald a chance to start giving Evie any crap or calling her Stevie.

“Kind of a strange-looking picnic,” Gerald said, peering down at the plate now that he was up close. He’d pushed his still-too-dark glasses down and was looking over the top of them. His light brown hair was a little greasy, and his forehead was dotted with pimples.

Gerald, at least, didn’t have any illusions about being popular. He had his small circle of friends—boys who liked computer games, model building, and graphic novels—and that was enough. He was content hanging out in the computer lab after school, where he and his buddies were working on designing their own game, which took place in an alternate, microscopic universe and required them to invent a whole new language they called Minarian. Lisa kind of admired Gerald for knowing just who he was and not pretending to be anything more. But still, he got teased by some of the other boys—the popular, athletic boys who already had girlfriends they went to the movies with on Friday nights.

“Ant food,” Sammy said. “We’re giving a picnic to the ants.”

Gerald laughed. “You guys are so weird.” It was a favorite line of his. Something he said to Lisa all the time:

You’re so weird.

But he said it with a goofy smile on his face, like it somehow pleased him. Like he knew he was weird too, and he was acknowledging Lisa as part of his tribe.

This time, though, the smile faded quickly and his eyes went right to Evie. “Like freak show weird,” he said, snorting a little. Evie clenched her jaw and her breath got whistley-sounding. Her fingers rested on the knife in its sheath.

“I like ants,” Pinkie said, looking at Sam, smiling.

“You do not,” Gerald said, shaking his head, pushing his glasses back up. “You hate bugs!”

“An ant can lift twenty times its own body weight,” Sam told Pinkie. “That’s like you lifting a car.”

Pinkie giggled at this, scratched a bug bite on her arm.

“Now

that

I’d like to see,” Gerald said, making a silly, forced guffawing sound. Then he grabbed the shoulder of her pink T-shirt with ruffled sleeves and gave it a tug. “Come on, Hercules,” he said. Pinkie followed, still picking at the bug bite on her arm, which was now bleeding. “Au revoir!” she called back, giving a queen’s wave, hand cupped and wrist twisting in an unsettling Barbie-dollish way.

Evie took her hand off the knife.

“Thank God,” Lisa whispered. “I thought we were gonna be stuck with Gerald and Freaky Pinkie all day.”

Sam shook his head. “You’re the one bringing sweets to the fairies and you’re calling Pinkie the freak? I hate to say it, Sis, but you’re making her look downright normal.”

After another few minutes, they were crossing the brook, which mostly just ran in the early spring and was reduced to a sad little trickle the rest of the year. It was easy to clear in a single step, and even when you missed, you only got wet up to your ankle. Sometimes the brook dried up entirely, but it was always a good place to find red-backed salamanders staying cool under rocks.

Across the brook, the woods opened up, and they could see what was left of Reliance: half a dozen cellar holes lined with stones and crumbling mortar—some stunted lilacs and apple trees, the cemetery and old well. Encircling all this was a low, crooked, broken-down stone wall. The cellar hole closest to the brook was the one they’d seen the lights in the night before, and Lisa headed straight for it, Sammy and Evie in tow.

“Maybe it was swamp gas,” Sam said, pacing around, looking at the ground, then up at the trees.

“What?” Lisa asked, peering down into the cellar hole, which looked the same as ever. It was roughly a fifteen-foot square—the footprint of a house that hadn’t been very large at all, more like the size of a living room. She remembered the strong feeling she’d had last night as they stood in this same spot—that they were being watched.

“They say that it can glow,” Sammy explained. “Make strange lights.”

Evie shook her head. Laughed a little.

“Um, hello! Earth to Mr. Science—there’s no swamp here!” Lisa said. She loved Sammy. Deep down she did. But sometimes he was so dense it made her head hurt.

“Maybe the gas is escaping from a vent in the ground,” he said.

“Maybe,” Lisa told him at last. “Why don’t you take a long walk and see if you can find it.”

Evie chuckled.

Sammy looked totally unfazed. He walked in a circle around the cellar hole but showed no sign of going any farther. His forehead was all crinkled, like that of a fretful old man.

“Hold this, okay?” Lisa said, handing the plate over to Evie while she climbed down into the hole.

“Careful,” Evie said, eyes worried, lips trembling a little, as if Lisa was lowering herself into a nest of snakes.

They’d been in and out of this and every other cellar hole hundreds, maybe even thousands of times. Played countless games of hide-and-seek. They’d slain invisible dragons with stick swords and won wars with Vikings. They’d sung that silly “Say, Say My Playmate” song while they chased each other through the village, pretending they each had a house of their own with cellar doors and rain barrels. Reliance was like a second home to them. But today something was different. The woods didn’t feel like theirs alone anymore.

The cellar hole wasn’t deep—maybe four feet with crumbling stone walls and a dirt floor layered with years of rotting leaves. If Lisa squinted her eyes, she could just imagine the stone walls topped with a wood frame, clapboard siding. A little door and windows. There were old moss-covered bricks on the north side that must once have been a chimney and hearth.

“Do you think this could have been it?” she asked.

“What?” Evie asked.

“Eugene’s house,” she said. “Our great-grandfather.”

She remembered her mother this morning:

Sometimes I see him in each of you.

Evie nodded. “I wouldn’t be at all surprised. Your mom would know, probably. We should ask her.”

Lisa looked around the bottom of the cellar hole. Baby trees grew there—poplar, white pine, and clumps of ferns.

“Maybe the lights we saw were like . . . his ghost or something,” Evie said.

“Could be,” Lisa said, but she didn’t think so. It was fairies. Definitely. She was surer than she’d ever been of anything.

“Hey, guys, this is weird,” Sammy called, appearing at the edge of the foundation. “I found this just over in those trees.” He pointed to the left, near the old well. Lisa folded her arms over the edge of the cellar hole, pushing her belly against the wall, and looked up. Sammy held a half-eaten sandwich.

“Probably from Gerald and Pinkie,” Evie said. “Damn litterbugs!”

Sam studied the sandwich, gave it a sniff. “I think it’s liverwurst,” he said, wrinkling his nose.

The only person Lisa knew who ate liverwurst was Da, and he certainly wasn’t in any shape to be picnicking in the woods.

“Weird,” Lisa said.

“Gross,” said Evie. “I say you chuck it. Some animal will come along and eat it. Maybe. If it’s hungry enough.”

Lisa let go of the wall and turned from Sam and Evie and the offensive sandwich to study the inside of the cellar hole.

There, in the southernmost corner of the old foundation, right where they might have found little Eugene all alone, squalling in his cradle, Lisa saw a plant growing. It was hung with flowers like a string of bells. The flowers were pale purple with white spots going down their throats. Magic flowers. “I knew it,” Lisa exclaimed, clapping her hands together. She leaned down and listened, sure she would hear the sound of tinkling bells.

“Foxglove,” Sammy said from up above. “Be careful, they’re poison.”

Lisa had never seen such a spectacular flower, poisonous or not. And she couldn’t believe that anything in those woods would hurt her.

She set the plate of gifts carefully at the base of the plant and then, heart pounding, Sammy hissing warnings, she reached out and touched one of the flowers. It was soft and smooth, like the cheek of a baby.

She could almost hear Eugene’s long-ago cry: an infant alone in the woods, left behind.