Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (22 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

I look around, my face burning. But everyone else is having their possessions fingered in just the same way. I can tell the Old Hands from the New Hands. While the New Hands blush, sweat, and occasionally protest their treatment, the Old Hands have relaxed. They are chatting to each other, smoking cigarettes, ignoring the officials, waving to each other: “Where did you go?” “How was your trip?” “Join us for a beer later?”

“Do you have foreign currency?” My brookies and training bras, awkwardly neither childish nor yet grown-up, are brought out and shaken, as if money might fall from their folds.

“No.”

The officials frown, suspicious. “Then how will you pay your way while you stay in our country?”

“My mum and dad,” I say, my voice growing hoarse with near tears.

I burst breathlessly out into the steaming, humid air of the main airport where Mum, Dad, and Vanessa have grown bored, waiting for me to emerge. Mum is reading; Vanessa has wandered outside and is doing handstands on a patch of grass near a bed of bright canna lilies; Dad is smoking and staring at the ceiling.

Our letters are censored, clumsily torn open and read by the greasy-fingered immigration officials at the post office, so that by the time we get them, they are smudged and fingerprinted and rumpled and smell of fried fish, Coke’ n’ buns, and fried potato chips: the office food of Africa. We may make phone calls only when the operator at Liwonde is on duty so that our calls can be monitored. If the operator is taking the rest of the day off, or is at home with malaria, or if the operator is attending a funeral, we cannot make a phone call.

I do not remember anyone making or receiving a phone call in that house. The Liwonde operator and his family appeared to suffer the most unfortunate ill health.

Butchery

TOUCHING

THE GROUND

Mgodi Estate is set up on gently sloping, sandy soil, seeping into the horizon, where a yellowing haze hanging over Lake Chilwa (less a lake than a large, mosquito-breeding swamp) marks the end of the farm and the beginning of the fishermen and their dugout canoes and their low, smoking fires over which they have stretched the gutted bodies of fish (spread thin, like large irregular dinner plates). From the spot where our garden ends (which Mum immediately encloses within a grass fence), the bodies start, and stretch as far as you can see on any side. Wherever we drive in Malawi there are people, and people in the act of creating food, whether scratching into the red soil with hoes and seed or raking the lakes for fish. It doesn’t seem possible that there can be enough air for all the upturned mouths. The land bleeds red and eroding when it rains, staggering and sliding under the weight of all the prying, cultivating fingers.

Our house is big, airy, well-designed, and cool, with a mock Spanish grandeur that holds up only under fleeting scrutiny. Arches and a gauzed veranda surround the house; a large sitting room, a dining room, a passage down which there are three bedrooms and (unheard-of luxury!) two bathrooms. The kitchen, dominated by a massive woodstove and a deep sink, is set in a little cement hut behind the house where its heat and smoke can be contained. Our cook is a gentle, avuncular Muslim called Doud whose careful rhythm of prayer and cooking and cleaning washes like a balm from his small inferno behind the dining room and soothes in waves across our house. The floors are covered with shiny, peeling-in-places linoleum, and the made-on-the-farm doors and cupboards have swollen in the humidity and must be forced into their holes. Termites and lizards have set up house on the walls.

The large garden is thick with mango trees and is a sanctuary for birds, snakes, and the massive black and yellow four- to six-foot-long monitor lizards. There is a swimming pool and a fishpond behind the house, but these bodies of water are a stubborn, frothing, seething mess of algae in which monitor lizards float, their small faces hiding their large, hanging bodies, and in which there are scorpions and frogs in staggering numbers. There is still the occasional goldfish, from previous managers, hanging in the murky fishpond, but between the monitor lizards and the fishing birds, their numbers dwindle monthly.

Dad strides down the passage in the morning, when the sun is just beginning to finger the skyline, banging first on my door—“Rise and shine!”—and then on Vanessa’s on his way to the veranda where Doud has set tea and fresh biscuits on a tray. Vanessa and I each have two beds in our rooms. Vanessa has taken the mattress off her spare bed and has laid it up against her door to dampen Dad’s early-morning wake-up calls and to ensure that when she doesn’t appear for tea he can’t come crashing into her room shouting in blustery, sergeant-major tones, “C’ mon, rise and shine. What’s wrong with you? Beautiful day!”

Mum and I both work on the farm. Mum walks down to the grading shed (a massive hangarlike structure, into which all the tobacco from the farm has been brought) during the reaping season, or is driven down to the nursery where tobacco seedlings strive under the heat during the planting season.

Mum had been issued a motorbike, but after her first lesson ended (with a humiliating burst of feathers from a surprised guinea fowl) in a flower bed, she turned the motorbike over to me and either relied on me to drive her down to the tobacco seedlings, or walked, with the dogs fanning out in a destructive, chicken-killing wake behind her. There were constant requests from Malawians, toting bloodied fowl, for “compensation for chicken death.” We began to suspect that even Mum’s badly behaved dogs could not possibly have the energy (in the thick, swampy heat that hung almost permanently over the farm) to kill such a number of chickens and ducks over such a wide, diverse range (and all, apparently, within an hour or two). But we always paid up.

There was a constant, unspoken tension in the air, expressing the Malawian’s superiority over all other races in the country. Even Europeans who had been in Malawi for generations, and who held Malawian passports, were on permanent notice. A complaint from a disgruntled worker could have a foreigner (regardless of citizenship) thrown out of the country immediately and forever.

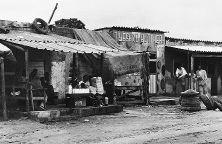

At the end of the farm, where the road bordered the beginning of the fishing villages, and all through the country, there were the blank faces of elaborately fronted, abandoned Indian stores whose owners had been unceremoniously expelled from the country as unpopular, money-grubbing foreigners. The stores had been handed over to Malawians, who soon lost interest in the long hours and careful scrutiny that are required to make a living from selling small bolts of cloth, single sticks of cigarettes, and individual sweets to an impoverished population. Now the windowless stores baked in the sun, their previously brightly painted walls bleaching, their floors littered with the droppings of fowl and birds, their rafters hung with bats and caked with the crusty red tunnels of termites.

Pulling dugout canoe

I often ride the motorbike down to these abandoned stores, which are so hung about with ghosts and old dreams and a lost time. Sometimes, I see chickens scratching on the cracking concrete floors where once a tailor toiled strips of bright cloth through his fingers to the treadle of a Singer sewing machine. This is as close as I get to the swamp. From here, I sometimes see men, stripped to the waist, their backs silver-shiny with sweat, as they pull dugout canoes (made farther and farther from the lake as forests disappear into stumped scrubland in the wake of many busy axes) to the lake. The men sing as they pull the craft; their song is rhythmic and hypnotic, like a mantra.

But mostly I don’t have time to drive all the way down to the start of the swamp. I have to work. Dad says, “You can’t have a vehicle unless you use it for farm business.”

I leave the house after tea in the morning; I come home for lunch and then leave again until supper. My arms and legs grow muscled and brown as I manhandle the Honda through thick sand (which quickly turns to impassable mud in the sudden, violent rainstorms that sweep across the farm). I ride the avenues between the one thousand plots that make up Mgodi Estate. I am supposed to make sure that the tobacco has been planted with appropriate spaces, that the crop is weeded, that the plants are topped and reaped correctly.

It’s a long time past lunch and I have been stuck at the north end of the estate since mid-morning trying to persuade the Honda out of an abandoned well into which I fell while following the flight of a fish eagle. Now I am hurrying down the avenues, keeping half an eye on the tobacco crop, half an eye on the road, where chickens and children and dogs have settled in the shade cast by straw barns and mud huts. Suddenly, a child runs laugh-crying from a hut, arms outstretched, looking over his shoulder at his mother, who emerges just in time to see the child hit the motorbike side on. I am sent sprawling, the vehicle’s spinning wheels kicking up stinging sand into my eyes and face until it stalls. In the sudden, ringing silence, I scramble to my feet, spitting dirt from my mouth and wiping my eyes. I am dizzy with fright, but the child is still standing and unhurt. He is looking at me with astonishment, his arms still outstretched. His face trembles, his lip shakes, and then he starts to cry. His mother swoops up on us and scoops her son into her arms. She shifts a smaller sling of baby, a quiet bulge in a bright hammock of cloth, under her arm to make room for the bigger child. The baby bleats once and then is quiet again.

I stand up and pull the motorbike up. “Are you okay?”

She shrugs and smiles. The boy nestles into the soft crease of her neck and calms himself with soft, diminishing sobs.

“

Pepani, pepani.

I’m so sorry,” I say. “I didn’t see him. Is he okay?”

The woman shrugs and smiles again and I realize that she does not speak English. I have only learned a few phrases of Chnyanja, none of which (“Thank you”; “How are you?”; “I am fine”; “What is the name of your father?”) seem appropriate for my current predicament.

I put my right hand to my heart and bob a curtsy, right knee tucked behind left knee, in the traditional way, to reinforce my apology. The woman looks uneasy; she pats her young son’s head almost as a reflex and glances, as if for help, into the shadows under the drying crop of tobacco hanging in a long, low shed next to her hut.

“It’s no problem, madam,” a man’s soft voice says from the shadows. I shade my eyes against the harsh, blanching sun. There, under the cool, damp leaves, lying on a reed mat, is a man lying almost naked, with a young boy of twelve or thirteen, also hardly clothed, by his side. For a moment I am too surprised to reply. The man, obviously the father of the toddler into whom I have just crashed, props himself up on one elbow and rubs his bare, pale-shining collar bone with the thick fingers of one hand. The boy at his side stirs, rolls over, and hangs an arm over the older man’s neck, his face stretched up in a grimace which is half-smile, half-yawn. The boy’s shorts have worn through at the crotch and his member is exposed, flaccid and long against his thigh.

The man begins to softly caress the boy’s arm, almost absentmindedly, as if the arm draped around his neck were a pet snake. I am suddenly aware of how softly quiet the hot afternoon is: a slight buzzing of insects, a crackle of heat from the drying thatch that covers the barn and house, the distant cry of a cockerel clearing his throat to warn of the coming of mid-afternoon when work will resume. My stomach growls, empty-acid. I feel the sun burning the back of my neck, my eyes stinging, my muscles aching. I pull the motorbike up and have begun to climb back onto it when the man suddenly pulls himself off the mat, the child still hanging from his neck.

The man is smiling. I see now that he is much older than I had first thought. I also see that the boy around his neck is disabled; he is a combination of helplessness (his arms and legs are as thin as bones and devoid of muscles) and of uncontrollable, rigid spasms, which send him backward against the softly restraining cradle of his father’s arms. His head rolls, his mouth sags open sideways, and saliva hangs to his chin. He makes soft, puppy noises. I have never seen this, an African child in this condition. It comes to me, in one sweep, that most children like this boy are probably allowed to die, or are unable to survive in the conditions into which they are born.

The man says, “Are you fine?”

I nod. “Thank you.”

He frowns and points at the sun with the flat of his hand, which also supports his son’s head. “You are out now? In this hot sun? You can see from the sun that it is time to rest.”

I nod again. “I was stuck.” I point to the motorbike. “I fell in a well.”

“Ah.” The man laughs. “Yes, that is difficult.”

“I’m sorry,” I say—I indicate the toddler, embarrassed in case the man thinks I am apologizing for his older, disabled child. I quickly add, “I didn’t see your baby.”

“Baby?”

“Your small boy.”

“Ah, yes. I see. We also have a baby, you see.”

“Yes. Big family,” I tell him.

“Lowani,”

says the man suddenly.

I grin and blink. “What? I don’t speak Chnyanja,” I tell him.

“Come inside,” says the man in English. He speaks quickly to his wife in Chnyanja and she disappears into the hut. “Please, we have some food. You must take your lunch here.”

I hesitate, torn between lies (“I’ve already eaten”; “They’ll be waiting for me at home”) and an impulse to please this man, to make up for the disruption and the accident. I nod and smile. “Thank you. I am hungry.”

And this is how I am almost fourteen years old before I am formally invited into the home of a black African to share food. This is not the same as coming uninvited into Africans’ homes, which I have done many times. As a much younger child, I would often eat with my exasperated nannies at the compound (permanently hungry and always demanding), and I had sometimes gone into the laborers’ huts with my mother if she was attending someone too sick to come to the house for treatment. I had ridden horses and bikes and motorbikes through the compounds of the places we had lived, snatching at the flashes of life that were revealed to me before doors were quickly closed, children hidden behind skirts, intimacy swallowed by cloth.