Dragons & Butterflies: Sentenced to Die, Choosing to Live (67 page)

Read Dragons & Butterflies: Sentenced to Die, Choosing to Live Online

Authors: Shani Krebs

Tags: #Thai, #prison, #Memoir, #South Africa

I’d noticed that the overhead fan in Mohammed’s house was broken, and one of the first things I planned to do was get the electrician in and have it replaced. Things were going smoothly and it felt great to be out of solitary confinement. After months in shackles, though, I was struggling to walk and my knees were giving me a lot of trouble. For some months I’d also been having a lot of toothache, and at the end of August I finally got to see the prison dentist. I hadn’t been for a dental checkup for over eight years. I had heard the horror stories about how prison dentists used a hammer and chisel if they had difficulty pulling a tooth out, not that I really believed them. But I had always been terrified of the dentist, so stories like this didn’t help my nerves. Twenty-two of us were ordered to line up outside the dentist’s room. I was the 19th person in the queue, and I can tell you my hands were sweating. But it was amazing. The whole thing was practically painless. I didn’t even feel the injection. Each prisoner got his anaesthetic with a new syringe and needle. As one person came out, so the next person followed. The whole tooth-pulling process took hardly any time at all. Imagine – 20 people having teeth pulled out in 25 minutes flat. Now that should be one for

Guinness Book of Records

!

Mohammed had given me his lockers next to the bakery, which meant that I now had three lockers there. He had also asked me to burn all his letters and documents. While I was doing this, I came across a letter from the Iranian embassy supporting his royal pardon submission. I kept it in order one day to show the world how supportive other countries were of their prisoners, in comparison to the South African government. After reading Mohammed’s support letter, I realised how unlikely it was that I would be granted a royal pardon without something similar from the South African embassy. I decided I would do my best to stay positive, if only for my sister’s sake, and patiently await the day that I would eventually be released. I was not counting on anybody intervening. In fact, I was expecting to stay in prison for many more years. Joan wanted to hire a Thai lawyer to follow my royal pardon application and apply some pressure, but I was dead against this. In my experience, Thai lawyers were corrupt and crooked. Firstly, they charged a ridiculous fee and, secondly, they could deliberately jeopardise your chances. The lawyer my sister had contacted had already made her all kinds of promises. If your application was rejected, he told her, he knew somebody in the Royal Palace and that, second time round, a royal pardon was guaranteed. I told Joan that I would rather donate the money to the King’s charity, and anyway, according to the embassy, my application was already at the Palace.

Round about this time, the Department of Corrections adopted a new policy. Anybody with less than a life sentence was to be moved to prisons in the provinces. One such place where foreigners were going to go was a prison called Klong Pai. It was situated in a valley with a great view in the middle of nowhere, approximately 600km out of Bangkok. In comparison to Bangkwang, apparently it was hell. A lot of Asian foreigners got transferred there, and saying goodbye to our friends, knowing we would probably never see them again, was really hard.

When we heard about this new policy, I immediately wrote to the embassy, asking them to write in turn to the Department of Corrections to ask them not to move us. Apart from anything else, the distance from Bangkok would make it difficult for anybody to visit the foreign prisoners.

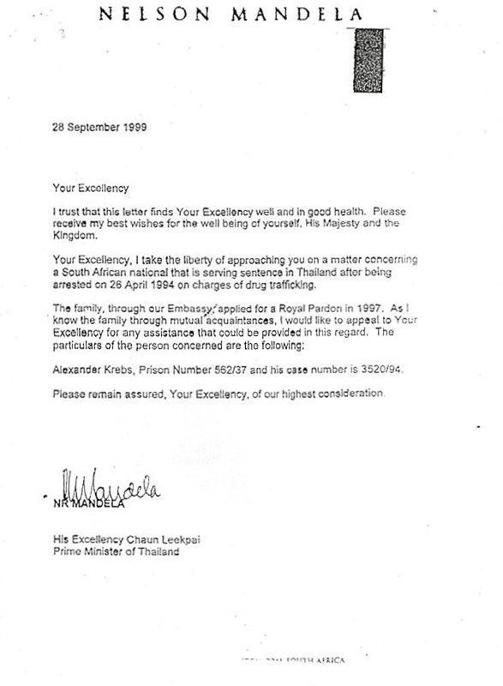

In April 1999 Nelson Mandela had stepped down as the first democratically elected president of South Africa, and in June of that year Thabo Mbeki took over the reins. I had a brilliant idea. Businessman and philanthropist Bertie Lubner, who was already actively engaged with my case back home, and was being an incredible help to my sister in her efforts, was a personal friend of Mandela’s. Through Bertie I thought I would try to get Mandela to twist Mbeki’s arm to write a letter of support for me. It was a faint hope, and deep down I knew it. I don’t really know what I was thinking. Who was I, anyway? All I had done was send my own long letter to the great statesman and paint his portrait. I

had

heard that the portrait hung on a wall in President Mandela’s house, and I also knew that my letter had been put into his hands, thanks to Bertie. I realised that a letter of endorsement from the new South African president was a long shot, and that a letter from Mandela himself was an even longer one. I was wrong on the first count, but not on the second.

In order for me to be creative, I need some sort of a routine, and since my return to Building 2, I had had no desire to draw. Instead, every day I would spend hours walking. I knew I would get back to my art but I wasn’t ready yet. In the meantime, I arranged, for 2 000 Thai baht, for the carpenter to build me a table with one big sliding drawer and a locker on the side. Because he could only do odd jobs on the weekend, it was going to take a month, but this suited me fine. I moved into my new house. The old man welcomed me, but at first he was not very friendly. With time, however, and as we got to know each other, we became like family.

While I was in solitary I had painted about 50 pictures, all of them on A4-size paper because of the lack of space. Everything had seemed confined and restricted – probably because it was. Even the imagination has its boundaries, I suppose. Now that I was in a different space and felt freer to move around, I ordered A2 paper.

A woman by the name of Norma, who helped and supported some of the ladies at the women’s prison, came to visit me, and she offered to take my paintings back to South Africa. She was a godsend and a true Christian, and I couldn’t have been more grateful. I was constantly amazed at how helpful people were to me.

When I got out of solitary, there was a new foreigner in Building 2. He was an F-16 jet fighter mechanic from Norway and we became instant friends. Kjell was well over six foot tall and looked like an American footballer. He had been arrested in November 1987 for purchasing about 55 ‘muscle-growth’ pills, which turned out to be a drug called

yaba

(basically methamphetamine mixed with caffeine). He was sentenced to 33 years. Around February/March of 1988, the Norwegian foreign and justice ministers came to Thailand to negotiate a prisoner transfer treaty. They even visited my friend in Lard Yao prison, where he was being held. In June 1988 his prime minister came to sign the treaty. All this took place within a period of seven months. Denmark had also entered into a treaty with Thailand, and Sweden had also signed one. When I heard these stories it was hard not to feel bitter.

On 15 October 1999 I turned 40. It was my sixth birthday in prison.

My brother-in-law always said life begins at 40, but I don’t know about that. To me it sounded quite old. Nevertheless I felt strong and fit. I weighed 80kg, I didn’t smoke and I had given up drugs. I might have been getting older but my life had also taken a turn for the better.

During one of the embassy visits, I’d expressed a concern to the consular officer about how, in the impending 1999 amnesty to celebrate the King’s birthday in December, if drug cases were cut by half, my sentence would be reduced from 40 years to 20. But this would mean that I would be transferred back to the Klong Prem prison complex, and put in Lard Yao, the section that held prisoners with short sentences. I did not want to go there, I told her. Lard Yao was like the Wild West, something my Norwegian friend had confirmed in the conversations we’d had. Fights were part of everyday life there and one could easily kill somebody or be killed. If this happened, it would mean another life sentence for me. I told her that I needed the embassy’s assistance to make sure I was not transferred there.

After what I had thought was a reasonable and logical conversation between us, the consular officer went and reported me to Foreign Affairs, telling them that I had threatened to kill the embassy staff in Bangkok. Talk about a miscommunication! You would think the embassy had more important stuff to deal with, like concentrating their efforts on working towards a treaty with Thailand. I had to defend myself and to clarify what I had actually said and the reasons I’d had for saying it, so I wrote a lengthy letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, which began as follows:

Dear Sir

It was with much concern that it has come to my notice that certain allegations have been made against my person by your Bangkwang staff to third parties. It is my strong hope that the underlying cause is based on a misunderstanding, as otherwise the innuendo that I would blackmail the South African Government by threatening to commit a murder unless I was helped by the Government, would be quite shocking. Particularly for argument’s sake, if I did have such violent intentions, what would it really benefit me? It would seem that the person who is the originator of this slander must have read too many detective novels. You can rest assured that I am not a violent person and wish to be taken as such. Hereunder I would like to acquaint you with what was really said and which was subsequently twisted and quoted out of context …

I took the opportunity to say a whole lot more, repeating many of the pleas I had made so many times before about the conditions for foreigners in Thai prisons and about the treatment we received. I made a number of very clear and reasonable proposals, among other things, regarding the frequency of embassy visits (which had now been cut back from monthly to only three times a year), medical assistance, pastoral care, the daily allowance for prisoners and the seemingly stalled prisoner transfer treaty between South Africa and Thailand. I held up for comparison what other countries were doing for their citizens.

Needless to say, I didn’t receive any reply. Everything we tried fell on deaf ears. I think the furthest my letters got was probably into the nearest dustbin, but I refused to give up. It was a sad state of affairs that the fate of South African prisoners in Thailand remained an unsolved matter.

My sister had managed to raise enough money for me to buy Mohammed’s house. Bertie Lubner, along with Dennis Levy from the Chevra Kadisha, had contributed towards this. I was discovering what a shrewd businessman Mohammed was. He had been playing with everybody’s money. One of the missionaries who used to visit the prison, whose name was Cosmos, had lent Mohammed 30 000 Thai baht. After he had been released from Bangkwang, and while he was awaiting deportation, Cosmos went to visit Mohammed, who told him about our deal. He also told Cosmos that I would settle the 30-grand debt. Back in the prison, I sold the foreign currency to one of the Chinese, which enabled me to settle some of my friend’s debts, but not all of them. One of Mohammed’s closest friends was a guy named Chuka, to whom he owed 24 000 Thai baht. Mohammed had not included Chuka’s name on the list of people I had to pay, and there were others. In fact, Mohammed left me with a huge headache. Everything he left me cost me more than if I had bought it from someone else. Cosmos came to visit me to discuss the debt. I told him I was sorry, but I couldn’t pay him. Mohammed just had too many debts inside the prison, and these were guys I had to live with and whose faces I saw every day. It was not right that Mohammed had ripped them off, but paying them first was the decent thing to do. I told Cosmos my hands were tied. Being the gentleman that he was, Cosmos saw my dilemma and he accepted the situation. In the meantime, I tried my best to settle each person’s debt, even if I settled only part of it. Some I couldn’t pay at all, but, as everyone in prison knows, that’s a risk you take when you lend money.