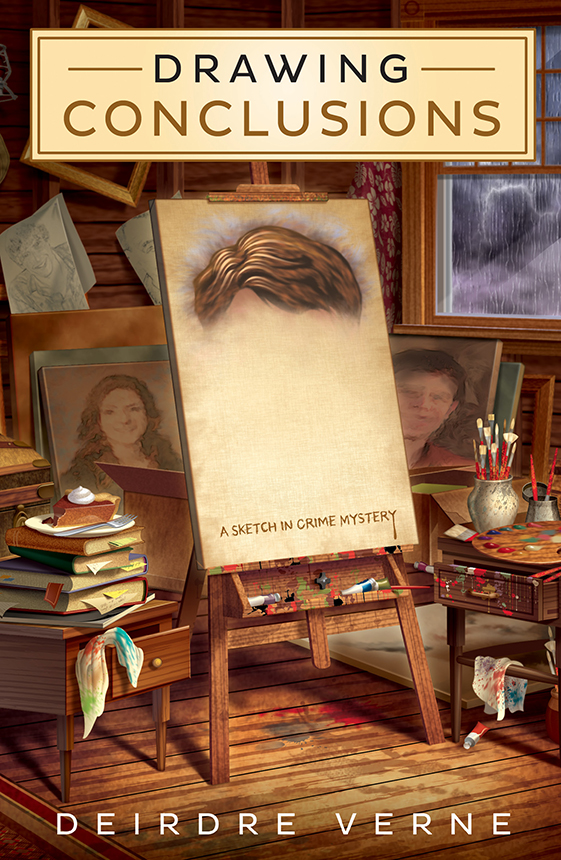

Drawing Conclusions

Read Drawing Conclusions Online

Authors: Deirdre Verne

Tags: #mystery, #mystery fiction, #long island, #new york, #nyc, #heiress, #freegan, #dumpster, #sketch, #sketching, #art, #artist, #drawing

Copyright Information

Drawing Conclusions

© 2015 by Deirdre Verne.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Midnight Ink, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author's copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First e-book edition © 2015

E-book ISBN: 9780738743424

Cover illustration by Bill Bruning/Deborah Wolfe Ltd

Cover design by Kevin R. Brown

Editing by Nicole Nugent

Midnight Ink is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Midnight Ink does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher's website for links to current author websites.

Midnight Ink

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.midnightinkbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dedication

For Peter and Mats. Whatever it is, stick with it.

Acknowledgments

After reading my umpteenth mystery novel, I was convinced I could write my own. Come to find out, I had a long way to go. Thankfully, my moment of inspiration led me to a wonderful group of supporters who educated and guided me through the process.

To Gay Walley, my first literary friend: I never had more energy than climbing the stairs of your fourth floor walk-up. It was worth every step.

To Terrie Farley Moran and my pals at the New York Chapter of Sisters in Crime: if not for the monthly meetings, my manuscript would still be in a drawer.

To Victoria Skurnick and the team at Levine Greenberg Rostan Literary Agency: thank you for taking a chance on a newcomer to the industry.

To Terri Bischoff, Beth Hanson, Nicole Nugent, and my fellow writers at Midnight Ink Publishing: what a wonderful introduction to the world of publishing.

To Sue and Bob, my first fans, and my patient family: thank you for giving me the time and support to write through to “The End.”

one

Charlie balanced the ladder

at the base of the first Dumpster and yanked open the lid with a crowbar. He jammed a wooden wedge into the joint. Then he gave the metal lid a hardy slap to ensure it wouldn't accidentally slip and decapitate us.

“Okay, coast is clear,” I said. “Let's suit up.” I pushed up the sleeves of my hoodie and handed Charlie a box of surgical gloves, snapping on a pair for myself.

“You're up for the first dive, CeCe,” he said. “Let me hear the Freegan motto.”

“

If it moves, stop, drop, and run

,” I said, placing my foot on the first rung of the ladder.

“That's what she said.”

“You're a pig. Hand me the flashlight.”

I steadied the ladder and swung one leg over the edge. Then I clipped the flashlight to the corner of the bin for a quick look-see.

“Good stuff,” I said, passing a drippy egg carton to Charlie. “A few are broken but I can scramble and freeze them raw.” A surge of adrenalin pumped toward my heart as I reached down into a pile of nearly fresh vegetables. It amazed me that after all these years of foraging for discarded food, I still got a high out of the hunt. This was a quality I shared with others in the Freegan movement. Freegans aren't necessarily poor or destitute; they simply dislike waste. I was willing to ignore the seeping smell of rot accelerated by the warming spring weather if the food could be put to good use.

“There's got to be ten pounds of bacon still in the wrapper. Prep the cooler.”

“Trina and Jonathan asked for bagels and lox,” Charlie reminded me. “See what you can do.”

“Easy pickings,” I replied. “There must have been at least three bar mitzvahs today.” I threw a bag of bagels over the edge and shoved an industrial-sized carton of cream cheese into my sack. I pointed my flashlight toward the back of the Dumpster. It was full to the brim.

“Tomorrow I'll call the catering manager and connect him with the food pantry. This is a shame.”

“We have room in the Gremlin,” Charlie said. “Let's do a drop at the pantry in the morning.”

I looked at the Gremlin. The car was older than me. I'd rescued it from the town dump and was determined to drive it until it stopped. I wasn't sure I would make a great impression chugging up to the food pantry with a hatchback full of discarded food.

“They'll never take it. It's been sitting around too long, and we're not the original source.”

“Too bad,” Charlie said. “Keep digging.”

I had my hand on a half-eaten aluminum tray of baked ziti when my ears perked up.

“Shit,” I said as I popped my head over the rim of the Dumpster. “I hear something.”

“Me too. Kill the light,” Charlie said. He scrambled up the ladder and jumped into the bin for cover.

“Sounded like the bleep right before a siren,” I whispered, my feet sinking into the moist refuse. I reached for Charlie's gloved hand.

“Do you think someone reported us?” he said as he squeezed my palm. The hum of a car engine reverberated along the walls of the metal Dumpster. With the lid open only a few inches, the sour stench became oppressive. I ran my hand under my nose to diffuse the odors.

“I think it stopped,” I said and then added, “The police probably aren't interested in arresting two peace-loving Freegans repurposing day-old bread. What would they book us on?”

“How about âwillful consumption of post-dated food'?”

“Funny. What about âpremeditated attempt to lower the carbon footprint'?”

“Nice, CeCe.”

With our eyes peering over the edge of the Dumpster, we watched the tail end of a police car cruise by. “Wonder where he's headed?” I said as I searched out Charlie's face in the dark. “I'm a little freaked.”

Charlie exhaled slowly. “Why does this always feel so wrong when all we're taking is something no one else wants?”

“Because we've been conditioned to purchase food from a shelf in a store.”

“There's something appealing about that scenario,” Charlie laughed.

“I know,” I said looking down at my shoes. “I've ruined more sneakers this way.”

“Let's go barefoot next time.”

“I'd rather convert to consumerism,” I said, climbing out of the Dumpster. “Let's get out of here.”

“My thoughts exactly,” Charlie agreed. “Grab the ziti. I'm starving.” We hurriedly packed the food and drove out of the catering hall's parking lot with our lights off as an extra precaution.

“I'm sticking to main roads,” I said. “The street lights make me feel safe. Is that lame?”

“Not to the guy who invented the night-light,” Charlie replied.

“I never had a night-light.”

“That's because you had Teddy,” Charlie answered. “How many little girls have the convenience of a fraternal twin in the upper bunk?”

It was true. My brother had a way of making people feel safe even as a kid. It was no surprise he became a doctor.

“We did share a room for a frighteningly long time,” I said. “If I remember correctly, you spent a fair share of nights in your Elmo sleeping bag on our floor to be close to your best friend.”

“I loved that fuzzy red dude.”

“I'm talking about Teddy not Elmo,” I corrected Charlie.

“I love that dude too.”

Charlie and I drove slowly back to the hamlet of Cold Spring Harbor, only a few miles northwest of the catering hall we had just pillaged. The moon hung low in the sky, illuminating the fan of interconnecting inlets that littered the North Shore of Long Island. The narrow roads were crowded by early-blooming forsythia bushes, the gaps in foliage indicating the understated entrances to the old monied estates. With the windows rolled down, the clean scent cleared my nostrils and any hint of our Dumpster diving was contained in well-secured plastic bags. Like a beacon of safety, a light shone in the widow's peak of the harbor master's home. My home. Charlie, Trina, Jonathan, and Becky's home, as well as a smattering of cats, dogs, goats, chickens, and the random hiker. As luck would have it, the first settler in my family's long lineage was the original harbor master on the North Shore of Long Island. For well over a century, generations of my family skillfully guided schooners and barges toward the isle of Manhattan to exchange their goods.

I inherited the defunct Harbor House with its oddball layout, rotting sills, and dirt-floor basement at the age of twenty-one. My family considered it the throwaway component of my much larger trust. I saw it as an opportunity to live an unconventional life off the grid with my equally committed green friends. It was an ideal existence for five twenty-somethings experimenting with organic farming and subsistence living.

“Hey, all the lights are on,” I said. “Every damn one. That's going to cost us some money.”

“Maybe they were hungry enough to wait up for us,” Charlie said.

We turned onto Shore Road and were welcomed by two cars in the driveway. Now I knew where the police were headed.

“Crap.” Charlie was halfway out of the car before I put it into park. “CeCe, are all the farming permits in place?”

“The permits are fine. It's the alternative farming I'm concerned about.”

Charlie came to a complete halt, turned 180 degrees, and made a beeline for the car. I grabbed his arm for an awkward do-si-do.

“Chill,” I said. “I'm pretty sure you smoked the evidence last night.” I couldn't actually say it

wasn't

a drug bust. However, this seemed to be missing the element of surprise and the pack of hyped-up dogs that can sniff out an aspirin wedged under a car seat.

“We should call Teddy,” Charlie said, his eyes darting desperately from side to side.

“Come on,” I urged Charlie as we headed toward the house.

Trina, Jonathan, and Becky were sitting at the kitchen farm table. In the various corners and cubbies of the room, cops filled in spaces like spare furniture. The room murmured with a sea of coughs and grumbles.

“Constance Prentice?” A broad-shouldered man reached out to shake my hand. He had thick dark hair like my brother and the same commanding presence. “I need a moment in private.”

Charlie was glued to my back, a second skin. I rotated my head and mouthed what he and I were both thinking. There was only one person we both knew with enough clout to upend the local police department in the middle of the night: my father.

The venerable Dr. William Prentice was the founder and lead scientist of Sound View Laboratories, the central clearing house for all things DNA in the United States and around the globe. It was the home of the double helix, the national genome project, and a slew of other international scientific studies. In the world of hard-core science, it was hard to get bigger than Dr. William Prentice, a man who had devoted nearly fifty years to searching for the cure. Which cure? Who cares. Take your pick. From what little I understood (or wanted to) about DNA, once those elusive little genomes were trapped and mapped, the answer would tumble out and wrap itself around a prescription bottle with a child-safety lid fully intact.

I turned to the officer and considered his face. Familiar, serious, concerned. For a second I thought maybe we had already met, and then I realized he wore a mask of compassion. A face practiced in delivering bad news. If he assessed my face, I'm sure he was confused. Indifference usually does not precede the announcement of a parent's death. I was, however, the black sheep of the family. My father despised my bohemian lifestyle, hence our decade-long estrangement.

“Officer, I'm assuming something has happened to my father.” My tone was flat.

“No, but we need to speak to you and your housemates about your brother,” he said pulling a chair out for me.

“Teddy?” I said, pushing the chair back in place.

“I'm sorry but I have some unfortunate news,” he said, offering me a seat a second time.

My ears rung like a warped tuning rod, the pitch escalating until I could barely decipher the officer's words. “Your brother, Dr. Theodore Prentice, has passed away.”

I looked helplessly at Trina and Jonathan, but I could tell by their grave expressions that I had heard the officer correctly.

My beloved twin brother, Teddy, was dead.