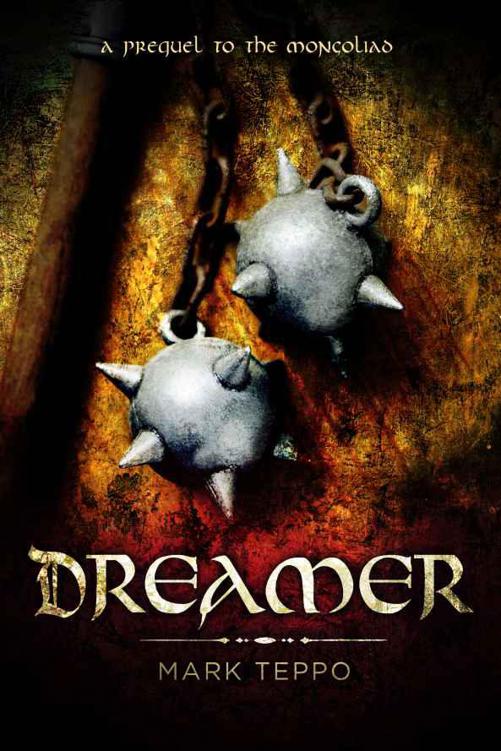

Dreamer: A Prequel to the Mongoliad (The Foreworld Saga)

Read Dreamer: A Prequel to the Mongoliad (The Foreworld Saga) Online

Authors: Mark Teppo

A TALE OF FOREWORLD

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2012 by FOREWORLD LLC

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by 47North

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

eISBN: 9781611096354

A TALE OF FOREWORLD

MARK TEPPO

Dominus

det tibi pacem.

— Personal greeting of Francis

of Assisi

T

he

oratory and two other buildings of the hermitage were built along a ridge of

mottled rock near the peak of La Verna. The upthrust of smooth basalt served as

the back wall for one of the two dormitories. A small garden was delineated by

a hedge of jumbled stones, a makeshift barrier that mainly served to keep the

capricious wind from stealing the soil. Several goats and chickens wandered

aimlessly about the grounds — the goats, with their thick coats, were not

terribly disturbed by the wind that blew through the rocky terrain of the

mountaintop.

The

hermitage was home to a half dozen lay brothers of the

Ordo Fratrum Minorum

—

Fraticelli

, as they referred to themselves. The mountain had been a

gift from the Count of Chiusi, who had, some years prior, been witness to one

of the spontaneous sermons offered by the titular head of the order, Francis of

Assisi. So impressed by Francis’s rhetoric, he had bequeathed the territory on

the spot.

It is a barren place, La Verna

, he had said to Francis,

and

once you climb past the thick forest that cloaks the lower portion of the

mountain, there is little to sustain a man among the naked rocks of the peak.

To

many, this gift would have been an insulting bequest, but Francis of Assisi and

his

Fraticelli

had a relationship with God that eschewed property and

goods — in that sense, the hermitage atop La Verna suited them perfectly. Other

than the buildings themselves, which had been constructed by local tradesmen at

the command of the count, there was nothing of value atop the mountain. The

view — a dizzying panoramic of the Tuscan countryside — was impressive, and a

constant reminder of the sublime beauty of God’s handiwork, but it was ephemeral.

Pilgrims marveled at the vista, and some even attempted to capture the enormity

of the landscape in song and art, but for the local people who lived down in

the valley, a hike to the top of La Verna did not aid them in their daily

labors. They might return refreshed of spirit, but their hands would be empty.

Unlike the

Fraticelli

, they did not seek out such austerity; rather,

they struggled every day to escape from it.

The

Fraticelli

did not go down into the valley very often, nor did many

visitors brave the long hike. The only one who came with some regularity was

Piro, a wiry goatherd who habitually brought a meager assortment of supplies.

The odd time when Piro brought someone else with him was a cause for

celebration among the lay brothers. Simply because the monks eschewed owning

property and goods did not mean they did not enjoy a decent meal now and again,

and an increase in visitors meant a commensurate increase in fresh supplies

from the village below.

There

were several holy days that the monks celebrated, and around those days, the

Fraticelli

looked forward to Piro’s visit. On the morning before the Feast of the

Exaltation of the Cross, the monks began to find excuses to wander close to the

old pine tree that clung to the edge of the bluff. The upper half of the tree

had been blasted by lightning years before the monks had arrived, and it had

never offered them any shade, but it was both a notable landmark and a

convenient vantage point from which to observe the trail.

Brother

Leo, having been at the hermitage since its buildings had been erected, no

longer paid much attention to the younger brothers’ eagerness, but on this warm

September morning as he worked a hardscrabble area of the garden, he gradually

realized all of the monks were clustered around the tree. Brother Leo set aside

his hoe and joined the group, where he learned not only that had Piro been

sighted, but that he had a companion. The monks were engaged in a frenzy of

speculation as to the identity of the other visitor. Listening to them, Brother

Leo was reminded of the flocks of starlings that used to chatter in the shrubs

around the decrepit old building near the Rivo Torto, where he had first become

one of Francis’s followers.

The

sharp-eyed lay brothers — Cotsa and Nestor — had already determined that both

pilgrims carried satchels.

Brother

Leo listened to the prattle of the others with detached amusement. He had grown

accustomed to the serenity afforded by the seclusion of the hermitage; he did

not yearn as readily as these youngsters for these passing dalliances with the

decadences of civilization. Most of the lay brothers had only been following

the letter of Brother Francis’s Rule for less than a season. The mystery of an

unexpected visitor — and the possibility of extra rations! — made them

unbecomingly giddy. He could not fault them, however; he remembered the first

few years in the order — back before it had been officially recognized by the

Pope — and how any respite from strict piety was eagerly embraced.

“There,”

said Brother Cotsa. The tall monk pointed over the heads of the others, and all

chatter ceased as the

Fraticelli

turned their collective attention to

the path.

Piro

emerged from the cleft first, and he smiled and waved at the sight of the

clustered monks. “Ho, Piro,” Cotsa called down to him, and Brother Leo frowned

at his lay brother’s casual disregard for the order’s traditional greeting.

Some of the others shouted down to the pair as well, asking questions that

could not be readily answered before the two men arrived at the hermitage.

The

stranger paused as he emerged from the rocky passage, taking a moment to stare

up at the monks. A large hat, floppy from age and the heat, covered his head,

and his tunic and pants were equally simple and unadorned. His boots were worn

but solid — well-formed to his feet and legs. The man carried a sword on a

baldric, and he stood with the practiced ease of a man used to the presence of

a scabbard against his hip. His skin was darker than Brother Leo's, and his

face was adorned with a neatly trimmed beard. Brother Leo estimated he had not

seen more than two dozen winters, but there was a cant to his carriage that

suggested he carried both wisdom and pain beyond his years.

“May

the Lord give you peace,” Brother Leo called out to the stranger in Latin. He

glared at the

Fraticelli

next to him, silently admonishing them for

their failed courtesy.

The

stranger looked up, raising a hand to shield his eyes from the sun. “And may

peace be upon you as well,” he replied.

Brother

Leo scratched the side of his neck. The man had replied quickly and surely — his

Latin graceful, yet touched with an accent Brother Leo could not place. He

spoke as if the greeting of the

Ordo Fratrum Minorum

was familiar, but

his response was not quite in keeping with tradition.

Piro

reached the plateau and dumped his satchel on the dusty ground. “Ho, holy men,”

the young goatherd called out. “I bring one of your brothers.”

“One

of us?” Brother Mante asked. He was the tallest of the group, and oftentimes

his height made him the spokesperson. “How can that be, Piro? None of us carry

a sword.”

“He

has” — Piro offered a steadying hand to his companion who was struggling with

the last few steps up the steep path — “what do you call it?”

The

young man seized the offered hand and hauled himself up. “An

Ordo

,” he

explained. He fumbled with his satchel for a moment as if he wasn’t quite sure

what to do with his hands. “I am Raphael of Acre. Forgive my unexpected arrival.

Piro here said he would show me the way, and it would appear that he did so.

Quite successfully.” The young man was slightly out of breath, but he hid it

well.

“Which

order might you be a member of?” Brother Cotsa inquired, still brusque with an

indelicacy born of excitement.

“Perhaps

we might wait to interrogate our visitor until after he has rested from his

climb,” Brother Leo pointed out, mortified by the lack of decorum on the part

of his fellow

Fraticelli

.

“No,

no. It’s fine,” the young man said. “You are the

Ordo Fratrum Minorum

,

are you not? Followers of Francis of Assisi?” When several of the monks nodded

in response, he continued, “I belong to the

Ordo Militum Vindicis Intactae

.”

“See?”

Piro said, proud of his command of Latin. “

Ordo

.”

“No,

Piro,” Raphael said, laying a hand on his guide’s shoulder. “It’s not the same

thing.” He looked apologetically at the monks. “I am sorry for the confusion.

Piro has been very helpful, and I fear I may have inadvertently taken advantage

of his enthusiasm.”

“

Milites

,”

Brother Leo explained to Piro. “It means fighting men — soldiers.” He

translated the name. “Knights of the Virgin Defender,” he said, pointing at the

blade hanging off Raphael’s hip. “We are not Crusaders. We have no use for a

sharp tool such as that.”

Piro

scratched his head. “Crusader?” he asked, jerking a thumb at Raphael.

“The

Fifth?” Brother Mante blurted out.

“Aye,”

Raphael said. “That is the one.”

The

last Crusade, the Fifth, had ended a scant few years earlier. Already the word

from Rome was that it had been a failure and that another would be called soon.

Rome had no appetite for the continued presence of Muslim infidels in the

Levant. Raphael’s acknowledgment released a flood of questions from the monks,

and even Brother Leo found himself leaning forward to hear the young man’s

answers.

The Fifth Crusade! Could he have been in Egypt at the same time

as…?

Taken

aback by the enthusiasm of the

Fraticelli

, Raphael held up his hands to

quell the torrent of voices. “Yes,” he said, ducking his head in mild

embarrassment at the mix of confusion and fascination offered by the group of

monks. “Yes, I was at Damietta,” he admitted. “I was there when Francis came on

his mission to convert the Sultan, Al-Kamil.”