Dreamers of a New Day (25 page)

Read Dreamers of a New Day Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

One impetus behind the middle-class proposals for communal living, co-operative housekeeping and socialized services was what became known as ‘the servant problem’. This was particularly acute in high-waged America; between 1900 and 1920, the number of domestic servants in the US declined by half. The spread of domestic technology had been accompanied by rising standards of cleanliness, leading to an intensification of housework. Hence when the British writer G. K. Chesterton portrayed the home as an oasis of ease in 1927, Crystal Eastman responded irritably that it was not so for ‘home-keeping women’.

50

World War One resulted in a temporary panic in Britain about the lack of domestic servants, leading Clementina Black, in a memorandum to the Ministry of Reconstruction’s Women’s Advisory report on the

Domestic Service Problem

(1919), to suggest that ‘the best way of economising domestic service would be for a group of householders to establish a common centre for buying, preparing, and distributing food and for providing central heating and hot water.’

51

But as it turned out, R. Randal Phillips’s proposals for highly technologized homes in his book

The Servantless House

(1920) proved to be ahead of their time. British working-class women who had left domestic service for lucrative jobs in munitions would be forced back into service by unemployment during the 1920s.

Working-class women, both urban and rural, had their own problems of time. ‘Keeping house’ for them meant rising before dawn to light fires and prepare breakfasts, heating water for washing, stoking fires for baking, a ceaseless battle with dust and dirt, mending long into the night. During the 1880s ideas of a right to leisure were developing in the labour movement in both countries, as workers conflicted with employers over issues of time. This encouraged men as well as women to connect the hours of paid work with time spent on unpaid labour in the home. In 1885 the British trade unionist and co-operator Ben Jones

advocated ‘associated homes’, so as to make working-class women’s lives easier. Noting the arrival of sewing machines and wringing machines, he observed: ‘The fact of so many changes having occurred in domestic life, impels one to ask, Why should there not be others?’

52

Likewise Tom Mann, the socialist ‘New Unionist’ and advocate of the eight-hour day, argued in 1896 for ‘leisure for workmen’s wives’, in the popular magazine

Halfpenny Short Cuts

. Mann suggested the creation of co-operative groups for shopping, as well as a communal wash house and collective kitchen ‘thoroughly fitted with the best appliances’, as steps towards ‘Associated Homes’.

53

Hannah Mitchell was sceptical about all this talk, grumbling in

The Hard Way Up

that socialist men still expected their home-made meat pies like their reactionary fellows, and failed to understand ‘that meals do not come up through the table cloth’.

54

Despite her disenchantment with housework, she did recognize the implicit forms of co-operation which women developed among themselves, remembering with affection the women of the Midlands mining village of Newhall who imparted to her ‘the kind of knowledge one does not get from books . . . pickling, preserving, and making wines’.

55

But Mitchell did not see the creation of co-operative forms of housework as the answer to women’s domestic problems. Instead, like many other working-class socialist women, she was in favour of an extension of municipal services which she helped to initiate when she served on Manchester Council’s Baths Committees in the 1920s.

In both Britain and the US, socialist women, influenced by the German Marxists August Bebel and Clara Zetkin, imagined that in the socialist future housework tasks would be socialized and domestic labour reduced by technology. By the early 1900s dairying, making soap, candles, weaving, spinning and knitting had all entered the public sphere of manufacturing, while sewing, washing, ironing, nursing the sick, canning, preserving and baking also were becoming paid services or industrial activities. One wing of the socialist movement was inclined to see this as a capitalist invasion of the household, but domestic modernizers regarded the introduction of household technology as domesticity’s final knell. They believed the logic of capitalism would abolish housework.

The rebellious Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, whose wandering lifestyle was hardly conducive to housecraft, put her faith in technology in 1916:

The home of the future will eliminate the odd jobs that reduce it to a cluttered workshop today and electricity free the woman’s hand from methods antiquated in an era of machinery. There is no great credit attached to making a pie like mother used to make when a machine tended by five unskilled workers turns out 42,000 perfect pies a day! Cook stoves, washboards, and hand irons are doomed to follow the spinning wheel, candles and butter churns, into the museums, and few tears will be shed at their demise.

56

In 1927 Sylvia Pankhurst was equally enthusiastic about technology and electricity. She imagined that the hearth-brush and dishcloth would disappear, and meals would be produced from communal kitchens. Clearing up would be made easier by dishwashing machines and paper plates.

57

Unwittingly, the left libertarians Flynn and Pankhurst were heralds of the consumer revolution which would refuel twentieth-century capitalism.

A quite different approach was taken by the American socialist Josephine Conger-Kaneko, who insisted in 1913 that housework was work, and contributed to wealth:

You work ALL HOURS, at BOARD WAGES. That is, you get a part of the food you cook, and live in the house you keep, and you can have a dress occasionally that you make, FOR WORKING ENDLESS HOURS SO THAT YOUR HUSBAND MAY BE AN EFFICIENT WORKER FOR HIS EMPLOYER. . . .

THE UNPAID AND GROSSLY EXPLOITED LABOR OF MARRIED WOMEN IN THEIR HOMES MAKES IT POSSIBLE FOR THE EMPLOYER TO PILE-UP IMMENSE PROFITS OUT OF HIS BUSINESS, WHICH, OF COURSE, IS HIGHLY SATISFACTORY TO HIM.

But is it you, O Woman, who must pay the price?

58

Her theory that the housewife made an economic contribution to production by maintaining men, and as reproducers of new workers for capitalism, resurfaced in the American Communist Party during the 1930s as a demand for wages for housework.

Changing the sexual division of labour in the home was sporadically mooted. The suffrage movement contributed to an awareness of how gender inequality permeated everyday life in the home. In

Marriage as a Trade

(1912), the British feminist writer Cicely Hamilton stated that she could see ‘no reason why it should be the duty of the wife, rather than of the husband, to clean doorsteps, scrub floors, and do the family cooking. Men are just as capable as women of performing all these duties.’ Hamilton advocated passive resistance, concluding that the only way ‘woman can make herself more valued, and free herself from the necessity of performing duties for which she gets neither thanks nor payment’, was to ‘do as men have always done in such a situation – shirk the duties.’

59

Eight years on, Crystal Eastman was suggesting: ‘Perhaps we must cultivate or simulate a little of that highly prized helplessness ourselves.’

60

‘How can we change the nature of man,’ Eastman asked in the left-wing journal the

Liberator

in 1920, ‘so that he will honourably share the work and responsibility and thus make the home-making enterprise a song instead of a burden?’

61

She proposed rearing sons to accept housework – a somewhat uncertain and long-term solution. The weight of cultural expectation was still formidable. Nevertheless, by the 1920s a small group of American women with advanced views were proposing that men should share housework when women worked outside the home. In her article ‘Fifty-Fifty Wives’, Mary Alden Hopkins observed in 1923 that the problem was the differing attitudes men and women brought to domesticity. Women had to shed a sacrificial mentality.

62

In 1926 Suzanne La Follette complained that whereas work in the home was used as a reason for demanding shorter hours for women in industry, it was never expected that the husband should ‘share the wife’s traditional burden as she has been forced to share his. I have no doubt that innumerable husbands are doing this, but there is no expectation put upon them to do it, and those who do not are in no wise thought to shirk their duty to their families, as their wives would be thought to do if they neglected to perform the labour of the household.’

63

Educated middle-class American women who wanted work and married life were the first to experience the double burden which would continue to present modern women with painful choices between jobs and home. They were also the first women of their class to be drawn into the race against time. From the late 1890s, articles began appearing in women’s magazines about the terrible feeling of being in a rush which had seized American women. Urged to achieve the ‘House Beautiful’ yet pulled away from their homes by their clubs and charitable organizations, middle-class American women were depicted as being in a perpetual state of agitated haste. The middle-class housewife was in a cleft stick, for she was also being rebuked for not concerning herself with wider social issues outside the home. In

Increasing Home Efficiency

(1913), the Bruères upbraided women for ‘fluttering about inside four walls under the delusion that these mark the proper sphere of activity’.

64

Their advice was to rationalize housework in order to fulfil social duties in a wider sphere. Variations on the theme were the need to save time on housework in order to be creative outside the home, or to find ways of being creative about housework. Eunice Freeman in the

Colored American Magazine

proposed turning the home into a ‘gymnasium’ and seeing housework as a way of improving posture. Brooms, bedsteads, dusters and dishes could be transformed into ‘the apparatus by means of which the woman can make herself strong, erect, active and graceful’.

65

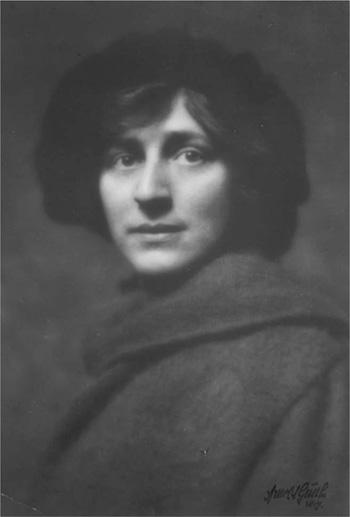

Crystal Eastman, ca 1910–1915, by Arnold Genthe (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University)

A less aerobic approach was outlined by Lillian Gilbreth, in her 1904

Management in the Home

. She recommended reducing the time spent on the tedious aspects of housework in order to spend more on its creative features and on childcare. This attitude to domestic activity became widespread after World War One. The home must be ‘a place in which we can express ourselves’, declared Gilbreth in 1927, in

The Home-Maker and Her Job

.

66

Re-making the home was linked to the reorganization of production, which was more advanced in the United States than in Britain. The first three decades of the twentieth century in America saw an intensive acceleration in the drive for even greater productivity. Lillian Gilbreth and her husband Frank were exponents of Frederick Taylor’s ideas of scientific management. Trained in industrial psychology, she applied Taylorist ideas of breaking down activities through time and motion studies, and increasing efficiency through ergonomic design. Human-centred domestic ergonomics resulted in kitchens in which everything lay within arm’s reach.

67

Christine Frederick was similarly enthusiastic about bringing the new ideas for increasing workplace productivity into the home. Frederick, who had acquired journalistic skills on the

Ladies’ Home Journal

, began her book

The New Housekeeping

(1916) with dramatic brio. ‘I was sitting by the library table, mending, while my husband and a business friend were talking, one evening about a year ago. . . . “What are you men talking about?” I interrupted. “I can’t help being interested, won’t you please tell me what efficiency is, Mr Watson? What were you saying about bricklaying?”’

68

And so, of course, a charmed Mr Watson explains to the enquiring darner how scientific management could be applied

in the home to speed up activities which had been governed by age-old customary practices. Frederick told housewives that if they applied scientific management’s drive for efficiency to domestic work, they could save not only time and energy, but also natural resources like fuel.