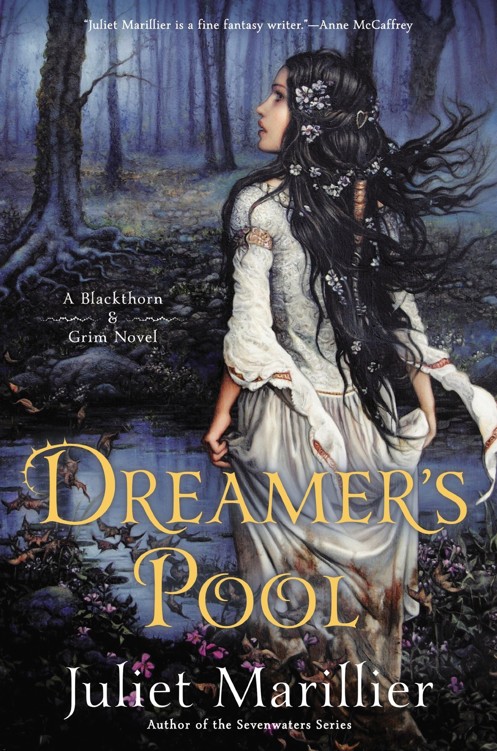

Dreamer's Pool

Authors: Juliet Marillier

About

Dreamer’s Pool

Embittered healer Blackthorn, wrongly condemned to death, is offered a lifeline by a mysterious stranger. In return, she must set aside her bid for vengeance against the man who destroyed all that she once loved. Not only that: for seven years she must agree to help anyone who asks for her aid. She and her companion Grim settle on the fringes of a mysterious forest in Dalriada, far from the place of their incarceration, and start a new life.

Oran, the crown prince of Dalriada, is waiting for his bride-to-be, Lady Flidais. Her letters and sweet portrait have convinced him that she is his destined true love.

But letters can lie.

To save Oran from disaster, Blackthorn and Grim will need courage, ingenuity, and more than a little magic.

Contents

To the daughters of Papatuanuku

CHARACTER LIST

Approximate pronunciations are given for the more difficult names.

kh = soft guttural, as in Scottish ‘loch’

LAOIS / LAIGIN (Leesh / Lain) | ||

Blackthorn | a prisoner | |

Grim | a prisoner | |

Poxy | prisoners | |

Dribbles | ||

Strangler | ||

Frog Spawn | ||

Slammer | a prison guard | |

Tiny | a prison guard | |

Mathuin | chieftain of Laois in northern Laigin | |

Conmael | a fey nobleman | |

ULAID | ||

Muadan | chieftain of southern Ulaid | |

Breda | Muadan’s wife | |

DALRIADA | ||

Oran | Prince of Dalriada | |

Ruairi | ( | Oran’s father, King of Dalriada. His court is at Cahercorcan |

Eabha | ( | Oran’s mother, Queen of Dalriada |

Lady Sochla | ( | Eabha’s sister, Oran’s aunt |

Sinead | (shi- | her personal maid |

Feabhal | (fa-val) | Ruairi’s chief councillor |

Master Cael | a senior lawman | |

Master Tassach | a senior lawman | |

Oisin | (a-sheen) | a druid |

Oran’s household at Winterfalls | ||

Donagan | Oran’s body servant and friend | |

Aedan | steward | |

Fíona | his wife | |

Eochu | ( | stable master |

Niall | head farmer | |

Brid | head cook | |

Teafa | ( | a young seamstress |

Lochlan | head guard | |

Garalt | guard | |

Fergal | guard | |

Winterfalls village | ||

Fraoch | (frech) | smith |

Ornait | his mother | |

Emer | ( | his younger sister |

Iobhar | (ee-var) | brewer |

Eibhlin | ( | his wife |

Scannal | miller | |

Deaman | (da-maun) | baker |

Luach | (lokh) | weaver |

Becca | a friend of Emer | |

Cathan | Becca’s first love | |

Brocc | sheep farmer | |

Cliona | sheep farmer | |

Pátraic | lad from the brewery | |

Silverlake village | ||

Branoc | baker | |

Ernan | miller (deceased) | |

Ness | Ernan’s daughter | |

Mór | a villager | |

CLOUD HILL / LAIGIN | ||

Lord Cadhan | chieftain of Cloud Hill in northern Laigin | |

Flidais | ( | his daughter |

Domnall | ( | senior man-at-arms, married to Nuala |

Eoin | (ohn) | man-at-arms |

Seanan | ( | man-at-arms |

Ciar | (keer) | Flidais’s personal maid |

Mhairi | ( | maidservant |

Deirdre | ( | maidservant |

Nuala | ( | maidservant, married to Domnall |

OTHERS | ||

Lorcan mac Cellaig | King of Mide (an historical figure, circa 848) | |

Abhan | (a-van) | a travelling horse trader |

and not forgetting | ||

Snow | Oran’s horse | |

Star | Donagan’s horse | |

Apple | Flidais’s horse | |

Storm and Sturdy | Scannal’s cart horses | |

Tinker and Treasure | Abhan’s cart horses | |

Bramble | Flidais’s dog |

1

~BLACKTHORN~

I

fished out the rusty nail from under my pallet and scratched another mark on the wall. Tomorrow would be midsummer, not that a person could tell rain from shine in this cesspit. I’d been here a year. A whole year of filth and abuse and being shoved back down the moment I lifted myself so much as an inch. Tomorrow, at last, I’d get my chance to speak out. Tomorrow I would tell my story.

In the darkness of the cell opposite, Grim began muttering. A moment later the door down at the guard post creaked open. How Grim could tell the guards were coming before we heard them was a mystery, but he always knew. The muttering was a kind of shield. At night, when the place belonged to us prisoners, he spoke more sense.

A jingle of metal; footsteps approaching. Long strides, heavy footed. Slammer. Usually, when he came, we’d shrink back into the shadows, hoping not to draw his attention. Today I stood by the bars waiting. My time in this place had broken me down. The person they’d locked up last summer was gone, and she wasn’t coming back. But tomorrow I’d speak for that woman, the one I had been. Tomorrow I’d tell the truth, and if the council had any sense of right and wrong, they’d make sure justice was done. The thought of that kept me on my feet even when Slammer went into his little routine, smashing his club into the bars of each cell in turn, liking the way it made us jump. Yelling his stupid names for us, names that had stuck like manure on a boot, so we even used them for one another, Grim and I being the only exceptions. Peering in to make sure we looked sufficiently cowed and beaten down.

‘Bonehead!’ The club crashed against Grim’s bars. ‘Stop your stupid drivelling!’

At the back of his cell Grim was a dark bundle against the wall, head down on drawn-up knees, hands over ears, still muttering away. Funny thing was, if Slammer had opened that cell door just a crack, Grim could have killed him with his bare hands and not raised a sweat doing it. I’d seen him at night, pulling himself up on the bars, standing on his hands, keeping himself strong as if there might be giants to kill in the morning.

The guard turned my way. ‘Slut!’

Crash!

I wished I had the strength to keep quite still as the club thumped the bars right by my head, but the three hundred and fifty-odd days had taken their toll, and I couldn’t help wincing. Slammer didn’t move on to the cell next door as usual. He stopped on the other side of the bars, squinting through at me. Pig.

‘Got something to tell you, Slut.’ His voice was a confidential murmur now; it made my skin crawl.

Slammer liked playing games. He was always teasing the men with talk of messages from home, or hinting at opportunities for getting out. He was a liar. They all were.

‘Something you won’t like,’ he said.

‘If I won’t like it, why would I want to hear it?’

‘Oh, you’ll want to hear this.’ He put his face right next to the bars, so close I could smell his foul breath. Not that it made much difference; the whole place stank of unwashed bodies and overflowing latrine buckets and plain despair. ‘It’s about tomorrow.’

‘If you’re here to tell me that tomorrow’s the midsummer council, don’t trouble yourself. I’ve been waiting for this since the day I was thrown into this festering dump.’

‘Ah,’ said Slammer in a voice I liked even less than the previous one. ‘That’s just it.’

Meaning, I could tell, exactly the opposite. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘Now you’re interested.’

‘What do you mean,

that’s just it

?’

‘What’ll you give me, if I tell you?’

‘This,’ I said, and spat in his face. He was asking for it.

‘Euch!’ He wiped a sleeve across his cheek. ‘Filthy whore!’

Filthy was right; but not the other. I’d never given myself willingly in here, and I’d never been paid for the privilege. The guards had taken what they wanted in those first days, when I’d still been fresh; when I’d looked and felt and smelled like a woman. They didn’t bother me now. None of them was desperate enough to want the rank, skinny, lice-ridden creature I’d become. Which meant I had nothing at all to offer Slammer in return for whatever scrap of information he was teasing me with.

‘That’s the last time you’ll spit at me, Slut!’ hissed Slammer.

‘You’re right for once, since I’ll be out of this place tomorrow.’

He smiled, but his eyes stayed cold. ‘Uh-huh.’ The way he said it meant I was wrong. But I wasn’t. I’d been told my name was on the list. The law said a chieftain couldn’t keep prisoners in custody more than a year without hearing their cases. And with all the chieftains of Laigin here, even a wretch like Mathuin, who didn’t deserve the title of chieftain, would abide by the rules.

‘You’ll be out, all right,’ Slammer said. ‘But not the way you think.’

Oh, he was enjoying this, whatever it was. My mouth went dry. Over in the cell opposite, Grim had fallen silent. I couldn’t see him now; Slammer’s bulk took up all my space. I forced myself to keep quiet. I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of hearing me beg.

‘You must have really got up Mathuin’s nose,’ he said. ‘What did you do to make him so angry?’ Perhaps knowing he wouldn’t get an answer, Slammer went right on. ‘Overheard a little exchange. Someone wants you out of the way

before

the hearing, not after.’

‘Out of the way?’

‘Someone wants to make sure your case never goes before the council. First thing in the morning, you’re to be disposed of. Quick, quiet, final. Name crossed off the list. No need to bother the chieftains with any of it.’ He was scrutinising me between the bars, waiting for me to weep, collapse, scream defiance.

‘Why have you told me this?’ A lie. A trick. He was full of them. I willed my heart to slow down, but it was hopping all over the place like a creature in a trap.

‘What, you’d sooner not know until I drag you out there in the morning and someone gives you a nasty surprise? Little knife in the heart, pair of thumbs to the throat?’

‘You’re lying.’

‘Better say your prayers, Slut.’ He moved off along the row. ‘Poxy!’

Smash!

‘Strangler!’

Crash!

‘Frog Spawn!’

Slam!

Across the walkway, Grim was standing at the front of his cell, big hands wrapped around the bars.

‘What are you looking at?’ I snarled, turning away before my face could show him anything. The three hundred and fifty-odd marks stared back from the wall, mocking me. Not a count to freedom and justice after all; only a count to a swift and violent end. Because, deep down, I knew this must be true. Slammer didn’t have the imagination to play a trick like this.

‘Lady?’

‘Shut your mouth, Grim! I never want to hear your wretched voice again!’ I sank down on the straw pallet with its teeming population of insects. Even these fleas would live longer than me. I wished I could find that amusing. Instead, the anger built and built, as if the swarm of crawling things was inside me, breeding and multiplying and spreading out into every corner of my body until I was ready to burst. How could this be? I’d held out here for one reason and one reason only. I’d endured all those poxy days and wretched, vermin-infested nights, I’d listened to that idiot Grim mumbling away, I’d seen and heard enough to give me a lifetime of nightmares. And I’d stayed alive. I’d held on to one thing: the knowledge that eventually I’d get my day to be heard. Midsummer. The council. It was the law. Curse it! I’d done it all for this day, this one day! They couldn’t take it away!

The crawling things broke out all at once. From a distance, detached, I watched myself hurling objects around the cell, heard myself shouting invective, felt myself hitting my head on the wall, slamming my shoulder into the bars, ripping at my hair, my mouth stretched in a big ugly square of hatred. Felt the tears and snot and blood dribbling down my face, felt the filth and shame and utter pointlessness of it all, knew, finally, what it was that drove so many in here to cut and maim and, eventually, make an end of themselves. ‘Slammer, you liar!’ I screamed. ‘You’re full of shit! It’s not true, it can’t be! Come back here and say it again, go on, I dare you! Filthy vermin! Rancid scum!’

It was catching, this kind of thing. Pretty soon everyone in the cells was shouting along with me, half of them yelling at Slammer and the other guards and the unfairness of everything, the rest abusing me for disturbing them, though there wasn’t much to disturb in here. Crashes and thumps told me I wasn’t the only one throwing things.

All the while, there was Grim, standing up against his own bars, silent and still, watching me.

‘What are you staring at, dimwit?’ I wiped a sleeve across my face. ‘Didn’t you hear me? Mind your own business!’

He retreated to the back of his cell, not because of anything I had said, but because down the end of the walkway the door had crashed open again and the guards were coming through at a run. It was the usual when we got noisy: buckets of cold water hurled in to drench us. If that didn’t work, someone would be dragged out and made an example of, and this time around that person would have to be me. Not that a beating made any difference. Not if Slammer had been telling the truth.

I got a bucket of slops. There was a bit of cursing from the others, but everyone stopped yelling, not wanting worse. The guards left, taking their empty buckets with them, and there I was, dripping, stinking, bruised and bleeding from my own efforts, with the buzzing insects of my fury still swarming inside me. The cell was a mess, and with wretched Grim over there, only a few paces away, there was nowhere to hide. Nowhere I could curl up in a ball with the blankets over my head and cry. Nowhere I could give way to the terror of knowing that in the morning I would die, and Mathuin would be alive and going about his daily business, free to do to other folk’s families what he had done to mine. I would die with my loved ones unavenged.

I scrabbled on the floor, searching among the things I’d hurled everywhere, and my fingers closed around the rusty nail. Those marks on the wall were mocking me; they were making a liar of me. I hated the story they told. I loathed the failure they showed me to be. Weak. Pathetic. A vow-breaker. A loser. With the nail clutched in my fist I scratched between them, around them, over them, making the orderly groups of five, four vertical, one linking horizontal, into a chaotic mess of scribble. What was the point in hope, when someone always snatched it away? Why bother telling the truth if nobody would listen? What use was going on when nobody cared if you lived or died?

I waited for death. Thought how odd human nature was. All paths were barred, all doors closed. There was no escaping what was coming. And yet, when the guard known as Tiny – a very tall man – brought around the lumpy grey swill that passed for food in this place, I took my bowl and ate. We were always hungry. One or two of the men caught rats sometimes and chewed them raw. I’d never had the stomach for that, though Strangler, in the cell next to mine, always offered me a share. In the early days we used to talk about food a lot; imagine the first meal we’d have when they let us out. Fresh fish cooked over a campfire. Mutton-fat porridge. Roast duck with walnut stuffing. Carrot and parsnip mashed with butter. For me it was a chunk of bread and cheese or a crisp new apple. When I thought of that first bite my belly ached and so did my heart. Then I’d got beaten down and worn out, like an old mattress with the stuffing gone to nothing, and I didn’t care anymore. Same with the others; we were grateful for the swill, and thankful that Tiny didn’t rattle our cages and scream at us. So, even when I was looking death in the eye, so to speak, I ate. Across the walkway, Grim was on his pallet, scooping up his own share and trying to watch me and avoid my eye at the same time.

The long day passed as they always did. Grim muttered to himself on and off, making no sense at all. Frog Spawn went through his list of all those who had offended him, and what he planned to do to them when he got out. It was a long list and we all knew it intimately, since he recited it every day. The others were quiet, though Poxy did ask me at one point if I was all right, and I snarled, ‘What do you think?’, making it clear I didn’t want an answer.

I sat on the floor, trying out the pose Grim seemed to find most comforting when under threat, head on knees, arms around legs, eyes squeezed shut. The day before you died was the longest, slowest day ever. It gave you more time than you could possibly want to contemplate all the things you’d got wrong, the chances you’d missed, the errors you’d made. It was long enough to convince the most hopeful person that there was no point in anything. If only this . . . if only that . . . if only I had my chance, my one chance to be heard . . .

Another round of swill told us it was getting on for night time; a person wouldn’t know from the windows, which were kept shuttered. It was a long time since they’d last let us out into the courtyard. Maybe Mathuin’s men didn’t know folk could die from lack of sunshine. Our only light came from a lantern down the end of the walkway.

Frog Spawn’s ravings slowed then stopped as he fell asleep.

‘Hey, Slut!’ called Strangler. ‘Place won’t be the same without you!’

‘Our lovely lady,’ put in Poxy, mostly mocking, a little bit serious. ‘We’ll miss you.’

‘Don’t let the vermin take you without a fight, Slut,’ came the voice of Dribbles from down the far end. ‘Give ’em your best, tooth and nail.’

‘When I want your advice,’ I said, ‘I’ll ask for it.’

‘Wake us up when they come for you,’ said Strangler. ‘We’ll give you a proper send-off. Worth a bucket or two of slops.’

Grim wasn’t saying anything, just sitting there gazing across at me, a big lump of a man with a filthy mane of hair, a bristling beard and sad eyes.

‘Stop looking at me,’ I muttered, wondering how I was going to get through the night without going as crazy as Frog Spawn. If there was nothing I could do about this, why was my mind teeming with all the bad memories, all the wrongs I hadn’t managed to put right? Why was the hate, the bitterness, the will for vengeance still burning in me, deep down, when the last hope was gone?