Dresden (2 page)

Authors: Frederick Taylor

Saxons

SILVER GRAY

CLOUDS blurring into slate gray sea on the misty horizon. Villages crouched between marshlands and shifting sands, hostage to the pitiless easterly winds and to the restless, fierce invaders from the northwestern part of Germany, known as Saxonia. It was their ships that those cold winds brought lurching across the North Sea and scudding onto its sandy beaches.

More than a millennium and a half ago, when the Romans still ruled the island of Britain, they called its vulnerable, low-lying eastern coast the Saxon Shore, and appointed a count to the onerous task of organizing its defenses. This was around A. D. 350.

In the end, the wooden forts and the ditches and the local forces were too few, and the invaders from the sea too many. Even before the Romans left, the Saxons had gained a foothold. Within a century they had expelled or absorbed the Celto-Roman natives and given their own flat names to the great, flat counties of Eastern England. Norfolk. Suffolk. The kingdom of Lindsey, later to be known as Lincolnshire. The transplanted Saxons, along with the other German tribes who had also settled in the former Roman province, with a mixing-in of Dane and Norman from later continental incursions, became the peoples known all over the world as the English, or the Anglo-Saxons.

As for those continental Saxons, the ones who had not sailed west to Britain all those centuries ago, they instead moved farther into the heart of Europe. They infiltrated the Slav lands, expelling or absorbing the original natives, just as their relatives had done in Britain. These East Saxons too finally converted to Christianity, founded towns, fought wars, traded and farmed and worked minerals, produced great art, and hoarded great riches. Partly against their will,

they became part of a united Germany toward the end of the nineteenth century.

By the fifth decade of the twentieth century, the English have vast wealth, an empire spread throughout the globe, great cities, a navy, army, and air force. Latterly the air force has become a new symbol of the nation's power. Much of it is based in Lincolnshire and Norfolk and Suffolk, the subdivisions of the Saxon Shore. “Bomber country,” as it has been dubbed. Where fifteen hundred years ago these flat, exposed counties presented a reception platform, open for invaders to swarm ashore, by the 1940s they are crisscrossed with hastily built concrete runways. They are now the launch decks of an island aircraft carrier facing east toward the continent.

It is the year 1945. The Anglo-Saxons are engaged in war to the death with their distant family across the North Sea, from whom they had divided so long ago and far away. As a consequence, aircraft laden with bombs are taking off from the wintry fields of Lincolnshire on a belated reverse voyage this February afternoon.

The fliers' mission is to wreak a terrible revenge on those German relatives' most proud and beautiful treasures, as well as on the most precious thing they haveâtheir lives.

Â

TWILIGHT. FEBRUARY 13, 1945,

Shrove Tuesday. The first waves of aircraft are taking off. The ponderous flocks further darkening the winter sky are made up of Avro Lancaster heavy bombers, attached to 5 Group of Bomber Command. They are bound for a rendezvous point over Berkshire. Their armorâperfunctory to start withâhas been further depleted to save weight, and the planes have been equipped with extra fuel tanks because of the exceptional seventeen-hundred-mile round-trip distance to the target. Each Lancaster, big with a seven-ton load of bombs and incendiary devices, wields twice the destructive capacity of the famous American Flying Fortresses and Liberators. By 6

P.M

., in the gathering darkness, a total of 244 bombers are circling together in the air, the town of Reading blacked out thousands of feet beneath them, ready to set course.

The aircrew have been routinely briefed that afternoon, and their target described as follows:

The seventh largest city in Germany and not much smaller than Manchester, is also by far the largest unbombed built-up area the enemy has got. In the midst of winter with refugees pouring westwards and troops to be rested, roofs are at a premium, not only to give shelter to workers, refugees and troops alike, but also to house the administrative services evacuated from other areasâ¦

The target sounds workaday, scarcely worthy of special notice in the busy schedule of the massive, sophisticated machine of destruction that Bomber Command has become. This is deceptive, and perhaps the briefing's tone is deliberately disingenuous. This particular city has been renowned over centuries for its architectural beauty and

douceur de vivre

, and in that respect the war has until now changed surprisingly little. Its name is Dresden.

Although the spearheads of the Russian armies have temporarily halted about seventy miles to the east, and a stream of refugees from the eastern front has recently begun to tax the city's housing resources, the situation remains surprisingly calm. The theaters and opera houseâwhere works by Webern and Wagner and Richard Strauss saw their first performancesâare temporarily closed under orders from Berlin, but Dresden's famous cafés are still open for business. Tonight the Circus Sarrasani is staging a show at its famous domed “tent” just north of the river, drawing hordes of sensation-eager spectators.

How can Dresden know that for some time it has been marked out for destruction? Weeks of bad weather, making accurate bombing difficult if not impossible, have saved its people until now. Today over the target city, conditions have cleared. Unlike other parts of Germany farther to the west, the area has experienced a pleasant day leading into a cold, dry night with only light cloud. What the Germans call

Vorfrühling

. Pre-spring. This simple, cruel meteorological fact has finally sealed the city's fate.

The Lancasters have reached their cruising speed of around 220 miles per hour, flying in layers at between seventeen thousand and nineteen thousand feet to avoid collisions. They maintain a southeasterly course at first, breasting the French coast over the Pas de Calais, continuing over northern France until they reach a point roughly

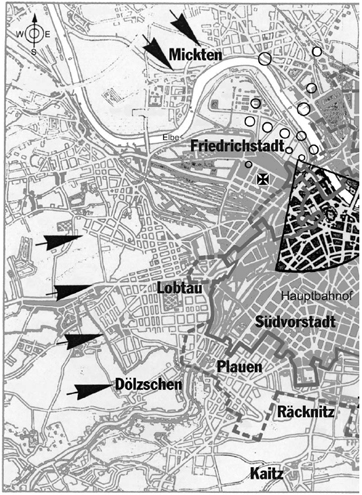

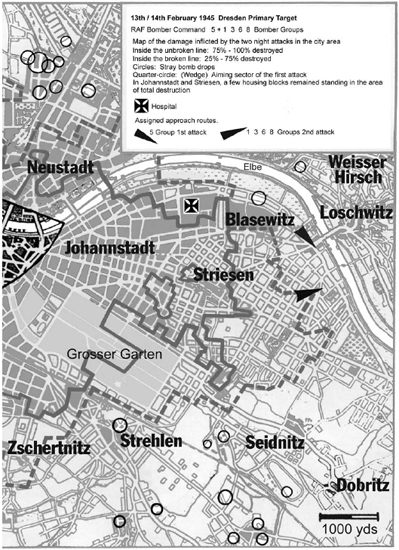

halfway between Reims and Liège. There the formation banks northeast, heading for the border city of Aachenânow in Allied handsâbefore setting course due east, over the front line into enemy-held territory. Soon the bombers pass, as planned, just to the south of the Ruhr industrial area, avoiding its massive concentrations of well-practiced antiaircraft batteries. Here is where they also pass beyond the protective shield of “Mandrel,” the jamming screen provided by the RAF's 100 Group to fog the enemy radar defenses. “Window” devices are dropped in the thousands to further confuse the enemy. En masse, these small strips of metal appear on German radar screens as a wandering bomber fleet while the real aircraft do their work elsewhere. These measures will be especially effective tonight, for the area west of the target remains blanketed with thick cloud, making visual tracking of aircraft movements impossible.

At 9:51

P.M

. in Dresden the air raid sirens sound, as they have so often during the past five years, and until now almost always a false alarm. The city's people, and especially its children, have spent the day celebrating a somewhat toned-down, wartime version of Fasching, the German carnival. Many of them, and again especially the children, are still in their party costumes. There are, perhaps, even more than the usual laughter, the usual jokes, as families sigh and head for their cellars. Stragglers, hearing the alarm, scuttle home through the winding, cobbled streets of the old town, or pick up their pace as they make their way past the grand buildings of the Residenz.

There are remarkably few major public air raid shelters for a city of this size. One of the largest, beneath the main railway station, built for two thousand people, is currently housing six thousand refugees from the eastern front. The Gauleiterâthe local Nazi Party leader but also the province's governor and defense commissionerâhas consistently failed to divert the necessary resources to remedy this situation, although (as his subjects are well aware) he has commandeered SS engineers to build sturdy shelters beneath both his office and in the garden of his personal residence. In the latter case he has put a reinforced concrete shield several meters deep between himself and the bombs he has always insisted will never fall.

Meanwhile, after four hours in the air, the bombers are reaching the end of their outward flight. The Luftwaffe has not contested the airspace (the only enemy aircraft shot down that night will be an

unlucky German courier plane which crosses the path of the British air armada en route between Leipzig and Berlin). The visibility remains poor, even as the Lancasters begin their final approach to the target. Only now, as they track the southeastward curve of the river Elbe, does the cloud cover begin to disperse. The bomber aircrew, whenever there are gaps in the cloud, can look down and glimpse landmarks, roads and railways, occasional lights three miles or more below them. They wait, watch for enemy night fighters, and fly on over darkened woods and fields, over the icy ribbons of the country roads that link the neat, slumbering villages of Middle Germany.

So farâand the aircrew know to be thankful for thisâit is an altogether uneventful trip. Even now, few in the target city have any inkling of what is to follow. There had, after all, been no “prealarm.” In the industrial center of Leipzig, fifty miles to the west and already subjected to heavy bombing earlier in the war, specific warnings have already been issued over the radio. But in the target city the authorities have chosen not to place their fellow citizens on any kind of special alert. At this point the controllers at the Luftwaffe's tracking stations know that one of the major eastern population centers is being targeted. However, they share Germany's and much of the world's conviction that Dresden will never be subjected to serious bombing.

One of the myths, then and now, is that this city has been completely spared until tonight. Over the previous few months there had been a scattering of daylight raids by American formations on the suburban industrial areas and on the marshaling yards just outside the city center. Adjacent residential blocks had actually been hit a month previously, at the cost of more than three hundred civilian fatalities. But most citizens put these incidents down to mischance or poor navigation, and still consider the city inviolable. There are many rumors about why Dresden has not been, and will not be, subjected to the massive destruction meted out to other towns in the Reich.

Ten minutes after the first air raid alarm, an advance guard of fast, light RAF De Havilland Mosquito Pathfinders from 627 Squadron swoop unchallenged over the darkened buildings. Their job is to identify and mark the target. They begin to drop the marker flaresâknown to German civilians as “Christmas trees.” These will enable the huge force of following bombers to find their targets. Their focus is the stadium of the city's soccer club, just to the west of the old city. It

is suddenly clear from this that the bombers are aiming not just for the city's industrial suburbs and adjacent marshaling yards but its treasured historic heart. Only when they hear the Mosquito's engines overhead do the local civil defense authorities, on alert in their bunker beneath police headquarters, realize that their city is actually going to be bombed. The frantic voice of an announcer comes on the local cable radio, telling citizens to get off the streets on pain of arrestâto take the best cover they can.

There are no antiaircraft guns to be readied. No searchlights probe the skies. Just a few weeks before, the sparse flak defenses of the cityâmuch of it light guns and captured Soviet pieces not thought highly of by their crewsâwere dismantled and shipped away, some westward to the heavily bombed Ruhr industrial districts and others to the hard-pressed eastern front. The city is completely unprotected.

One man's diary for February 13 also describes “perfect spring weather” in Dresden during the daylight hours. But there is nothing else cheerful about his report of the day's events. This citizen, Professor Victor Klemperer, changed careers in early middle age from journalist and critic to become a distinguished academic. A decorated veteran of World War I and a firm German patriot, in the past ten years he has lost his job, his house, and his savings. He is not permitted to own or drive a car or a bicycle, or to use public transport. He cannot keep pets. There are certain streets he cannot walk along, or can cross only via specific junctions. This is because Klemperer is Jewish. He has been saved from “deportation” until now, not because his family has been established in Germany for two hundred years, but because he is married to an “Aryan.”

*

And today, he reports in the pages of his journal, he has been touring the homes of the few other Jews still remaining in the city (about two hundred out of a prewar total of six thousand), to tell them that they will be deported to an undisclosed “labor task” in three days' time, on February 16. Every one of them knows what this means.

That evening, arriving back at the house he and his wife share

with other Jewish survivors since their own home was confiscated, he eats a modest dinner. Klemperer sits down to coffee just as the air raid sirens sound. Then they hear aircraft overhead. One of his companions says with bitter prescience: “If only they would smash everything.”

The Lancasters are over their target; their bomb doors have opened. The raid is under way. The first wave of destruction lasts between fifteen and twenty minutes. The second, two hours later and featuring even more aircraft, lasts slightly longer. The time lag is a deliberate, cold-blooded ploy on the part of Bomber Command's planners, who have become expert at such pieces of business. By this time many who survived the first raid will be back above ground, and there will be firefighters, medical teams, and military units on the streetsâincluding auxiliaries who have raced along frozen roads from as far away as Berlin. Now a fresh hail of high explosive and incendiary bombs will suck the individual existing fires into one, and the firestorm will begin to build. In the morning Flying Fortresses of the Eighth U. S. Army Air Force will finish the work of destruction. Dresden is doomed.