Dublin Folktales (16 page)

Authors: Brendan Nolan

On the following morning, the people of Dún Laoghaire awoke to find their harbour filled with debris and wreckage from boats that foundered in the storm and were now thrown ashore in bits and pieces. Dozens of bodies of drowned mariners and others were taken from the water and laid out in sorrowful lines on dry land. At sea, the waves still rolled on in the aftermath of the storm, while falling snow, sleet and rain reduced visibility and chilled the hands, feet and faces of the rescuers.

Among the wailing, searching, grappling and dragging of the wreckage, the crew of the Royal Naval coastguard ship,

Ajax

, under Captain John McNeill Boyd went about their duties. The Royal Navy maintained a constant presence in Dún Laoghaire, then called Kingstown, all year round. HMS

Ajax

was on station from 1858 until 1864. Built in 1809 as a seventy-four gun wooden ship of the line; she was described as being like many that fought at Trafalgar under Nelson. The

Ajax

was fitted with an auxiliary steam engine in 1846. However, she was noted for her poor performance under both sail and steam. Paradoxically, Boyd and his men were to be drowned from dry land while attempting a marine rescue of fellow sailors.

On the fateful day, when even more men joined the drowned of the night before, it was reported that three

stricken vessels the

Neptune

, the

Industry

and the

Mary

, carrying cargoes of coal from Britain, were making for the safety of the harbour. Fierce winds conspired to sweep them towards the treacherous rocks off the East Pier. They could not make safety, no matter what their level of maritime skill or what they did to correct their course. Boyd and his sailors, along with officers and men of the Kingstown district coastguard, hurried towards the rocks to attempt to save some of the unfortunate men from the ships when they struck. It being still winter time with temperatures well down below comfort, many of the rescuers were dressed in heavy clothing. Witnesses said Boyd himself was encumbered by his greatcoat, and started to take it off so as to move easier in the tough conditions. But as he did so, a large wave, as high as a mountain, crashed over him and his men, and they disappeared into the churning waters along with everyone else that had been standing there.

In the event, two of the vessels, the

Neptune

and the

Industry

, from Whitehaven, were wrecked within 100 yards of each other with great loss of life. The third ship, the

Mary

, was swept on to Sandymount a distance away to the north of the others where it was also wrecked. The bodies of Boyd and his men were not recovered from the sea for some days, despite extensive searches by boats and the crew of the

Ajax

and other searchers. Lost with Boyd were: Able Seamen John Curry and Thomas Murray; Ordinary Seamen John Russell, James Johnson and Alexander Forsythe.

When some calm returned and a lifeboat from the

Ajax

patrolled the waters, observers saw the captain’s black dog sat in the prow, desperately seeking its companion and master. The bodies of the crewmen were washed ashore days later, but the sea was not to give up the body of the courageous Boyd for weeks.

The remains of the crew members of the

Ajax

were buried in the graveyard at Carrickbrennan in Monkstown, near Dún Laoghaire. While his companions were buried near to

the events of the day, Boyd’s remains were interred in the grounds of St Patrick’s Cathedral, in Dublin city, where a memorial was erected within the Cathedral to him. His body was brought to the cathedral in funeral procession. It was reportedly one of the biggest funerals seen in Dublin, with thousands of people walking in the cortege.

Many noticed that the captain’s dog walked behind the hearse. It stayed close to Boyd as his body lay in state in the Cathedral. The dog sat as if waiting its master’s call to sail the seas once more, a call that was not to come. When the remains were brought to the graveyard to be buried, the dog followed it to the graveside. Even when the solemn ceremonies had ended, and the grave was filled in, the dog remained with its master. It lay on top of the grave and refused to leave, eventually expiring of hunger, despite attempts to entice it away or to get it to eat. Another life ended, in an ongoing tragedy.

Then, a strange thing happened that few could explain, but that is still spoken of to this day in Dublin. A memorial statue was erected in St Patrick’s Cathedral by the citizens of Dublin to the memory of Captain Boyd. The inscription on the statue reads, ‘Erected by the citizens of Dublin, to the memory of John McNeill Boyd, R.N., Captain, H.M.S. Ajax, born Londonderry, 1812, and lost off the rocks at Kingstown, February 9th, 1861, attempting to save the crew of the Brig, Neptune.’ In the time that followed, the shadowy figure of a dog was seen at night, sitting at the base of the statue, and at other times by the grave of the drowned sailor. The last person on record said to have seen the ghost dog died in 1950.

Boyd was posthumously awarded the Sea Gallantry Medal in silver, the RNLI silver medal and the Tayleur Fund medal in gold for his rescue actions that day. The RNLI citation read how Captain Boyd then serving in the screw steamer HMS

Ajax

, assisted in saving the crew of the brig

Neptune

wrecked during a heavy gale on the East Pier

of Kingstown, County Dublin. The silver medal, accompanied by a letter of condolence, was presented to his widow Cordelia. His inscription in St Patrick’s Cathedral reads:

Safe from the rocks,

Whence swept thy manly form

The tide white rush,

The stepping of the storm.

Borne with a public pomp,

By just decree

Heroic sailor!

From that fatal sea.

A city vows this marble unto thee,

And here in this calm place, where never sin

of earth great waterfloods shall enter in.

When to our human hearts, two thoughts are given,

One, Christ’s self-sacrifice, the other heaven.

Here is it meet for grief and love to grave

The Christ-taught bravery that died to save

The life not lost but found beneath the wave.

All Thy billows and Thy Waves passed over me, yet

I will look again toward Thy Holy Temple.

There is no memorial to his faithful dog who was steadfast both in life and in death. But he stayed true, public memorial or no.

L

ITTLE

J

OHN IN

D

UBLIN

Even outlaws like to go on holiday.

It seems that John Little or Little John of Sherwood Forest, who was reputedly one of the most famous outlaws in England in his day, came to Dublin to visit some of the local vagabonds and to inspect the caves around Arbour Hill, situated near the present day Phoenix Park. He did so when his glory days as an outlaw in England had ended.

But unlike most visitors to the city, he was never to leave Dublin again. Instead, he was hanged for his misdeeds in Dublin some time in the twelfth century, according to local legend.

Gilbert’s

History of the City of Dublin

suggested that Little John, second in command to the romantic outlaw Robin Hood, travelled to Dublin and Oxmantown when Robin and his band of merry men were finally disbanded. It’s a plausible enough story, given that there had long been trade between England and Ireland by sea. Little John, and anyone else that cared to travel with him, could easily have travelled to Dublin on a trading ship.

Once arrived, he would have found the terrain to the north of the river not unfamiliar to his eye. While there would not have been the vast forests of oak trees he was accustomed to hanging out in, many caves dotted the terrain. The great oak forest that used to stand at Arbour

Hill had been cut down and shipped to London, where at least some of it found its way into the roof timbers of Westminster Abbey. But great roots still lay beneath the soil.

Beneath the land at Arbour Hill lay a labyrinth of caverns, much used by thieves and others to escape into and to conceal their stolen goods from pursuers. Back in Little John’s hunting ground at Nottingham, the castle sat on an easily-defended cliff above a network of sandstone caves below. Indeed, there were many caves, hills, and wooded areas of concealment in and around the area of Sherwood Forest which in Little John’s time stretched for a distance of some twenty miles.

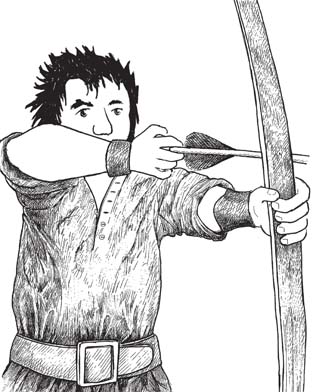

A story lingers on in Dublin that the visiting outlaw fired an arrow from his long bow, a distance of some 700 metres, from the only bridge the crossed the Liffey at the time upwards towards Arbour Hill. Whether this was to show his accuracy with the weapon of choice of the Merry Men back home or simply to re-enforce his mystique as a mighty man is lost in time. It might even have been as part of a wager. Certainly, the locals would have encouraged any stranger to show his mettle, for a Dubliner likes to take the measure of a visitor.

It is interesting how the Dublin story features Little John standing on a bridge to draw his longbow, when stories of his first encounter with Robin Hood involve Little John trying to prevent Robin from crossing a narrow bridge. The two are said to have fought one another with hardwood quarter staves, with Robin being knocked into the river by his opponent when he lost the stick fight. Despite being the victor of the battle, John Little is said to have agreed to join Robin’s band and to be subservient to him. That he was reputedly a giant of a man standing some seven feet in height when most Dubliners would have been teetering around the five-foot mark, would have made him stand out even more. But, who knows how tall he was, for height is often a matter of subjective comment. If someone defeated

a warrior from another country, he would of course have been a worthy opponent and taller in the telling. Conversely, if the head was still ringing from the pummelling received, the loser would doubtless swear it was a giant of man that beat him despite his best and heroic efforts to fight his corner.

The old bridge from which the big man shot his arrow spanned the river where the present bridge now crosses from Church Street to Bridge Street, near the Four Courts. The main road through Dublin, from Tara in County Meath to the north to Wicklow and the southern counties, crossed the Liffey at this point. If Little John had lived a few centuries later, he could have shown his expertise in shooting deer in the new royal deer park at Phoenix Park beside the cave area, but that was not to be formed until the seventeenth century, when his visit had already faded into local lore.

The county gallows was moved away from modern Parkgate Street to Kilmainham, south of the river, to make way for a grand entrance to the park in the 1600s. Thieves and others were still hanged in public gaze. However, even after the removal of the gallows, the end result was much the same if it was your day for the hangman to greet you with a rope necklace.

If he was in the city as a type of consultant, then perhaps Little John joined local brigands in robbing and relieving travellers and merchants of their goods as they passed along towards the single Liffey bridge. Perhaps the English outlaw in Dublin might even have been an impostor living on the

legend of Little John. Whatever the truth of the story, someone was caught and duly hanged for his troubles.

This man, impostor or not, was hanged at Gibbet’s Glade, a place of public execution for criminals. We do not know what happened to his body afterwards. Being hanged from a gibbet as a punishment usually meant the dead body was left to hang in the air for as long as the authorities saw fit, as warning to all. Sometimes, they swung there until their clothes rotted away; sometimes it was until the body decomposed. People said it made a mournful sound, when a dead man swung in the wind, waiting for his body to rot while crows pecked away at what was left. It made little difference to the deceased for he was past caring what was done to his person.

Otherwise, it was the custom of the hangman to toss the dead bodies of his charges into a nearby pit prepared for the purpose. So perhaps Little John joined other not-so-merry corpses in a hole in the ground somewhere on the northside of Dublin.

Except …

Little John’s fame and last resting place is claimed by the town of Hathersage in Derbyshire, England. It is also claimed that he was born there. A memorial tells us that Little John died in a cottage to the east of the churchyard. To complicate matters, the cottage is now said to have been destroyed at some time in the past. If Little John died in Derbyshire, then the Dublin impostor surely got a raw deal when he was hanged as someone else on the public gallows. Though it may have been rough justice, since the condemned man was undoubtedly a thief and lived in a time of savagery among thieves and the law itself, which hanged citizens for less reason than would be tolerated now.

Oxmantown and the area of Arbour Hill that Little John may have roamed through was for a long time treated as a separate part of Dublin, being, as it was, across the river from the seat of power and somewhat bordering the

countryside. It served as a market and trading area for people from outside the city who brought animals and goods to Dublin for sale and trade. With so many people coming and going and buying and selling goods, it was no wonder that thieves were attracted to this place to prey on those weaker than themselves and to rob them of the proceeds of their day’s trading.