Duke (62 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

Alice Babs, the principal vocal soloist, was a classically trained soprano from Sweden whom Ellington had first heard on a 1963 tour. He was so impressed by her singing that he recorded a small-group album with Babs, but it was the Second Sacred Concert that first brought her to the attention of American audiences. According to Ellington, “She sings opera, she sings lieder, she sings what we call jazz and blues, she sings like an instrument, she even yodels, and she can read any and all of it!” Not only did she have a silvery, extraordinarily wide-ranging voice, exact intonation, and near-flawless English diction, but she was also blessed with the unerring rhythmic sense of a natural-born jazz musician. The two solo sections that Ellington wrote for Babs bear out his description of her as “a composer’s dream . . . with [Babs] he can forget all the limitations and just write his heart out.” In “Heaven,” a high-flying vocal meditation with a Latin dance interlude, she manages not to be upstaged by Johnny Hodges at his most romantic. Even lovelier is “T.G.T.T.,” a wordless duet for soprano and electric piano whose asymmetrical melody, unusually for Ellington, appears to have been written on its own rather than emerging from its harmonies. As he explained in his program notes, the enigmatic title of the song “means

Too Good to Title,

because it violates conformity in the same way, we like to think, that Jesus Christ did. The phrases never end on the note you think they will. It is a piece even instrumentalists have trouble with, but Alice Babs read it at sight.”

Had Ellington worked with a musically experienced poet or librettist instead of writing his own text, the Second Sacred Concert would almost certainly have been taken up more widely. But he wanted, as with the First Sacred Concert and

My People

before it, to make a completely personal statement, and he had written the piece not for finicky aesthetes but true believers: “I think of myself as a messenger boy, one who tries to bring messages to people, not people who have never heard of God, but those who were more or less raised with the guidance of the Church.” So he wrote the lyrics himself, thereby saddling the Second Sacred Concert with his childlike, unreflective notions of spirituality, which ran to trite essays in speculative theology (“Heavenly Heaven to be / Is just the ultimate degree to be”) and the same wince-making hipsterisms that had marred its predecessor (“Freedom, Freedom must be won, / ’Cause Freedom’s even good fun”). Whitney Balliett questioned in

The New Yorker

whether Ellington was putting on his audience with some of the lyrics. He wasn’t, but it is regrettably true that one must listen

through

the text to hear the Second Sacred Concert for what it is, a flawed near-masterpiece in which some of his best music is allied to some of his worst lyrics.

• • •

The band’s shaky playing on the recording of the Second Sacred Concert, taped immediately after the premiere, provides further evidence of its growing decrepitude, which accelerated when Jimmy Hamilton and Sam Woodyard handed in their notices. Their replacements, Harold Ashby and Rufus Jones, were talented players, but the twin departures can be seen in retrospect as the beginning of the band’s final decline. While the loss of Ray Nance had been a shock, Cootie Williams’s presence helped soften the blow. From now on, by contrast, every departure would be irreparable.

For a time, though, things seemed to continue as before. Ellington toured Latin America for the first time in September, with the

Latin American Suite

following in due course. Yale had already presented him with an honorary degree, the first to be conferred by the university on a jazz musician, and now he was appointed to the National Council on the Arts.

†††††††††††

He even hired some interesting new players. One was the pioneering jazz organist Wild Bill Davis, who had arranged Count Basie’s hit version of “April in Paris” in 1955 and who now joined the Ellington band as a second keyboard player and sometime orchestrator. An individual stylist who had cut a number of small-group albums with Johnny Hodges, Davis might well have shifted the band’s musical direction, like Woodyard before him, had he come along a decade earlier. “Duke could have really incorporated him in the sound, written something

seriously

for him,” Norman Granz said. “But he didn’t. He just used Bill as a relief soloist most of the time.” Neither did he take advantage of Johnny Coles, a Miles Davis–influenced trumpeter who joined the band two years later. Coles had recorded to fine effect a decade earlier with Gil Evans, the greatest big-band arranger of the postwar era and one of the few whose command of orchestral color was comparable to that of Ellington and Strayhorn. But Ellington never got around to writing a feature for Coles, whose tenure became another missed opportunity.

The honors continued to pour in, and the grandest one of all took place on April 29, 1969, when President Nixon celebrated Ellington’s seventieth birthday by throwing a White House party at which he presented him with the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the American government. The idea for the party came from Joe Morgen, Ellington’s publicist. Willis Conover, the Voice of America disc jockey who had been beaming jazz behind the Iron Curtain since the fifties, planned the event, and Nixon himself decided to give the Medal of Freedom to Ellington. The party was universally recognized as a fitting and long-overdue tribute, not merely to Ellington but to jazz as a whole. As Ralph Ellison put it, “That which our institutions dedicated to the recognition of artistic achievement have been too prejudiced, negligent or concerned with European models and styles to do is finally being done by presidents.” If anything more were needed to erase the embarrassment of his having been denied a Pulitzer, this was it.

Conover assembled an all-star band to play for the black-tie affair. Invitations went out to a select list of politicians, musicians, and old friends and colleagues, among them Harold Arlen, Whitney Balliett, Dave Brubeck, Cab Calloway, Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Leonard Feather, Earl Hines, Mahalia Jackson, Marian McPartland, Otto Preminger, Richard Rodgers, Gunther Schuller, Willie “the Lion” Smith, and George Wein. Mercer and Ruth were there, too, along with a handful of Ellington alumni, including Fred Guy and Tom Whaley, who led the band, and Clark Terry and Louis Bellson, who played in it. But except for Harry Carney, who drove Ellington to the White House, none of the current members was present—they were on their way to Oklahoma City to play a concert—and neither, needless to say, were Evie or the Countess.

President Nixon addressed the crowd, describing the proceedings as “a very unusual and special evening.” He read the Medal of Freedom citation out loud: “In the royalty of American music, no man swings more or stands higher than the Duke.” Then he presented Ellington with the medal, and as everyone applauded, Ellington responded by administering to the president of the United States what Whitney Balliett, who was writing up the proceedings for

The New Yorker

’s “Talk of the Town” department, described as “the classic French greeting of left cheek against left cheek, right against right, left against left, and right against right.”

‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡

He thanked the president, saying, “There is no place I would rather be tonight except in my mother’s arms.” Nixon, an amateur pianist, played “Happy Birthday” in the key of G, after which the band went to work and the joint started jumping.

At the end of the set, President Nixon coaxed Ellington back to the platform and asked him to play. “I shall pick a name and see if I can improvise on it . . . something, you know, very gentle, graceful, and something like princess—Pat,” he replied. Then he sat down at the piano and improvised a pastel portrait of Pat Nixon, yet another of the on-the-spot musical miracles that he had been shaking out of his sleeve for years. Though he had only played two recitals without the full band, at the Museum of Modern Art in January of 1962 and Columbia University two years later, his rare solo essays were admired by connoisseurs. From “Reflections in D,” a study in chromatic ornamentation that he included on

The Duke Plays Ellington,

to “The Single Petal of a Rose,” the berceuse-like meditation in the veiled key of D-flat that he tucked into

The Queen’s Suite,

his tribute to Queen Elizabeth II, they rank among his most inspired moments on record, and “Pat,” which surfaced when the music performed at the White House in 1969 was commercially released on record in 2002, was one of the prettiest.

“One for each cheek, Mr. President”: At the White House, 1969. The elaborate party that Richard Nixon threw in honor of Ellington’s seventieth birthday did much to compensate for the embarrassment of his having been denied a Pulitzer Prize

When it was all over, he and Carney left for Oklahoma City. Medals of Freedom pay no bills, and Ellington was having trouble making ends meet, so much so that Russell Procope had quit the band briefly in 1968 after going unpaid for three weeks. Stanley Dance recalled a nervous morning when Ellington, who never arose before late afternoon for any reason short of a hotel fire, was awake at eight

A.M

., poring over stacks of papers as he lay in bed. “I’m trying to see where we can get some money from to pay the bus company,” he said. Mercer had watched the cash dry up, and he knew where much of it was going, for Ellington continued to play the grand seigneur, spending money that he no longer had on family and friends:

During those last horrible days . . . he had so many problems with taxes, also meeting expenses for rent and the number of people in the family he supported, it kept him to a point where basically he had about three possessions. He had a white overcoat, he had an electric piano he used to sleep with and a steak sandwich in his pocket. He never had much of anything that was really material. He had three pairs of pants he used on the road, some cashmere sweaters and a hat.

So he stayed on the road, playing wherever Joe Glaser sent him, making new albums for whatever labels cared to release them, and endorsing commercial products like Olivetti typewriters and Hammond organs (“Push a button, and you get rhythm”) to help keep the bus rolling. He had outlived virtually all of his Swing Era peers—only Count Basie, Woody Herman, Harry James, and Stan Kenton continued to lead full-time touring bands—but he also knew that his music, like theirs, had outlived its popular appeal. Rock and roll had taken over American pop culture in 1969, the year of

Abbey Road,

Easy Rider,

Let It Bleed,

Tommy

, and the Woodstock festival. Even Miles Davis, the most influential jazzman of the postwar era, embraced the new sounds with

In a Silent Way

. To do otherwise was to risk being written off as old-fashioned, and Ellington saw no alternative but to pay homage to the moment. Conscious of the commercial risks of looking his age, he had long worn his conked hair in a grotesque little ponytail that Charles Sam Courtney described as “pomade-shiny, streaked with gray and henna.” Now he upped the ante by donning ever more self-consciously trendy outfits and writing a hand-clapping gospel-rock number called “One More Time for the People” that he insisted on playing in the hope of making the people think that he was something other than a seventy-year-old whose tank was nearly out of gas. “If we keep playing that number, then the critics can stop wondering what to pan,” he told a friend.

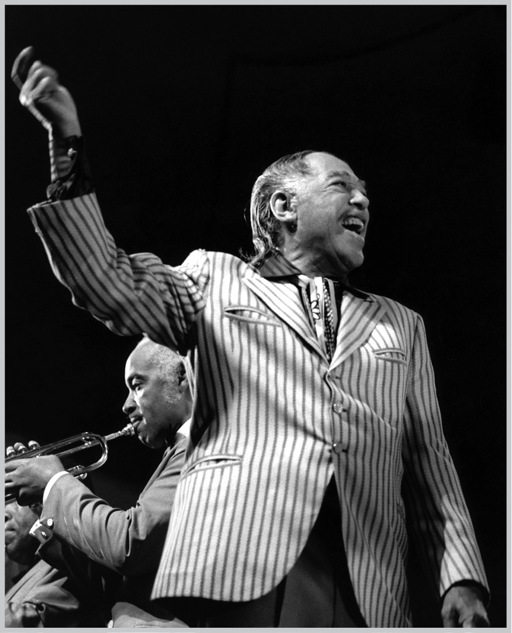

“It has nothing to do with taste”: Onstage with Mercer Ellington, 1971. Intensely aware that the baby boomers preferred rock to jazz, Duke Ellington sought late in life to cater to their tastes by playing arrangements of songs by the Beatles and dressing in gaudily “mod” outfits, sometimes with embarrassing results

Now, too, came the terrible and crushing losses, the first of which was the departure of Lawrence Brown, who quit in December of 1969, claiming that he had “lost all feeling for music” and had no desire ever again to play the trombone. Brown later said that he was “sick and tired of all of that hypocrisy, exploitation, deceit . . . everything that was going on” in the Ellington band. No doubt he was, since he had been complaining about it for as long as the youngest sidemen had been alive. For years, Joya Sherrill said, he “never got on the bus without saying, ‘I’m gonna leave this band.’” But the real reason for his sudden retirement, which he chose not to reveal save to friends, was that after decades of feuding, he and Ellington had finally gotten into a backstage fistfight, and his boss had knocked out his two front teeth.