Early Dynastic Egypt (21 page)

Netjerikhet is better known by the name preserved in the later king lists, Djoser. Unfortunately, this name—presumably the king’s

nbty

or

nswt-bỉty

name—does not appear on any contemporary monument or inscription, and the equation of Djoser and Netjerikhet (the king’s Horus name) depends on the much later Sehel Famine Stela (Barguet 1953: esp. 14, pl. III). Since later tradition also revered Djoser as the king for whom the Step Pyramid complex was built (Grimal 1992:65), there can be no doubt about the correctness of the identification. When the New Kingdom scribe drawing up the Turin Canon came to the name of Djoser, he changed the ink in his pen from black to red (Gardiner 1959: pl. II; Malek 1986:37). By writing the name of Djoser in red ink, he was indicating the special place held by that king in the minds of later generations of Egyptians. Despite the continuities between the end of the Second and the beginning of the Third Dynasty, the scribe was justified in recording the accession of Netjerikhet/Djoser as a significant milestone in Egyptian history. The king made a decisive break with the past, by abandoning for good the traditional royal burial ground of Abydos in favour of a site overlooking the capital (cf. Shaw and Nicholson 1995:149). This decision is likely to have been made for a variety of reasons. The rebellions in the north of the country recorded on the statue bases of Khasekhem may have been a factor. By siting the royal mortuary complex—the pre-eminent symbol of centralised authority—closer to Lower Egypt, the king may have been making a statement about royal control of the north. If the king now resided permanently at the capital, it would have been logical to site the royal tomb nearby. Furthermore, Netjerikhet may have had family ties with the Memphite area, since Manetho records that the Third Dynasty kings were from Memphis.

The mortuary complex of Netjerikhet at Saqqara is one of the most impressive monuments in the Memphite necropolis (Lauer 1936, 1939). It represents a staggering achievement, and remains one of the most important sources for Early Dynastic religion and kingship. The name of the king features most prominently on the six panels from the galleries beneath the pyramid and South Tomb (F.D.Friedman 1995). Lintels from the false doors framing the inscribed panels give the king’s complete titulary (Firth and Quibell 1935, II: pls 16, 39, 43), whilst boundary stelae from the complex are inscribed with the names of the king and female members of his family (Firth and Quibell 1935, II: pl. 87; Porter and Moss 1974:407; reconstructed by Lauer 1936:187, fig. 209). Seal- impressions with Netjerikhet’s

serekh

have also been found in the galleries beneath the North Court granaries (Firth and Quibell 1935, I: 141, figs 19–21) and beneath the pyramid itself (Lauer 1939:74, pl. XIX.9). Recently, some unique decorated blocks thought to derive from a gateway in the complex have been published (Hawass 1994). They feature the king’s

serekh

and a series of recumbent lions, the whole design framed by snakes.

The dominance of the Step Pyramid complex is something of a mixed blessing for ancient historians. It certainly highlights the reign of Netjerikhet as a period of great artistic, architectural and administrative innovation. However, it tends to obscure the king’s other accomplishments and the evidence for his activities in other parts of Egypt. Only fragments now survive of a decorated shrine from Heliopolis (W.S.Smith 1949:133–7, figs 48–53). The scenes in raised relief may be connected with the celebration of a Sed-festival and/or with the

ennead

(assembly of nine gods) worshipped at Heliopolis. Relief blocks from the temple of Hathor at Gebelein probably date to the

reign of Khasekhemwy; however, it is possible that they date to the beginning of the Third Dynasty, if the ‘archaic’ style of decoration is due more to the provincial origin of the work (W.S.Smith 1949:137). Although the royal burial ground at Abydos was abandoned after the death of Khasekhemwy, the region remained a location for high- status burials into the Third Dynasty. Mastaba K1 at Beit Khallaf (Garstang 1902) dwarfs even the Abydos and Hierakonpolis enclosures of Khasekhemwy. It yielded a large number of seal-impressions, most of them dating to the reign of Netjerikhet, including the sealing of Queen Nimaathap discussed above. One possibility is that mastaba K1 was her tomb. Other tombs were built at Beit Khallaf during the reign of Netjerikhet, though none of them equals K1 in size. A sealing of Netjerikhet was found in each of the mastabas K2, K3, K4 and K5 (Garstang 1902). These monuments may have belonged to minor members of Nimaathap’s family, perhaps the descendants of the First Dynasty royal family who still exercised local authority as governors of the Thinite region. The only other site within Egypt where Netjerikhet is attested is Elephantine. Four jar-sealings have been excavated from the eastern area of the town (Dreyer, in Kaiser

et al.

1987:108 and 109, fig. 13c, pl. 15c). Each bears the king’s

serekh

; one gives the titles of an official, ‘controller of the cellar and assistant in the magazine of provisions…of Upper and Lower Egypt, follower of the king every day’. A further sealing has been found more recently in the Old Kingdom debris of the eastern and southern sectors of the town (Leclant and Clerc 1993:250). At Saqqara, sealings of Netjerikhet have been found in three élite, private tombs (S2305 and S3518: Porter and Moss 1974:437, 448, respectively; Emery 1970:10, pl. XVII.l; G.T.Martin 1979:18, pl. 19.5), including the tomb of Hesira (Quibell 1913:3, pl. XXVIII.23), famous for its carved wooden panels.

By far the most significant development of Netjerikhet’s reign, aside from the construction of his mortuary complex, was the instigation of regular Egyptian activity in the Wadi Maghara, the turquoise mining area of the south-western Sinai. Whilst there is evidence for sporadic Egyptian involvement in the Sinai from Predynastic times, centrally organised expeditions to exploit the area’s mineral reserves, attested by rock-cut inscriptions, apparently began only in the early Third Dynasty (Gardiner and Peet 1952, 1955). It is possible that the administrative sophistication required to mount such long- distance enterprises was only developed as a result of the pyramid-building activity which characterised the Third Dynasty. Alternatively, state-sponsored activities outside the boundaries of Egypt proper may have been impossible during much of the Second Dynasty when the country seems to have been riven by internal tensions.

The Turin Canon gives Djoser a reign of just nineteen years. This seems rather brief, given the achievements of his reign. However, the Step Pyramid complex was left unfinished, and it is likely that the king died before his grand project could be completed.

Sekhemkhet

For once, the archaeological evidence and all the later king lists agree on the identity of Netjerikhet’s successor (Figure 3.5). His Horus name was Sekhemkhet, his name given in the king lists, Djeserty. The correspondence of the two names was proven by the discovery of an ivory plaque in Sekhemkhet’s step pyramid complex (Goneim 1957: pls LXV.B, LXVI). The plaque was engraved with the inscription

nbty srtỉ nh

.

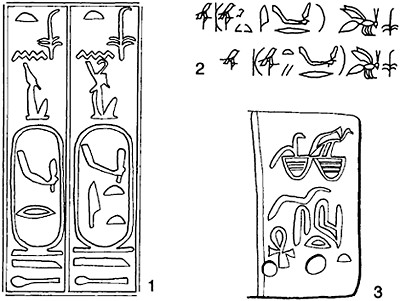

Figure 3.5

The Third Dynasty: a problem solved. A rare example of textual and archaeological sources in agreement: (1) cartouches of Djoser (Netjerikhet) and his successor ‘Djoser-teti’ from the king list in the tomb of Tjuneroy at Saqqara (after Gardiner, 1961: fig. 8); (2) corresponding entries from the Turin Royal Canon, naming Djoser’s successor as ‘Djoserty’ (after Gardiner 1959: pl. III); (3) the royal name from an inscribed ivory plaque found in the unfinished step pyramid complex of Sekhemkhet at Saqqara, giving the king’s ‘Two Ladies’ name Djesert(i)-ankh and thus confirming the identification of Sekhemkhet as Netjerikhet’s immediate successor (after Goneim 1957: pl. LXVI). Not to same scale.

The king’s mortuary complex is the principal monument to have survived from his reign (Goneim 1957). It seems that Imhotep, chancellor under Netjerikhet and fabled as the architect of his Step Pyramid complex, also had a hand in Sekhemkhet’s mortuary complex: a graffito on the northern enclosure wall of the Sekhemkhet complex names Imhotep (Goneim 1957:4, pl. XIII), although the context is unclear. The high quality of

workmanship in Sekhemkhet’s reign is eloquently attested by finds from his pyramid enclosure, particularly the set of gold jewellery discovered in the main corridor of the substructure (Goneim 1957: pls XXXI-XXXII

bis

).

Sekhemkhet continued the programme of expeditions to the Wadi Maghara instituted by his predecessor. A rock-cut inscription on a cliff above the valley shows the king smiting a Bedouin captive (Gardiner and Peet 1952: pl. I). (This inscription was once attributed to the First Dynasty king of a similar name, Semerkhet.) A seal-impression bearing the name of Sekhemkhet has been discovered recently in the Old Kingdom town at Elephantine (Leclant and Clerc 1993:250; Pätznick, in Kaiser

et al

1995:181 and 182, fig. 29a; Seidlmayer 1996b: 113). The sealing gives the titles of an official who was both ‘overseer of Elephantine’ and ‘sealer of gold of Elephantine’. The seal represents the earliest known occurrence of the town’s name (Egyptian

3bw

) (Seidlmayer 1996b: 113).

The Turin Canon assigns Djoser’s successor a reign of just six years. Given the unfinished nature of Sekhemkhet’s step pyramid complex – presumably the major construction project of his reign—and the paucity of other monuments dated to his reign, this figure seems reasonable (cf. Goedicke 1984).

Khaba

The Horus Khaba is attested at four, perhaps five, sites in Egypt. Eight stone bowls from a high-status mastaba at Zawiyet el-Aryan (Z500) in the Memphite necropolis are inscribed with the king’s

serekh

(Arkell 1956; Kaplony 1965:27, pl. VI, fig. 57; Dunham 1978:34, pls XXV-XXVI). The mastaba is located in a cemetery adjacent to the so-called ‘layer pyramid’, an unfinished royal mortuary complex of the late Third Dynasty (Dunham 1978). There is no evidence from the pyramid itself to link it with Khaba, but it is generally attributed to him on the basis of the inscribed stone bowls found nearby (cf. Stadelmann 1984:496; Edwards 1993:64).

In Upper Egypt, the name of Khaba has been found on sealings from Hierakonpolis and Elephantine (Figure 3.6). The Hierakonpolis sealing came from the Early Dynastic town, either from houses or from the Early Dynastic stratum under the Old Kingdom temple of Horus (Quibell and Green 1902: pl. LXX.1). The Elephantine sealing was excavated from the eastern town, and shows a divine figure (possibly the god Ash, connected with royal estates) holding a long sceptre, flanked by

serekh

s of Khaba (Dreyer, in Kaiser

et al.

1987:108 and 109, fig. 13.b, pl. 15.b). The inscription on the other side of the sealing is almost illegible, but does include the title

h3ti- ,

‘mayor’, one of the earliest references to this office. The

serekh

of Khaba is also inscribed on an unprovenanced diorite bowl in London’s Petrie Museum (Arkell 1956) and on another diorite bowl in a private collection, said to have come from Dahshur (Arkell 1958).

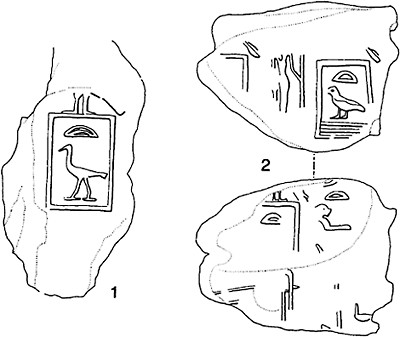

Figure 3.6

Ephemeral rulers, 2: Khaba. Sealings with the king’s

serekh:

(1) from the early town at Hierakonpolis (after Quibell and Green 1902: pl. LXX.1); (2) from the early town at Elephantine (after Dreyer, in Kaiser

et al.

1987:109, fig. 13.b).

We must admit that next to nothing is known for certain about the reign of Khaba. His

nswt-bỉty

and

nbty

names are unknown. Even his position within the order of succession has not been established beyond doubt, though he clearly reigned in the latter part of the Third Dynasty. Many scholars identify him as the penultimate king of the dynasty (for example, Baines and Málek 1980:36), though it has been suggested that Khaba was the Horus name of the last king, better known as Huni (Stadelmann 1984:496). This is because stone bowls incised with the name of a king are common in the First and early Second Dynasties but, otherwise, are not attested again until the reign of Sneferu. This tends to suggest that Khaba preceded Sneferu by only a short period. Moreover, the sealings of Khaba come from two sites where Huni erected small step pyramids. The coincidence of the Khaba sealings and these monuments suggests at least the possibility that Khaba and Huni were one and the same king. None the less, the general consensus identifies Khaba as one of Huni’s predecessors. In view of the evidence, discussed below, for the position of Sanakht within the Third Dynasty, and the close architectural similarity between Sekhemkhet’s unfinished pyramid and the one at Zawiyet el-Aryan,

Other books

Mia the Melodramatic by Eileen Boggess

New Boy by Nick Earls

Inherit the Word (The Cookbook Nook Series) by Gerber, Daryl Wood

No Time for Goodbye by Linwood Barclay

The Hit List by Ryan, Chris

Freddy Plays Football by Walter R. Brooks

Death is Forever by Elizabeth Lowell

A Great Game by Stephen J. Harper

A Pacific Breeze Hotel by Josie Okuly

Final Flight by Beth Cato