Early Dynastic Egypt (41 page)

Although ancient Egyptian royal names are notoriously difficult to translate—the individual elements comprising a name have been likened to a newspaper banner headline, rather than a grammatically correct sentence—insights into Early Dynastic kingship can be gained from an analysis of the Horus names of the first three dynasties. A survey reveals subtle developments in the type of epithet chosen, and thus in the message conveyed. Changes in the formulation of the Horus name (a Seth-name and a Horus-and- Seth-name are also attested from the late Second Dynasty) must reflect, to some degree, the changing emphasis of Egyptian kingship.

The Horus names of several First Dynasty kings express the aggressive authority of Horus, perhaps reflecting the coercive power of kingship at this early stage of Egyptian statehood. Names like ‘Horus the fighter’ (Aha), ‘Horus the strong’ (Djer) or ‘arm-raising Horus’ (Qaa) call to mind the warlike iconography of the earliest royal monuments from the period of state formation. They emphasise an authority based upon military might and the power of life and death. Amongst First Dynasty Horus names, only Semerkhet, ‘companion of the corporation’, makes a theological statement, expressing the

relationship between Horus and the other principal deities in the Egyptian pantheon. In this respect, it points the way to more sustained efforts at theological exposition in the Third Dynasty.

The emphasis in the Second Dynasty is rather different. Following periods of instability, the first and last kings of the dynasty were each faced with a task of renewal, and this is reflected in their Horus names: ‘Horus: the two powers are at peace’ (Hetepsekhemwy) and ‘Horus and Seth: the two powers have arisen; the two lords are at peace in him’ (Khasekhemwy-nebwy-hetep-imef). The other Second Dynasty Horus names express the ideal of kingship in more overtly theological terms: hence names such as ‘Horus, lord of the sun’ (Nebra), ‘Horus of divine nature’ (Ninetjer), and especially ‘Horus strong-willed, champion of

Maat

’ (Sekhemib-perenmaat). This last name is the earliest and most direct expression of the king’s principal role: to uphold Maat.

This trend continues into the Third Dynasty when the Horus names describe either the relationship between Horus and the other gods comprising ‘the corporation’ or the position of Horus as the god most intimately associated with Egyptian kingship. Thus, Horus is both the ‘(most) divine of the corporation’ (Netjerikhet) and the ‘(most) powerful of the corporation’ (Sekhemkhet), and has ‘arisen as a

ba

’ (Khaba). The king, as the incarnation of Horus, is ‘the strong protector’ (Sanakht) of mankind and the cosmos, and ‘high of the white crown’ (Qahedjet), the most exalted item in the royal regalia. The Horus names of the Third Dynasty kings comprise a miniature theological treatise on Horus, the king, their relationship to each other and to the wider pantheon. In this respect they echo the complex theology of the Pyramid Texts, some of which must date back to the Early Dynastic period.

The ‘Two Ladies’ title

The title

nbty,

the Two Ladies’ (Figure 6.5), emphasised the geographical duality of the Egyptian realm, but at the same time the enduring unification of the Two Lands in the person of the king. A similar concept is expressed in a circumlocution for the king found in one of the titles borne by Early Dynastic queens, ‘she who sees Horus-and-Seth’. The concept that the king embodied both gods highlights a fundamental role of kingship: the reconciliation of opposites in order to maintain the established order. The

nbty

name emphasised the geographical aspect of this balance.

The

nbty

name itself was written after the images of the two deities, the vulture and cobra. In one instance, on a label of Djet from mastaba S3504 at North Saqqara, the cobra is replaced by the red crown, demonstrating a very early association of the two (Gardiner 1958). Each goddess is depicted resting on a basket (

nb

); the two baskets form a pun on the title itself (

nbty

) (S.Schott 1956:56). The choice of Nekhbet and Wadjet to symbolise the two halves of the country seems to date back to the immediate aftermath of the unification. Elkab and Buto also represented the very different terrains of the Two Lands: the narrow river valley of Upper Egypt, running through barren desert on either side; and the wide expanses of flat, marshy land in the Delta. It had long been suspected that the towns themselves must have been important localities in the period immediately preceding the unification. Modern excavations have confirmed that this was indeed the case (von der Way 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1992; Hendrickx 1994).

The concept of the ‘Two Ladies’ is first met in the reign of Aha. An ebony label from the tomb of Neith-hotep (probably Aha’s mother) at Naqada shows the

serekh

of Aha facing a tent-like shrine, enclosing the signs

nbty mn

. There has been considerable debate about the meaning of this group. It may be the name of a king; more plausibly, it may be the name of the shrine itself, ‘the Two Ladies endure’ (Quirke 1990:23). In this case, the label attests the existence of the Two Ladies’, and their close connection with the kingship, from the very beginning of the First Dynasty; but it does not prove the existence of the Two Ladies’ title at this stage, nor does it have any bearing on the identification of the semi-legendary King Menes.

The element

nbty

first appears as a regular element of the royal titulary in the reign of Semerkhet (the element

nbwy

in Anedjib’s titulary may be seen as a precursor [S.Schott 1956:60]). Many of the Early Dynastic

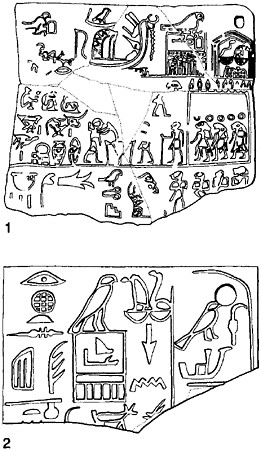

Figure 6.5

The Two Ladies. (1) The pairing of the vulture goddess Nekhbet and the cobra goddess Wadjet (known in Egyptian as

nbty,

‘the Two Ladies’) is first attested (top) on an ivory label of Aha from the royal tomb at Naqada (after Emery 1961:50, fig. 10). (2) The pairing of the two goddesses was adopted in the First Dynasty as one of the king’s principal titles, as shown here on an ivory year label of Qaa from Abydos (after Petrie 1900: pl. XVII.29). Not to same scale.

kings wrote the titles

nswt-bỉty

and

nbty

together, followed by a single name which thus served under both headings. An alternative interpretation sees the

nbty

element as part of the

nswt-bỉty

name, only later becoming a separate title in its own right (Müller 1938:51; S.Schott 1956; Quirke 1990:23).

Early Dynastic inscriptions record only a few distinctive

nbty

names; that is, those which differ from the king’s

nswt-bỉty

name. A

nbty

name,

sn,

is attested on a few inscriptions from the reign of Qaa. This may have the meaning ‘brother’, expressing the king’s closeness to the patron goddesses. A recently discovered year label of Qaa from his tomb at Abydos gives an otherwise unattested version of the king’s

nbty

name,

shtp(- nbty),

‘the one who pacifies (the Two Ladies)’ (Dreyer

et al.

1996:74, pl. 14.e). This seems to express the role of the king in placating the gods and in maintaining the harmony of opposites necessary for cosmic order. The Horus Sekhemkhet imitated his illustrious predecessor Netjerikhet in many ways, not least in the choice of his

nbty

name: an ivory plaque, found in one of the subterranean magazines of Sekhemkhet’s unfinished step pyramid, is inscribed

nbty srtỉ(- nh ).

The name

srtỉ(- nh

) is difficult to translate precisely, but it is clearly connected with the word

sr

and probably refers to the sacred nature of kingship. The word

sr

had added significance in Egyptian, conveying a sense of separateness. This sense that the king is set apart from the rest of humanity was expressed in concrete terms in the location and architecture of the Third Dynasty step pyramid complexes.

The

nswt-bỉty

title

The

nswt-bỉty

title was an innovation of Den’s reign, one of several important developments which characterise the middle of the First Dynasty. It has been suggested that the adoption of the new title coincided with the first occurrence of the joint ceremony of

h t nswt-bỉty,

‘the appearance of the dual king’, recorded on the Palermo Stone in the reign of Den (year x+3) (Godron 1990:180). The new title took second place in the royal titulary, coming immediately after the king’s Horus name. Whereas the Horus name remained the principal means of identifying the reigning king, the

nswt-bỉty

title and name often seem to have been used in secondary contexts (Quirke 1990:23). For example, inscriptions referring to buildings or boats named after the king use the

nswt- bỉty

(or

nswt-bỉty-nbty)

name.

The name itself followed the title

nswt-bỉty,

translated literally as ‘he of the sedge and bee’. The meaning of the title is complex and many-faceted. In bilingual inscriptions of

the Ptolemaic period, the Greek equivalent of

nswt-bỉty

translates as ‘king of Upper and Lower Egypt’. This has remained the traditional translation for

nswt-bỉty

, even though it is unlikely to have been the original sense. Rather, the recently suggested ‘dual king’ gives a better approximation of the true meaning (Quirke 1990:11). The title seems to have stressed the role of the king as the embodiment of all the dualities which made up Egypt and the cosmos according to the Egyptians’ world-view. Above all, perhaps, the dual title

nswt-bỉty

stressed the two different aspects of kingship, the divine and the human. The usual word for ‘king’ in ancient Egyptian was

nswt,

and this appears to have been the superior designation for the ruler (although it may simply have been an abbreviation of the full title

nswt-bỉty

[Quirke 1990:11]). In other contexts, especially administrative, the king might be referred to indirectly as

bỉty.

For example, the position of ‘king’s treasurer’ was designated by the title

h tmw-bỉty,

not

*h tmw-nswt.

The

nswt- bỉty

title ‘probably fused two hierarchically ordered words for king and aspects of kingship’ (Baines 1995:127). It seems likely that

nswt,

as the superior title, conveyed the divinity of the king, expressed in his role as the incarnation of Horus and earthly representative of the gods. (It is significant that the Egyptian word for ‘kingship’ is derived from

nswt

.) By contrast,

bỉty

may have indicated the king’s human aspect, especially his position as head of state and government (Ray 1993:70; Shaw and Nicholson 1995:153). The introduction of the

nswt-bỉty

title marks an important stage in the formulation of kingship ideology. Henceforth, emphasis was firmly placed upon the king’s role in binding together Egypt and the cosmos. Harmony of opposites is a theme which was given visual expression in some of the earliest monuments of kingship, particularly the ceremonial palettes from the late Predynastic period. With the introduction of the

nswt-bỉty

title in the reign of Den, this theme was brought into the royal titulary.

nswt-bỉty

names

After the title

nswt-bỉty

came a name which may also have been the king’s birth name (S.Schott 1956:76). It was certainly the name by which many kings were known in later annals and king lists. The

nswt-bỉty

title was often paired with the element

nbty,

after the introduction of the latter in the reign of Semerkhet. Peribsen was the first king to separate the two elements and use the

nswt-bỉty

title alone once more (S.Schott 1956:61), on a sealing from Abydos (Petrie 1901: pl. XXII.190).

Den’s

nswt-bỉty

name,

zmtỉ

(S.Schott 1956:60), appears on many contemporary inscriptions, especially the stone vessels found beneath the Step Pyramid. The name was also used on royal seals, frequently without reference to the king’s Horus name. It must, therefore, have had a significance of its own. It means ‘the two deserts’, referring to the eastern and western deserts which guarded the Nile valley on each side. It reinforces the message of the

nswt-bỉty

title: that the king’s rule extends over the whole of Egypt, east and west as well as north and south. Given the evidence that Den probably conducted a military campaign against the nomadic tribespeople of the eastern desert, his

nswt-bỉty

name may have had added resonance, proclaiming his intention to subdue Egypt’s desert borderlands and bring them under his yoke. An alternative reading of the name is

h 3stỉ

, translated as ‘the foreigner’ or ‘the Sinaitic’ (Godron 1990:21). It has been suggested that

Other books

Enlightening Delilah by Beaton, M.C.

The Wizard King by Dana Marie Bell

Lola and the Boy Next Door by Stephanie Perkins

A Stillness of Chimes by Meg Moseley

Influx by Kynan Waterford

Promise of Pleasure by Holt, Cheryl

Zorba the Hutt's Revenge by Paul Davids, Hollace Davids

The Girl With Hearts (Midtown Brotherhood #1) by Savannah Blevins

Scandalized by a Scoundrel by Erin Knightley