Edge of the Orison (9 page)

Read Edge of the Orison Online

Authors: Iain Sinclair

The adventures of childhood seem reasonable at the time. Somebody is in charge, this is how they behave; we lived to tell the tale. An Auster, co-owned in the era of photo albums featuring motorbikes (racing circuits, golf courses, ski slopes, punts, picnics), is itself a statement. Another theory: of private enterprise, freedom to travel, faith in the machine (cavalier disregard for diminishing fossil fuel reserves). Pipes, cigarettes, cigars. Hats, furs, car coats. German cameras to record (and retain) English scenes. Memory is competitive, siblings play back the same events in different ways. Robert Hadman calls up flights to northern France, casino towns, jollies. Anna associates the Auster with holidays in Cap d'Antibes: 1947 and the next five summers, two months at a time, rented villa in a discontinued resort (the ghosts of Scott and Zelda had decamped). Disputes with Madame the landlord. Swimming trials for ice-cream rewards. Morning lessons and the confinement of afternoon rests. Bill Hadman remembers the short, homemade boleros the children wore and the blocks of ice he had to carry from a flatbed truck into the cool room. There were no fridges. Now Anna understands the peculiar odour in the next property, the two Dutch women and their little weakness, opium. The family (absent father) might be accompanied by a BBC man, rather fey, who penned silly-season detective novels. In scrub woods, on a slope behind the villa, the

children discovered an unexploded shell (as tall as they were) and rolled it down the ramp towards their horrified parents. It was placed in an earthenware pot to await the police.

The highlight was always the gathering on the terrace – mother and children having driven down, the long haul, camping on farms – searching the sky for a first sight of the circling plane, the Auster. You heard the characteristic sound, this lawnmower of the clouds. A tip of the wing. A wiggle of the pipe clenched between the pilot's teeth. Mrs Hadman was off to collect her husband from Nice airport, leaving the kids with a helper, a woman friend. And the detective-story writer who had excellent French.

Cloudless skies, blue water. Bougainvillea, pine resin. It doesn't

fade: that colour. Warmth in the blood after seven years of Lancashire monochrome, shivering on windblown beaches, being asked to carry out impossible exercises from their father's cramped script. Schooled at home on scraps of unrelated information: foreign capitals, distance to Jupiter, king lists, vocabulary to be learnt by rote. The horror of struggling with Archimedes' principle. Powers often. Periodic tables learnt by mnemonics. ‘Little bees beat countless numbers of flies.’ Lithium, beryllium, boron… ‘Nations migrate always, sick people seek climbs.’ (You needed lithium to survive the experience.) Anna can never forget the terrifying squeak of chalk on the blackboard in the schoolroom. The challenge that would be sprung, months later, when the list was entirely forgotten. ‘Sick bees migrate always.’ Fear was the contract, the price of this privilege, French beach, rundown villa, coastal strip with its fascinating detritus of war.

On the day of their departure, bags packed, the children were marched to the beach to dive from a raft and collect weed from the seabed. Previous attempts had failed. Another spluttering return, empty-handed to the surface, and they'd be abandoned in France. Refusal was never an option. Pleasure was programmatic. A solitary dish of ice-cream you taste for the rest of your life. The triumphant child licks and luxuriates, the others are confined to quarters.

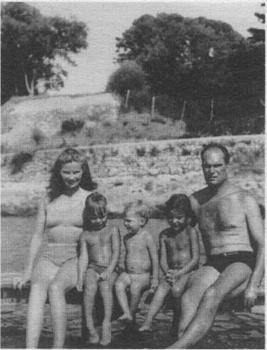

But they look happy in the yellowing photographs, the sexagenarian Hadmans who were naked kids on the French Riviera (protected from the sun by a quick dab of Nivea on the shoulders). Photographs have wrinkled, taking the blight that should have distressed their overexposed subjects. Older prints trap the family dead in eternal wedding parties. They grin or frown from sidecars and wingless planes. Large adults clambering into the scaled-down transport of Blackpool's Pleasure Beach. Revellers with drunken hats on flights that never leave the ground.

Black albums, interleaved with grey tissue, have a potent smell: sometimes camphor and closed bedrooms, sometimes a bonfire of autumn leaves. Dust of pressed flowers. Pages marked with faded ribbons. Sticky corners that have worked loose. Inscriptions in

white ink on brown paper. Anna in Antibes. Sitting on the sand, clutching her knees. Salt-sticky hair curled to the scalp. She is glossy and dark; a grave child with a private agenda (the look of Evonne Goolagong). Whooping cough defeated. Unexploded shells planted in terracotta pots. Beakers of pink Grenadine waiting on the terrace.

Around this time, before school or knowing children other than her immediate family, Anna flew with her father from Squire's

Gate, across England, to the Hadman farm in Glinton: a summer field, a bumpy landing like one of those French Resistance films with Virginia McKenna. Wings on struts; single prop loud enough to leave passengers, shaky from vibrations, deaf. ‘Everyone who talked to you was very far away.’ The soothing cup of tea on arrival rattles in your hand. Lips move but you can't hear what they say. Is this the same country? No passport control. No radio. Register your flight plan, follow major roads; when in doubt drop down to read the signs.

A flight recovered from a child's dream. Memories retained by a woman revisiting a place that is no longer there. She is confused, not by the parts that have disappeared, but by the buildings that are

almost

as they were: Auntie Mary's Balcony House, Uncle Lawrie's Red House, the post office, the school. Anna wants this to be what she wants, a slow life under pressing skies, a village organised around church and the passage of the seasons. Paths walked with cousins and aunts. With dogs.

Her father flew back. She stayed in Glinton. She wrote a letter to her brother William. ‘I am going to treasure island on Saterday, it is a play… You will be able to rite in ink one day… With very much love, Anna.’ Now she understands the distance between Blackpool and Glinton, she has witnessed it. The lurch, the vibration, the forward momentum of the Auster hauling itself over hedges and huts. She has never been on a commercial flight. Fields, she remembers, the pattern of them. But it's not the landscape, looking out on miniature farms and cars, it's reverie. Infiltrating that old dream of a life that is always there. Roads are white arms, rivers glitter. She is with her father, they can't speak. She's too deep in the seat, the leathery smell, to see out. It's not alarming. It takes a few days for the noise to fade.

She finds herself in a mirror country where, for the first time, other girls have her colouring, shape of eyes, generous mouth; sweet natures that snap, on the instant, flare and forgive. Photographs. Anna and her cousin Judy as children, on the farm: they could be sisters. Kittens. A keeshond called Woolfy. A strange,

floppy, hairless doll sagging from her grip: more like a thing used for practice by expectant mothers. A hooded and mittened child in the leafy lane outside the Red House. If Anna was lost and I had to search for a duplicate, I'd launch my quest in Peterborough. They are there still, in arcades, by the river, the ones with that Glinton look. Dark eyes that put the beam right through you. The Hadmans have stayed in one place for a long time.

After the Clare walk, our night in the Bell, we came back to Glinton. We had to do a last section to Clare's cottage in Northborough, the site of his discomfort, disorientation after the family's removal from Helpston. That short distance, three miles or so, undid the poet: from the circle of land edged by hills to the damp clutch of the Fens. A pull towards Market Deeping, Deeping St James and Crowland, instead of Stamford, with its bookshops, lively pubs, radical newspaper. Its mail coach connection to London. Northborough was a blot on the wrong side of the Maxey Cut. The wrong side of Glinton spire.

Edward Storey describes Northborough:

The darker, brooding, lonelier landscape was to be a fitting scene for his darker poems… The soil was different. The air was different. The sun appeared in a different quarter of the sky. It was a world which, deprived of limestone, could not grow many of his favourite wild-flowers, especially the orchis he loved to study. There were fewer trees and fewer birds. The hedges were, he tells us, ‘a deader green’, the sun was like ‘a homeless ranger’. Even the clouds and water lost their poetry, their deceptive innocence.

Glinton graves are scoured by wind and weather. Mary Joyce can be found, though we don't find her, not that day. But tucked in, sheltered at the west end of the church, is a fenced enclosure, teddy bears and flowers, kept up, dedicated to the memory of a dead child. A loud splash against the local bias towards grey, rain-coloured limestone.

Village history is summarised on a board: ‘Since 1900 the most prominent farming families in Glinton have been the Hadmans, Holmes, Neaversons, Reeds, Rollings, Sharpes, Titmans, Vergettes and the Websters.’ Vergettes and Titmans are well represented in the graveyard; lichen-licked to the colour and texture of dried mustard. Clustering together, they dominate this ground as, once, they dominated the surrounding fields. Grotesque stone heads rim the church. Overseers or magistrates watching for unseemly behaviour down below.

The fenced schoolyard brings it all back. After the original excursion, the Auster flight, Anna returned to Glinton, to Balcony House, in 1951. To stay with her father's sister, Mary Sugden. She found a letter to confirm the story that I was inviting her to tell.

I am havin a lovelly time. In the afternoon Antie Mary lets us take our shoes of. On the road the tar squeezes up. When I had my shoes, we were by the road and hapened to sit on some of the tar. Uncle Hubert got it of with some stuff out of a bottle.

Last night we had Judy to tea, after tea we all went for a walk with Judy's dog Chuffy. We had a long walk over fields and along the River far towards North Fen brige. We went through a field with very LUMPEY soil. The soil got into our sandals. Robert got left a very long way behind. He got nettle stings. I went back and tried to help him. He wouldnt come back for me but Judy gave him a piggiback. Some cows chased Chuffy and we all ran. Then a lady told us we were not supposed to be in those fields so we came back the way we came. Uncle Hubert met us on the way back and gave Robert a ride on his bike. I heard the clock in the tower strike eight when I got into bed.

My diary is packed every day.

Eight years old: Anna's first experience of being taught with other children. Her father had been sent to Mexico by ICI. Some woman was making her presence felt and Joan Hadman was required to fly out immediately. The three older children were

dispatched to Glinton, while the youngest girl, Susa, was left for three months with the gardener and his family.

School involved certain difficulties, such as religious knowledge: shades of St Benedict's vestry, John Clare and Mary Joyce. Mrs Rawsthorne, the school mistress, was tall, thin, grey; feared and respected in the village, lovely to the children. Anna's father, Geoffrey, had been one of her favourites: a person of character from the start (bane of future headmasters, inadequate instructors and minders). Anna had no experience of the Old Testament, unforgiving prophets who set bears on children. Beards who rode to heaven in fiery chariots. She remembers how prayers had to be copied out, with the threat of your books being taken in and inspected. Playtime was a relief: her younger brother, Robert, banished to the infants' enclosure, pressed a round red face against the fence, watching her. Mute and accusing.

The summer of 1951 is replayed as Anna watches current Glinton children moving around the yard. She had an affection, undeclared, for a boy called Maurice Waghorn. Another classmate, a ‘rough, rangy, village boy’ with red hair, Roy Garrett, pursued her with dogged intensity. The other kids chorused news of this infatuation. ‘Roy Garrett loves you.’ Heady times: the bruising dramas of village life, after fear-inducing lessons at home. Latin grammar, French verbs, lists of rivers in places she had never been.

Mary Annabel Rose Hadman: ‘Anna’. Three shots at fixing her, all wrong. The Mary part came from the Glinton aunt at whose house she was now staying. The Annabel sounds aspirational: tennis, riding, a Betjeman role that never took and was soon abbreviated. (William Hadman, her brother, named after his Glinton grandfather, would be sent to Marlborough, Betjeman's cordially loathed public school.) Because Mary comes first in the list it's the name on the cheque book; the unknown person asked for when the phone rings with official requests. Anna never understood the late Rose addition. Her father returned from registering the birth to inform his wife that he'd decided, on the spur, to make

an adjustment. (‘rose: as you grow i weaken’, wrote Tom Raworth in his Helpston poem.)