Einstein's Genius Club

Read Einstein's Genius Club Online

Authors: Katherine Williams Burton Feldman

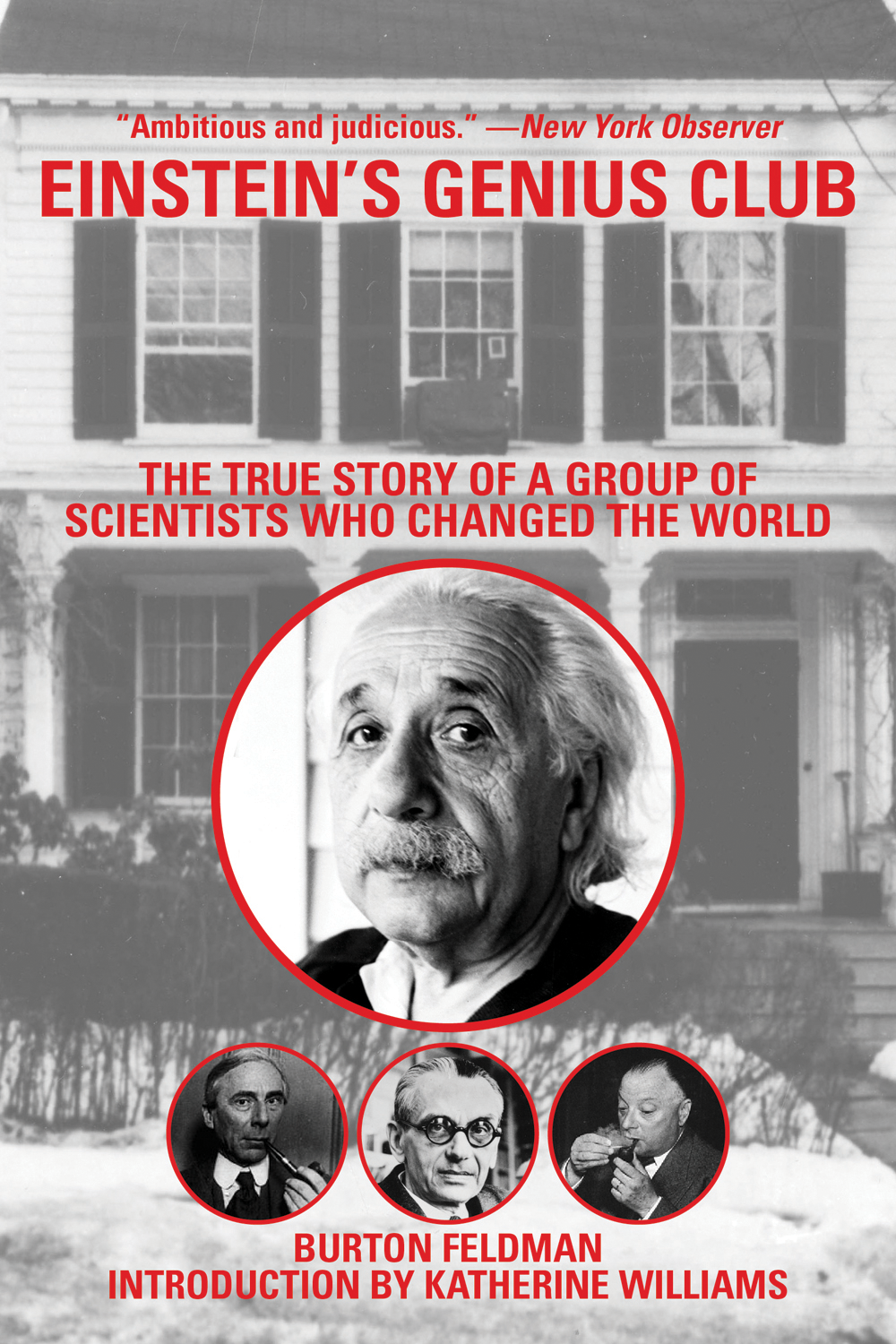

EINSTEIN'S GENIUS CLUB

A

LSO BY

B

URTON

F

ELDMAN

The Nobel Prize:

A History of Genius, Controversy, and Prestige

EINSTEIN'S GENIUS CLUB

THE TRUE STORY OF A GROUP OF SCIENTISTS

WHO CHANGED THE WORLD

BURTON FELDMAN

INTRODUCTION BY KATHERINE WILLIAMS

A

RCADE

P

UBLISHING

⢠N

EW

Y

ORK

Copyright © 2007, 2011 by Burton Feldman and Katherine Williams

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

[email protected]

.

Arcade Publishing® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at

www.arcadepub.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-342-3

Printed in the United States of America

To Peggy Feldman

ONTENTS

Russell: Aristocrat in Turmoil

Einstein and Unified Theory: Chasing the Rainbow

P

ART

4: B

EYOND

P

ATHOS

: O

PPENHEIMER

,

H

EISENBERG, AND THE

W

AR

Wartime Berlin, Winter 1943â44

Wartime Los Alamos, Winter 1943â44

Dangerous Knowledge: The New Security Order

Epilogue: The Projects of Science

NTRODUCTION

G

IVEN THE

D

AZZLING

H

ISTORY

of twentieth-century scientific discovery, the story of Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Kurt Gödel, and Wolfgang Pauli in conversation might seem trivial. Nothing really emerged from their meetings, as far as we can tellâneither momentous discovery nor earth-shattering weaponry.

Yet their confluence in the small town of Princeton, New Jersey, during the winter of 1943â44 is fascinating to ponder. They were giants divided by a generation. Einstein was schooled in classical physics; Russell began his career at the very dawn of mathematical logic. By the 1920s, when Pauli and Gödel came of age, certainties had dissolved. For Pauli, especially, the new quantum physics opened up endless possibilities for insight and production.

In this generational battle, Einstein fought desperately against the quantum mechanics so ably theorized by Pauli and his quantum brethren. Unable to refute the new physics, Einstein retreated into what now seems a doomed search for a unified theory. To his contemporaries, it seemed daft, even obstructionist. His failed search illustrates the pathos of science. For scientists, as for athletes, age does not correlate with creativity. The poet may begin a

long career with an apprenticeship of pastoral poetry, progressing finally to the noble epic, a trajectory known as Virgil's wheel. But science and mathematics are notoriously the provinces of youth.

As Einstein fought his battle in the world of physics, history was busy transforming how physics worked. World War II turned theoretical physics into a race for the ultimate weapon. Robert Oppenheimer, once a student of Pauli, headed the project in America. Werner Heisenberg, Pauli's friend and partner in the founding of quantum mechanics, was integral to Germany's effort. Inevitably, the bomb conferred on physics both prestige and peril. It took a soldier to coin the phrase “military-industrial complex.” Well before Eisenhower's words of warning, physicists understood their plight. The war, said the scientist and novelist C. P. Snow in a speech on morality and science, turned physicists into “soldiers-not-in-uniform.”

The pretext for this book is the gathering of four great minds in an academic backwater during a war that would change science forever. “I used to go to [Einstein's] house once a week to discuss with him and Gödel and Pauli,” wrote Russell in his

Autobiography

. That these meetings occurred is generally accepted by the biographers of Einstein, Russell, and Pauli. However, as with all things human, there is disagreement, and to ignore contrary evidence would be unseemly, not to mention unscholarly. Thus, against Russell's recollection of those meetings at 112 Mercer Street, we must cast some doubtâthat is, uncertainty of a mundane, rather than quantum, sort. Russell himself, speaking on the BBC in 1965, reported that in Princeton, Einstein “arranged to have a little meeting at his house once a week at which there would be some one or two eminent physicists and myself.” No mention was made of Gödel. Only in his

Autobiography

does Russell assert that he, Einstein, Pauli,

and

Gödel met regularly.

In 1971, Kurt Gödel learned of Russell's claim and drafted (but never sent) a rebuttal of sorts to a friend: “[t]he passage gives

the wrong impression that I had many discussions with Russell, which was by no means the case (I remember only one)â¦.” More pointed was Gödel's acerbic retort to Russell's assertion in the same passage that “Gödel turned out to be an unadulterated Platonistâ¦.” Gödel responded, “[My] platonism is no more âunadulterated' than Russell's own in 1921.” As we shall see, Russell and Gödel enjoyed a tangled relationshipâone that might have encouraged exaggeration about the question of their meeting from either man. It is possible, even likely, that Gödel turned up at Einstein's rather less than Russell's remark suggests, and equally possible that he showed up more than once.

Who was in attendance and when will forever be a matter of conjecture, as must our thoughts on what might have been said, beyond Russell's few (easily assailable) memories. More fascinating is the contextâcultural, theoretical, biographical, and historicalâof those meetings. The crosscurrents that made up this context are the subject of this book.

Finally, as must be obvious, the perspective of this book is not that of a scientist. Some might argue that the history of science is better left to scientists. For better or for worse, however, nonscientists are enthralled by that richly creative, densely coded worldâbeyond our grasp as laypersons, yet so enveloping of our lives.

To elucidate major characters and relevant concepts, we provide below brief biographical sketches and a glossary of terms. Terminology in boldface is cross-referenced in the Glossary.

LBERT

E

INSTEIN

(1879â1955)

With the publication of his theory of

general relativity

, Einstein, already well known among physicists, became world famous. No more ubiquitous a face has ever represented science in the popular imagination. Almost instantly, Einstein turned his fame into a

platform for political and humanitarian causes: internationalism, support for Israel, antifascism, civil rights, socialism. At the end of his life, with Russell, he made a final plea for world peace.

Best known among Einstein's works are the two relativity theories: the

special theory of relativity

(1905), which introduced the notion of spacetime, and the

general theory of relativity

(1916), which explained gravitation. In his “miracle year” of 1905, Einstein wrote a total of four papers, including that proposing special relativity. Ironically, it was not for either theory of relativity, but for the first of his 1905 papers that Einstein won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physics. That paper, on the photoelectric effect, was an inaugural step in the development of

quantum mechanics

, much to Einstein's chagrin. He spent most of his later years in a failed search for a

unified theory

based not on quantum mechanics, but on relativity.

ERTRAND

R

USSELL

(1872â1970)

Best known for his political activism, Bertrand Russell played a major role in the development of twentieth-century analytical philosophy. At Cambridge, he majored in mathematics and scored well enough on the feared “tripos” exams to be ranked among the first division “wranglers.” That Russell was able to bridge such utterly disparate worlds speaks as much to the restlessness of his intellect as to its power.

Russell's startling discovery in 1901 of a paradox that would bear his name,

Russell's paradox

(the conundrum posed by imagining a set of all sets that are not members of themselves), launched him into a decade's worth of work. In 1903, he published

The Principles of Mathematics

, precursor to the much longer

Principia Mathematica

, written with Alfred North Whitehead and published in three parts from 1910 to 1913. This latter work broke philosophical ground by promoting mathematical logic, or

logicism,

and by introducing a theory of types and a powerful notation system. For the first time, mathematically based logic made its way into the mainstream of philosophy, long dominated by metaphysics and epistemology.