Eleven

Authors: Patricia Highsmith

Eleven

BOOKS BY

PATRICIA HIGHSMITH

NOVELS

Strangers on a Train

The Blunderer

The Talented Mr. Ripley

Deep Water

A Game for the Living

This Sweet Sickness

The Two Faces of January

The Glass Cell

A Suspension of Mercy

Those Who Walk Away

The Tremor of Forgery

Ripley Under Ground

A Dog’s Ransom

Ripley’s Game

Edith’s Diary

The Boy Who Followed Ripley

People Who Knock on the Door

Found in the Street

Ripley Under Water

SHORT STORIES

Eleven

The Animal-Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder

Little Tales of Misogyny

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind

The Black House

Mermaids on the Golf Course

Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes

ELEVEN

Patricia Highsmith

Copyright © 1945, 1962, 1964, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970

by Patricia Highsmith

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

“The Birds Poised to Fly,” “The Terrapin,” “Mrs. Afton, among thy Green Braes” (as “The Gracious, Pleasant Life of Mrs. Afton”), “Another Bridge to Cross,” and “The Empty Birdhouse” all originally appeared in

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine;

“The Snail-Watcher” originally appeared in

Gamma;

“When the Fleet Was in at Mobile” originally appeared in

London Life;

“The Quest for

Blank Claveringi”

originally appeared in slightly altered form in the

Saturday Evening Post

as “The Snails”; “The Cries of Love” originally appeared in

Women’s Journal;

“The Heroine” originally appeared in

Harper’s Bazaar;

and “The Barbarians,” copyright © 1968 by P. Highsmith and Agence Bradley, was originally published in French in No. 17 of

La Revue de Poche

, published by Robert Laffont, and in English in

Best Mystery Stories

edited by Maurice Richardson,

Introduction and Selection copyright © 1968 by Faber & Faber.

Originally published in Great Britain in 1970 by William Heinemann Ltd.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Highsmith, Patricia

Eleven.

Contents: The snail watcher—The birds poised to fl y—The Terrapin—[etc.]

I. Title.

PS3558.1366E44 1989 813’.54 89-17648

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9551-7

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

11 12 13 14 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Alex Szogyi

CONTENTS

Foreword by Graham Greene

Stories by Patricia Highsmith: The Snail-Watcher

The Birds Poised to Fly

The Terrapin

When the Fleet was in at Mobile

The Quest for

Blank Claveringi

The Cries of Love

Mrs. Afton, among thy Green Braes

The Heroine

Another Bridge to Cross

The Barbarians

The Empty Birdhouse

FOREWORD

by Graham Greene

Miss Highsmith is a crime novelist whose books one can reread many times. There are very few of whom one can say that. She is a writer who has created a world of her own—a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each time with a sense of personal danger, with the head half turned over the shoulder, even with a certain reluctance, for these are cruel pleasures we are going to experience, until somewhere about the third chapter the frontier is closed behind us, we cannot retreat, we are doomed to live till the story’s end with another of her long series of wanted men.

It makes the tension worse that we are never sure whether even the worst of them, like the talented Mr. Ripley, won’t get away with it or that the relatively innocent won’t suffer like the blunderer Walter or the relatively guilty escape altogether like Sydney Bartleby in

A Suspension of Mercy

. This is a world without moral endings. It has nothing in common with the heroic world of her peers, Hammett and Chandler, and her detectives (sometimes monsters of cruelty like

the American Lieutenant Corby of

The Blunderer

or dull sympathetic rational characters like the British Inspector Brockway) have nothing in common with the romantic and disillusioned private eyes who will always, we know, triumph finally over evil and see that justice is done, even though they may have to send a mistress to the chair.

Nothing is certain when we have crossed

this

frontier. It is not the world as we once believed we knew it, but it is frighteningly more real to us than the house next door. Actions are sudden and impromptu and the motives sometimes so inexplicable that we simply have to accept them on trust. I believe because it is impossible. Her characters are irrational, and they leap to life in their very lack of reason; suddenly we realize how unbelievably rational most fictional characters are as they lead their lives from A to Z, like commuters always taking the same train. The motives of these characters are never inexplicable because they are so drearily obvious. The characters are as flat as a mathematical symbol. We accepted them as real once, but when we look back at them from Miss Highsmith’s side of the frontier, we realize that our world was not really as rational as all that. Suddenly with a sense of fear we think, “Perhaps I really belong

here

,” and going out into the familiar street we pass with a shiver of apprehension the offices of the American Express, the center, for so many of Miss Highsmith’s dubious men, of their rootless European experience, where letters are to be picked up (though the name on the envelope is probably false) and travellers’ cheques are to be cashed (with a forged signature).

Miss Highsmith’s short stories do not let us down, though we may be able sometimes to brush them off more easily because of their brevity. We haven’t lived with them long enough to be totally

absorbed. Miss Highsmith is the poet of apprehension rather than fear. Fear after a time, as we all learned in the blitz, is narcotic, it can lull one by fatigue into sleep, but apprehension nags at the nerves gently and inescapably. We have to learn to live with it. Miss Highsmith’s finest novel to my mind is

The Tremor of Forgery

, and if I were to be asked what it is about I would reply, “Apprehension.”

In her short stories Miss Highsmith has naturally to adopt a different method. She is after the quick kill rather than the slow encirclement of the reader, and how admirably and with what field-craft she hunts us down. Some of these stories were written twenty years ago, before her first novel,

Strangers on a Train

, but we have no sense that she is learning her craft by false starts, by trial and error. “The Heroine,” published nearly a quarter of a century ago, is as much a study of apprehension as her last novel. We can feel how dangerous (and irrational) the young nurse is from her first interview. We want to cry to the parents, “Get rid of her before it’s too late.”

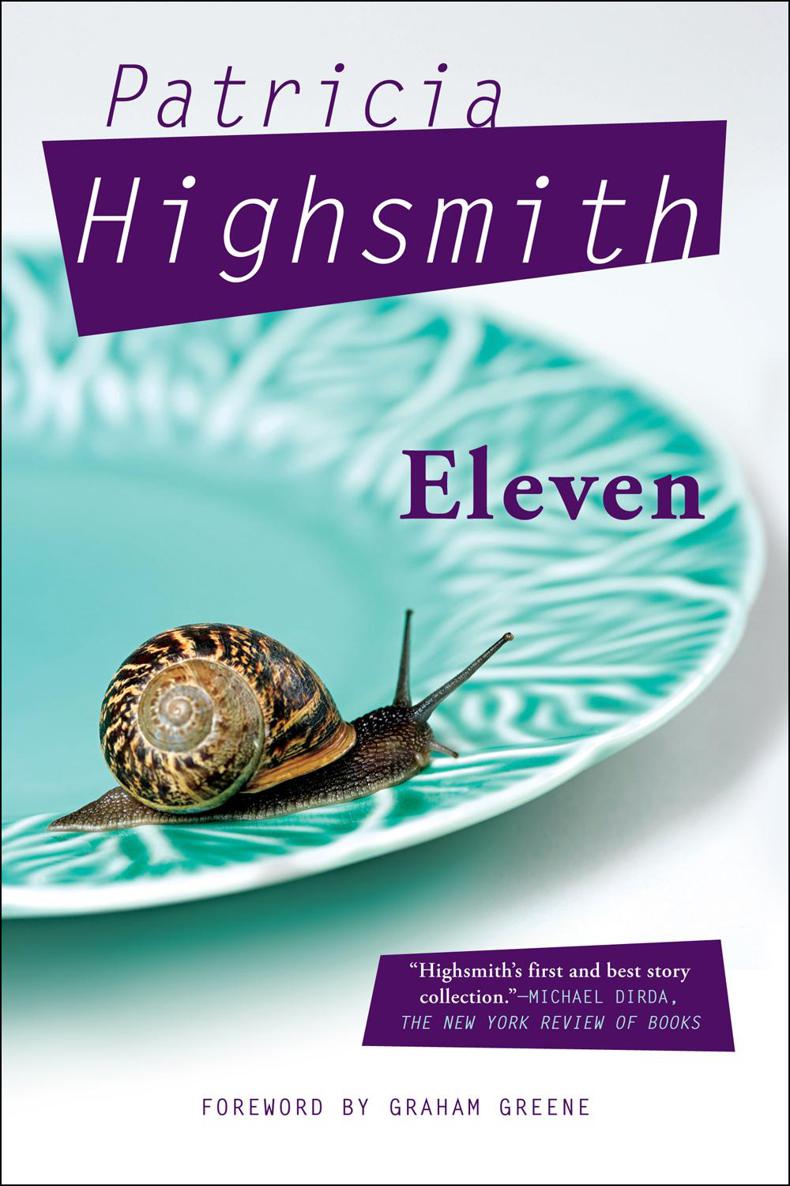

My own favorite in this collection is the story “When the Fleet was in at Mobile” with the moving horror of its close when all we had foreseen was a simple little case of murder—here is Miss High-smith at her claustrophobic best. “The Terrapin,” a late Highsmith, is a cruel story of childhood which can bear comparison with Saki’s masterpiece, “Sredni Vashtar,” and for pure physical horror, which is an emotion rarely evoked by Miss Highsmith, “The Snail-Watcher” would be hard to beat. Mr. Knoppert has the same attitude to his snails as Miss Highsmith to human beings. He watches them with the same emotionless curiosity as Miss Highsmith watches the talented Mr. Ripley:

Mr. Knoppert had wandered into the kitchen one evening for a bite of something before dinner, and had happened to notice that a couple of snails in the china bowl on the draining board were behaving very oddly. Standing more or less on their tails, they were weaving before each other for all the world like a pair of snakes hypnotized by a flute player. A moment later, their faces came together in a kiss of voluptuous intensity. Mr. Knoppert bent closer and studied them from all angles. Something else was happening: a protuberance like an ear was appearing on the right side of the head of both snails. His instinct told him that he was watching a sexual activity of some sort.

G.G.

THE SNAIL-WATCHER

When Mr. Peter Knoppert began to make a hobby of snail-watching, he had no idea that his handful of specimens would become hundreds in no time. Only two months after the original snails were carried up to the Knoppert study, some thirty glass tanks and bowls, all teeming with snails, lined the walls, rested on the desk and windowsills, and were beginning even to cover the floor. Mrs. Knoppert disapproved strongly, and would no longer enter the room. It smelled, she said, and besides she had once stepped on a snail by accident, a horrible sensation she would never forget. But the more his wife and friends deplored his unusual and vaguely repellent pastime, the more pleasure Mr. Knoppert seemed to find in it.

“I never cared for nature before in my life,” Mr. Knoppert often remarked—he was a partner in a brokerage firm, a man who had devoted all his life to the science of finance—“but snails have opened my eyes to the beauty of the animal world.”