ELIXIR (8 page)

Authors: Gary Braver

“I was doing life-cycle studies.”

“Really? For nearly one fiftieth the price you could have gotten mice with twice the life span. What the hell was the rush?”

“You’re the one who insisted we couldn’t depend on raw stock and needed to find a synthesis.”

“Uh-huh. Then what about these chemical orders? You purchased organics that have nothing to do with apricots or any other interests of this lab. Like on September 23 five years ago, eighteen liters of acetonitrile.”

“It’s a solvent for extracting the toxogen out of the apricot pits.”

“Is that right? Well, my chemistry’s a little rusty, so I checked. And everybody and his brother said that the solvent of choice is ethanol, not acetonitrile—which, as you well know, is used in organic procedures.” He adjusted his glasses, feeling very clever. “Then in December’84, seventyfive grams of L-N5 iminoethyl ornithine, and three months later a total of twenty liters of hexamethylphosphamide. And before you try and fudge up another answer, I checked and, lo and behold, nobody has a fucking clue why you’d need such fancy organics. In fact, HMPA is a goddamn carcinogenic which, by the way, cost us two thousand dollars.” He slapped down the inventory. “In fact, you’ve been ordering some rather strange materials ever since we sent you to Papua New Guinea back in 1980. You want to tell us just what the hell you’ve been doing in this lab for the last seven years while nobody was looking?”

They both stared at him for an explanation.

After a long moment, Chris said, “Nothing that matters.” He got up to leave.

But Quentin continued. “Then what about that conference on neurology and gerontology at Yale last November? Two days you were supposedly taking as sick days?”

“You’ve been spying on me. I don’t believe it.”

“Believe it,” Quentin said. “And believe it that misuse of company property and the misappropriation of funds is a criminal offense tantamount to stealing.”

Chris moved to the door.

“Well, maybe this will tell me.” Quentin was holding a black, bound ledger containing Chris’s notes on the tabukari elixir and its effect on his animals all the way back to 1980. He had broken into locked files in Chris’s office.

“And before you declare it’s personal property, let me remind you of your contract which reads: ‘All research material including equipment, animals, procedures, patents, inventions, discoveries,

and

notes are private property of Darby Pharmaceuticals.’ Do I make myself clear?”

and

notes are private property of Darby Pharmaceuticals.’ Do I make myself clear?”

A photocopy of Chris’s notes sat in front of Ross, who stared at Chris silently and without expression.

“And by the way,” Quentin continued, his face all aglow, “that mouse that died horribly a few weeks ago? Well, I checked the files and found he was purchased over six years ago—I repeat, six years ago. Now, I don’t know much about mice, but that struck me as unlikely, so I called Jackson and they confirmed that the original order of twenty such mice was placed in 1980. When I told them it was the same mouse, they said that was outright impossible because its life span was eleven months. There had to be some mistake because no mouse under the sun—no matter what breed or hybrid—lives six friggin’ years.”

They stared at him for an answer. “So what do you want?”

“What we want is for you to sit down and tell us all about your

tabukari

elixir.”

tabukari

elixir.”

“

A

m I being fired or not?”

A

m I being fired or not?”

They had read everything in his log. The entire medical history of his mice was in those notes, including Methuselah’s—six years of secret employment at Darby. If they wanted to, he could be out the door and facing charges of grand larceny.

“Fired?” Ross Darby stood up and came around his desk. “If you’ve developed something that’s multiplied the lifespan of mice, I want to know what it could do for humans. And I want you to find out. In fact, I’d like you to work on it full time.”

Christ! The genie was out of the lamp, and they wanted him to dance with it. “What about Veratox?”

“It’s quite clear the synthesis won’t work, and we’ve spent more than enough money to find out. We appreciate your efforts, but these things happen.”

“We still have another shipment of raw stock coming, no?”

“I need not get into it, but we don’t.” Ross was being evasive.

That explained the stoical attitude. Veratox was a bust, and Chris’s elixir had fallen into their laps to make up the losses.

“So,” Ross sang out, “what can it do for humans?”

Chris glanced at Quentin, who sat back waiting for him to spill. If he resisted or protested, they could still fire him, retaining his notes and the contents of his lab. Which would mean his genie would be dancing with someone else. “I don’t know.”

“Then how did you know about its longevity powers?”

“Rumors from New Guinea villagers.”

“Such as?”

He measured his words. The exposure was too sudden. “That it can retard the aging process.”

But Chris said nothing about Iwati. Neither did his name appear in the notes nor speculations about how the stuff might double or triple human lifespan or more. Only pharmacological and biological history of his mice—dosages, procedures, vital signs, blood and tissue chemistry, neurophysiology, and so forth.

“Well, I’m curious why all the secrecy,” Darby said. “You worked on it since 1980 and never breathed a word.”

“It didn’t strike me as profitable research given the limitations.”

“Not while you were here, that is,” Quentin said.

“Pardon me?”

Quentin’s face had a look of cagey cleverness he used to impress Darby. “I’m just wondering if you kept everything under wraps so you could perfect the stuff, then jump ship with the patent to start your own company.”

“Quentin, I’m a biologist, not a crackerjack entrepreneur like yourself.”

“I’m not interested in motives,” Ross interjected. “You’ve developed a compound that’s multiplied the lifespan of mice. That’s one hell of a breakthrough. And that’s what I’d like you to develop for us. Are you interested?”

To Chris, Ross Darby was the kind of businessman Ayn Rand would have swooned over. In less than twenty years he had taken his company out of his garage and into this multimillion-dollar complex. “Sure.”

“You mentioned limitations.”

“Accelerated senescence, rapid aging—what afflicted Methuselah.”

“Then its elimination should be a prime objective,” Ross said. “I have to admire you for pulling it off without notice. What bothers me is what that says about the quality of our bookkeeping.” He glanced at Quentin. “I’d like to see these mice, if you don’t mind.”

Chris took them to the back lab and the cages of mice, each hooked up at the skull to supplies of tabulone.

“You’ve invested half a dozen years and increased the lifespan of mice by a factor of six, so you must see hope for the human race.”

“Find the right chemicals,” Chris said, “and there’s no reason we can’t extend our warranties without limit—like these guys”

Ross studied the mice as if he were glimpsing magical creatures. “An appealing prospect, especially when you’re my age.”

“We’ve got a huge baby boomer generation out there eating their oat bran and jogging their asses off,” Quentin piped in. “We’re talking about a billion-dollar molecule.” His face glowed red at the prospect.

“What’s the composition?” Ross asked.

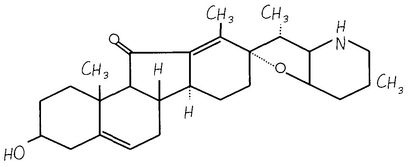

Chris opened his log notes to a ring diagram he had drawn.

Ross studied it. “A steroidal structure, except the C and D rings are reversed. I’ve not seen anything like it before.”

“I doubt anybody has,” Chris said. What made the compound unique was the spiral ring system—two rings coming off a common carbon atom, something not found in steroidal structures.

“What’s the plant?”

“A vine with small orchidlike flowers. I’m told it grows nowhere else in the world.”

“That’s what they said about the apricots,” Ross muttered. He studied the diagram.

“Where did you get the elucidation and synthesis done?” Ross was concerned that outside labs could compromise Darby’s exclusive patent on the compound, especially if the molecular profile got out. But Chris had anticipated all that. Without revealing its potentials, he had gotten analyses done at MIT, Northeastern University, and private labs without incurring interest. In his favor was the fact that nobody did steroid research anymore.

Darby stared at the clear liquid in the feeder tubes. “You’ve discovered a molecule that puts the cellular clock for mice on slow-mo. If you make it work for human beings, you’ll have the fountain of youth.”

“The operative word is

if.

Disconnect those tubes, and they’ll age to death before your eyes.”

if.

Disconnect those tubes, and they’ll age to death before your eyes.”

Ross eyed a mouse in the nearest cage, its skull sporting electrodes like a tiny diver’s helmet. “How old is this one?”

“Chronologically, sixty-two months. Biologically, I haven’t got a clue. Like most animals, mice don’t age in any noticeable way. They just get bigger. And smarter. Their cognitive powers have measurably heightened.”

And in his mind Chris saw his father in two different shoes, tearing up as he struggled to find the right word … to recall his son’s name. To block the fog that was slowly closing in.

“What do you think triggers this accelerated senescense?”

“I don’t know, but my gut feeling is that it’s in the molecule itself. It’s huge, which means the problem might be in the binding sites. Maybe something in the compound attaches to neuroreceptors and blocks the natural process of aging, and once it’s withdrawn the conditions causing senescence are heightened. Or maybe it works directly on the DNA sequence.”

“Any rumors of people rapidly aging in New Guinea?”

“None I know of.”

The intensity on Ross’s face said he was becoming convinced of grand possibilities. “The first step will be to get a patent on it. That’s essential.”

Because secrecy was essential they would have to apply for a “composition of matter” patent rather than a “use” patent to avoid stipulating the compound’s application as an anti-aging drug. Chris knew that the senescence effects would never pass FDA.

“What will it take to do the job?” Ross asked.

Chris was ready for him, and he ticked off the contents of his fantasy lab: High-speed computers with elaborate imaging software, nuclear magnetic resonance equipment, mass spectrometers, and so on. Ross snapped his fingers for Quentin to take it all down.

“Also, geneticists, pharmacists, physical chemists with pharmacology backgrounds. I can give you names. And test animals, especially rhesus monkeys—very old ones and virus-free.”

When he finished, Quentin looked at the list he had taken down. “You’re talking

major

capital investment.”

major

capital investment.”

“And it may not be successful,” Chris added.

“But I think you’re on to something extraordinary,” Ross said. “So we’ll do whatever it takes. I want you to put together the best team and lab that money can buy.”

Chris nodded, amused how in less than two hours he had passed from company crook to messiah. “I’ll do my best.”

“And the sooner the better,” Darby said. “I’m just a couple years this

side of my own warranty. You get it to work on old monkeys, and I’m next in line.”

side of my own warranty. You get it to work on old monkeys, and I’m next in line.”

“If this works,” Quentin said, “you’ll be more famous than God and twice as rich.”

Chris smiled. Fame and personal wealth were the last of his interests. He was by nature a private person and making enough of a salary to afford his and Wendy’s needs. Yes, it would be nice to have a few extra thousand, what with a child on the way and Wendy’s decision to take an extended maternity leave from teaching. But sudden wealth would only add an unnecessary edge of anxiety, like what put those Rocky Raccoon rings around Quentin’s eyes. Maybe it was no longer fashionable, but he was a scientist motivated solely by intellectual challenges, not financial ones. Even if he could afford otherwise, he preferred L. L. Bean to Armani, a Jeep to a Mercedes, and vacations at Wendy’s family lodge in the Adirondacks to

chateaux

on the Riviera.

chateaux

on the Riviera.

Ross had one more question before they left. “Does anybody else know about this? Colleagues or friends?”

“Just my wife.”

“Good,” Darby said, “and let’s keep it that way because if word leaks that we’re putting our resources into an anti-aging drug, the media will be on us like vultures and competitors will be scrambling to learn what we’ve got. Think of this as our own Manhattan Project.”

Later, while driving home, Darby’s words buzzed in Chris’s head. It wasn’t the demand for secrecy that bothered him—he was used to that. It was recollection of the first words of Robert Oppenheimer moments after the original Manhattan Project made a ten-mile-high column of radioactive smoke over Almagordo:

“I have become Death.”

“I have become Death.”

Other books

Life For a Life by T F Muir

Volcker by William L. Silber

Christmas at Jimmie's Children's Unit by Meredith Webber

Wanderlust: A Holiday Story (A Heroes and Heartbreakers Original) by French, Kitty

All for a Song by Allison Pittman

The Pricker Boy by Reade Scott Whinnem

In the Belly of the Elephant by Susan Corbett

Dutch Shoe Mystery by Ellery Queen

Cough by Druga, Jacqueline

Hope Farm by Peggy Frew