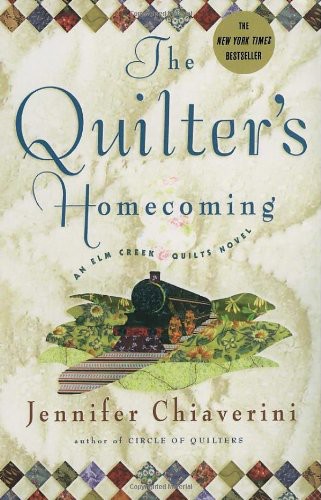

Elm Creek Quilts [10] The Quilter's Homecoming

Read Elm Creek Quilts [10] The Quilter's Homecoming Online

Authors: Jennifer Chiaverini

Tags: #Historical, #Adult

Circle of Quilters

The Christmas Quilt

The Sugar Camp Quilt

The Master Quilter

The Quilter’s Legacy

The Runaway Quilt

The Cross-Country Quilters

Round Robin

The Quilter’s Apprentice

Elm Creek Quilts:

Quilt Projects Inspired by the Elm Creek Quilts Novels

Return to Elm Creek:

More Quilt Projects Inspired by the Elm Creek Quilts Novels

Contents

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2007 by Jennifer Chiaverini

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

S

IMON

& S

CHUSTER

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

DESIGNED BY LAUREN SIMONETTI

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chiaverini, Jennifer.

The quilter’s homecoming : an Elm Creek quilts novel / Jennifer Chiaverini.

p. cm.

1. Quilting—Fiction. 2. Quiltmakers—Fiction. 3. Quilts—Fiction. 4. Pennsylvania—Fiction. 5. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3553.H473Q57 2007

813’.54—dc22

2006050580

ISBN-10: 1-4165-5712-1

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-5712-8

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

To Nan Bawn,

Quilt Maker,

Book Lover,

Friend,

and Honorary Elm Creek Quilter

I am very grateful to Denise Roy, Maria Massie, Rebecca Davis, Annie Orr, Aileen Boyle, Honi Werner, Melanie Parks, and David Rosenthal for their ongoing support for—and contributions to—the Elm Creek Quilts series throughout the years.

Many thanks to Tara Shaughnessy, nanny extraordinaire, who lovingly cares for my boys and gives me time to write.

I thank Lou Kirby and Susan Robb at the Stagecoach Inn Museum in Newbury Park, California, who generously provided historical details that helped shape two important settings in this novel; Ross E. Pollock of the B&O Railroad Historical Society for advising me regarding rail travel in the 1920s; and Jeanette Berard, special collections librarian at the Thousand Oaks City Library, who directed me to invaluable research sources. I am also indebted to Mary Kay Brown, a fine quilter and storyteller, for sharing her perspective of Southern California farm life, and to the late Patricia A. Allen, whose chronicles of life in the Conejo Valley informed the research for this novel. It was my great privilege to know Pat when we both worked at the Thousand Oaks City Library years ago. Her love for local history inspired my own.

Thank you to the friends and family who have supported and encouraged me through the years, especially Geraldine Neidenbach, Heather Neidenbach, Nic Neidenbach, Virginia Riechman, and Leonard and Marlene Chiaverini. My late grandfather, Edward Riechman, encouraged me until the end.

As always, I thank my husband, Marty, and my sons, Nicholas and Michael, for everything.

1924

A

s her father’s car rumbled across the bridge over Elm Creek and emerged from the forest of bare-limbed trees onto a broad, snow-covered lawn of the Bergstrom estate, Elizabeth Bergstrom was seized by the sudden and unshakable certainty that she should not have come to this place. She should have stayed in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to help her brother run the hotel, even though business invariably slowed during the holiday week. Or she should have offered to help care for her sister’s newborn twins. Even celebrating Christmas alone would have been preferable to returning to Elm Creek Manor. Her lifelong feelings of warmth and comfort toward the family home had suddenly given way to dread and foreboding. She would have to pass the week next door to Henry, knowing that he was near, and waiting in vain for him to come to her.

As Elm Creek Manor came into view, Elizabeth watched her father straighten in the driver’s seat, his leather-gloved fingers flexing around the steering wheel of the new Model T Ford, an unaccustomed look of ease and contentment on his face. He never drank at Elm Creek Manor, nor in the days leading up to their visits, which made Elizabeth wonder why he could not abstain in Harrisburg as well. Apparently he craved his brothers’ approval more than that of his wife and children, not that anyone but Elizabeth ever complained about his drinking.

“We’re almost home,” Elizabeth’s father said. Her mother responded with an almost inaudible sniff. It irked her that after all these years, her husband still referred to Elm Creek Manor as home, rather than their stylish apartment in the hotel her father had turned over to their management upon their marriage. Second only to her father’s flagship hotel, the Riverview Arms was smartly situated on the most fashionable street in Harrisburg, just blocks from the capitol building. It was a good living, much more reliable and lucrative than raising horses for Bergstrom Thoroughbreds. On his better days, George remembered that, but his insistence upon calling Elm Creek Manor home smacked of ingratitude.

But in this matter, if nothing else, Elizabeth understood her father. Of course Elm Creek Manor was home. The first Bergstroms in America had established the farm in 1857 and ever since, their family had run the farm and raised their prizewinning horses there, building on to the original farmhouse as the number of their descendants grew. They had lived, loved, argued, and celebrated within those gray stone walls for generations. But it was her father’s fate to fall in love with a girl who loved the comforts of the city too much to abandon them for life on a horse farm. He could not have Millie and Elm Creek Manor both, so he accepted his future father-in-law’s offer to sell his stake in Bergstrom Thoroughbreds and invest the profits in the Riverview Arms. Still, though he had sold his inheritance to his siblings, Elizabeth’s father would always consider Elm Creek Manor the home of his heart.

And so would she, Elizabeth told herself firmly. Though Elm Creek Manor would never belong to her the way it would her cousins, every visit would be a homecoming for as long as she lived. She would not mourn for what was lost, whether an inheritance sold off before it could pass to her, or the love of a good man whose affection she had taken for granted.

Her father parked in the circular drive and took his wife’s hand to help her from the car. Elizabeth climbed down from the backseat unassisted. A host of aunts, uncles, and cousins greeted them at the door at the top of the veranda. Uncle Fred embraced his younger brother while dear Aunt Eleanor kissed Elizabeth’s mother on both cheeks. Aunt Eleanor’s eyes sparkled with delight to have the family reunited again, but she was paler and thinner than she had been when Elizabeth last saw her, at the end of summer. Aunt Eleanor had heart trouble and had never in Elizabeth’s memory been robust, but she was so spirited that one could almost forget her affliction. Elizabeth wondered if those who lived with her daily were oblivious to how she weakened by imperceptible degrees.

Suddenly Elizabeth’s four-year-old cousin, Sylvia, darted through the crowd of taller relatives and took hold of Elizabeth’s sleeve. “I thought you were never going to get here,” she cried. “Come and play with me.”

“Let me at least get though the doorway,” said Elizabeth, laughing as Sylvia tugged off her coat. She had hoped to linger long enough to ask Aunt Eleanor—casually, of course—if she had any news of the Nelson family, but Sylvia seized her hand and led her across the marble foyer and up two flights of stairs to the nursery before Eleanor could even give her aunt and uncle a proper greeting.

Elizabeth would have to wait until supper to learn no one had seen Henry Nelson since the harvest dance in early November, except to wave to him from a distance as he worked in the fields with his brothers and father. Elizabeth feigned indifference, but her heart sank at the thought of Henry with some other girl on his arm—someone pretty and cheerful who didn’t spend half her time in a far-distant city writing teasing letters about all the fun she was having with other young men. It was probably too much to hope Henry had danced only with his sister.

By the next morning Elizabeth had persuaded herself that she didn’t care how Henry might have carried on at some silly country dance. After all, since they had said good-bye at the end of the summer, she had attended many dances, shows, and clubs, always escorted by one handsome fellow or another. Her mother worried that she was running with a fast crowd, but her father, who should have known better since his own hotel had a nightclub, assumed Elizabeth and her friends passed the time together as his own generation had—in carefully supervised, sedate activities where young men and women congregated on opposite sides of the room unless prompted by a chaperone to interact. Elizabeth’s mother had a more vivid imagination, and it was she who waited up for her youngest daughter with the lights on until she was safely tucked into bed on Friday and Saturday nights.

Every summer, Elizabeth surprised her mother by willingly abandoning the delights of the city for Elm Creek Manor. Millie, oblivious to the appeal of the solace and serenity of the farm, always expected Elizabeth to put up more of an argument. Elizabeth certainly did about everything else. She wanted to bob her hair and wear dresses with hemlines up to her knee. She plastered her bedroom walls with magazine photographs of Paris, London, Venice, and other places she was highly unlikely to visit, covering up the perfectly lovely floral wallpaper selected by Millie’s mother when the hotel was built. She chatted easily with young men, guests of the hotel, before they had been properly introduced. Millie shook her head in despair over her daughter’s seeming indifference to how things looked, to what people thought. Why should anyone believe she was a well-brought-up girl if she didn’t behave like one?

Yet every year as spring turned to summer, Elizabeth found herself longing for the cool breeze off the Four Brothers Mountains, the scent of apple blossoms in the orchard, the grace and speed of the horses, the awkward beauty of the colts, the warmth and affection of her aunts and uncles and grandparents. She felt at ease at Elm Creek Manor. Her meddling mother was far away. She was in no danger of walking into a room to find her father passed out over a ledger, an empty brandy bottle on the desk. There was only comfort and acceptance and peace. And Henry.

Once he had only been Henry Nelson from the next farm over, a boy more her brother’s friend than her own. All the children played together, Bergstroms and Nelsons meeting at the flat rock beneath the willow next to Elm Creek after chores were done and running wild in the forests until they were called home for supper. They met again after evening chores and stayed out well after dark, playing hide-and-seek and Ghost in the Graveyard. One hot August night on the eve of her return to the city, Elizabeth, her brother Lawrence, Henry, and Henry’s brother climbed to the top of a haystack and lay on their backs watching the night sky for shooting stars. One by one the other children crept off home to bed, but Elizabeth felt compelled to stay until she had counted one hundred shooting stars. Secretly, she had convinced herself that if she could stay awake long enough to count one hundred stars, her parents would decide that they could stay another day.

She had only reached fifty-one when Lawrence sat up and brushed hay from his hair. “We should go in.”

“If you want to go in, go ahead. I’ll come when I’m ready.”

“I’m not letting you walk back alone in the dark. You’ll probably trip over a rock and fall in the creek.”

The darkness hid Elizabeth’s scarlet flush of shame and anger. Lawrence never made any effort to disguise his certainty that his youngest sister would fail at everything she tried. “I will not. I know the way as well as you.”

“I’ll walk back with her,” said Henry.

Lawrence agreed, glad to be rid of the burden, then he slid down from the haystack and disappeared into the night.

Elizabeth counted shooting stars in indignant silence.

“Thank you,” she said, after a while. She lay back and gazed up at the starry heavens, hay prickling beneath her, warm and sweet from the sun. After a time, Henry’s hand touched hers, and closed around it. Warmth bloomed inside her, and she knew suddenly that after this summer, everything would be different. Henry had chosen her over her brother. Henry was hers.

She was fourteen.

After that, whenever Henry came to Elm Creek Manor, Elizabeth knew she was the person he had come to see. They began exchanging letters during the months they were separated, letters in which each confided more about their hopes and fears than either would have been able to say aloud. Whenever they reunited after a long absence, Elizabeth always experienced a fleeting moment of shyness, wondering if she should have told him about her dreams to visit Paris and London and Venice, her longing to leave the stifling streets of Harrisburg for the rolling hills and green forests of the Elm Creek Valley, her shame and embarrassment when her father stumbled through the hotel lobby after returning home from his favorite speakeasy, her frustration when the rest of the family turned a blind eye. But Henry never laughed at her or turned away in disgust. In time, he became her dearest confidant and closest friend.

As the years passed, Elizabeth wondered if he would ever become more than that. He never drowned her in flattery the way other young men did; in fact, he was so plainspoken and solemn she often wondered if he cared for her at all. Sometimes she teased him by describing the parties she attended back home, the flowers other young men brought her, the poems they sent. She casually threw out references to the movies she had seen in one fellow’s company or another’s, the dances she enjoyed, how Gerald preferred the fox-trot but Jack was wild about the Charleston and Frank seemed to consider himself another Rudolph Valentino, the way he danced the tango. She hoped to provoke Henry into making romantic gestures of his own, or at least to do something that might indicate a hidden reservoir of jealousy.

In her most recent letter, she had described a Christmas concert she had attended with a young man whose determination to marry her had only increased after she declined his first proposal. She had worn a blue velvet dress with a matching cloche hat; her escort had given her a corsage with three roses and a ribbon the exact shade of her dress. They had traveled in style in his father’s new Packard. The next day, their photo appeared on the society page of the Harrisburg

Patriot

above a caption that declared them the most handsome couple in attendance. Elizabeth included the newspaper clipping in her letter and asked Henry for his opinion: “Do you think this will encourage him to think of us as a couple? I should discourage him, but he’s such a sweet boy I hate to seem unkind. I imagine many girls are eventually won this way. Persistence is admirable in a man. If he doesn’t become impatient waiting for me, maybe someday I will come to think of him as more than a friend.”

Satisfied, she sent off her letter and awaited a declaration of Henry’s true feelings by return mail.

It never came.

As the days passed, she began to worry that instead of stirring him into action, she had driven him away. Henry was, after all, a practical man. He would not pursue a lost cause, and she had all but declared the inevitability of her marriage to another more persistent, more expressive man. Henry had endured her teasing stoically through the years, but to repay him with musings that she might fall in love with someone else might, possibly, have been going too far.

Henry had never said he loved her. He had made her no promises. He had never kissed her and rarely held her hand except to help her jump from stone to stone as they crossed Elm Creek at the narrows, or to assist her onto her horse when they went riding. She had it on very good authority that he had not sat around pining for her at that harvest dance. How dare he end a ten-year friendship and five-year correspondence when she quite reasonably asked his opinion about the man who seemed most interested in marrying her? He ought to be flattered that she thought so highly of his opinion, especially since he seemed to lack any romantic instincts whatsoever. She would have done better to consult Lawrence.