Embers of War (5 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

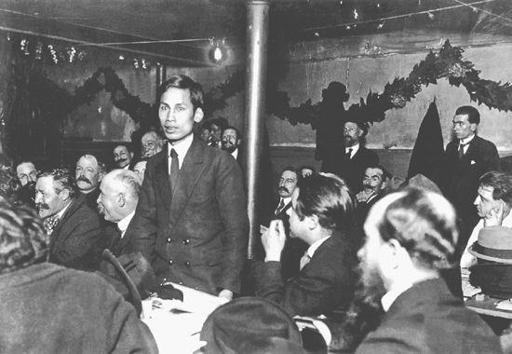

A striking photograph taken at the meeting shows a slender and intense Ho addressing a group of well-fed and mustachioed Frenchmen, appealing to them for support, “in the name of all Socialists, right wing or left wing.”

It is impossible for me in just a few minutes to demonstrate to you all the atrocities committed in Indochina by the bandits of capitalism. There are more prisons than schools and the prisons are always terribly overcrowded.… Freedom of the press and opinion does not exist for us, nor does the freedom to unite or associate. We don’t have the right to emigrate or travel abroad. We live in the blackest ignorance because we don’t have the freedom of instruction. In Indochina, they do their best to intoxicate us with opium and brutalize us with alcohol. They kill many thousands of [Vietnamese] and massacre thousands of others to defend interests that are not theirs. That, comrades, is how twenty million [Vietnamese], who represent more than half the population of France, are treated.

18

The speech, twelve minutes in length and delivered without notes, won warm applause but little more. Ho quickly realized that colonialism ranked low for a party focused on the struggle between capitalism and socialism within France. When a group of socialists broke off to form the French Communist Party, Ho went with them. He had read Lenin’s “Theses on the National and Colonial Questions,” a document that, in his own words, attracted him as a means of liberating Vietnam and other oppressed countries from colonial rule. Other Marxist writers whose work he knew seemed concerned only with how to achieve a classless utopia, a subject that left him cold. Only Lenin spoke powerfully about the connection between capitalism and imperialism and about the potential for nationalist movements in Africa and Asia. Only he offered a cogent explanation for colonialist rule and a viable blueprint for national liberation and for modernizing a poor agricultural society such as Vietnam’s. Communism could be applied to Asia, Ho Chi Minh assured his Vietnamese allies in Paris; more than that, it was in keeping with Asian traditions based on notions of social equality and community. Moreover, Lenin had pledged Soviet support, through the Comintern, for nationalist uprisings throughout the colonial world as a key first step in fomenting worldwide socialist revolution against the capitalist order. What could be more relevant to Indochina’s situation?

19

NGUYEN AI QUOC AT THE CONGRESS OF THE FRENCH SOCIALIST PARTY, TOURS, DECEMBER 29, 1920.

(photo credit prl.1)

“What emotion, enthusiasm, clear-sightedness and confidence it instilled in me,” he recalled, years later, of reading Lenin’s pamphlet. “I was overjoyed to tears. Though sitting alone in my room, I shouted aloud as if addressing large crowds: ‘Dear martyrs, compatriots! This is what we need, this is our path to liberation.’ ”

20

One is tempted to draw a straight line between the failure of the great powers to address the colonial question seriously in 1919 and this decision by Ho Chi Minh—and many other Asian nationalists—to turn to more aggressive means to achieve independent nation-states. There’s something to the notion. Lenin’s position on colonialism and self-determination was substantially formed by the time the peace conference got under way, but he was very much in Wilson’s shadow that year, his words far less influential in the colonial world. The American president had set the terms of the armistice and appeared ready to do the same for the peace settlement. Upon arrival in Europe, he was showered with adulation everywhere he went, greeted as a conquering hero, a savior of the world. Lenin’s Bolsheviks, meanwhile, were struggling to maintain power in Russia, engaged in a bloody civil war whose outcome was anything but certain. Only later, after the collapse of what historian Erez Manela has aptly called “the Wilsonian Moment” and the stabilization of Soviet rule in Russia, did Lenin’s influence in the colonial world begin to surpass Wilson’s. For Ho Chi Minh, the turn had been made by the early weeks of 1921.

21

Thus began for Ho a frenetic period of writing and of attending conferences and lectures. He cofounded a journal,

La Paria

(

The Outcast

), and churned out articles for publications such as

Le Journal du peuple, L’Humanité

, and

La revue communiste

. He wrote and staged a play,

Le Dragon de bambou

, a scathing portrayal of an imaginary Asian king; the audience response was apparently underwhelming, and the play closed after a brief run. He found time to attend art exhibitions and concerts, to read Hugo and Voltaire and Shakespeare, and to hang out in the cafés of Montmartre, where everyone debated everything. In May 1922 he even wrote an article for the movie magazine

Cinégraph

that showed again his complex view of the colonial metropole. The French boxer Georges Carpentier had just defeated the British champion Ted Lewis, and Ho, writing under the pseudonym Guy N’Qua, waxed indignant that French sportswriters had resorted to Franglais in their coverage with phrases such as “le manager,” “le knockout,” “le round.” He urged Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré to ban the use of foreign words by newspapers. France, he grandly proclaimed in a letter written during this period, was the land of Voltaire and Hugo, who personified “the spirit of brotherhood and noble love of peace” that permeated French society.

22

In these years, as he would all his life, Ho made a deep and winning impression on those he encountered. Many remarked on his humor, sensitivity, and sentimentality, on his extraordinary ability to charm. Recalled Léo Poldès, a member of the French Socialist Party who founded the Club de Faubourg, the setting for many debates Ho attended:

It was at one of our weekly meetings that I noticed this thin, almost anemic indigene in the rear. He had a Chaplinesque aura about him—simultaneously sad and comic,

vous savez

. I was instantly struck by his piercing dark eyes. He posed a provocative question; it eludes me now. I encouraged him to return. He did, and I grew more and more affectionate toward him. He was

très sympathique—

reserved but not shy, intense but not fanatical, and extremely clever. I especially liked his ironic way of deprecating everyone while, at the same time, deprecating himself.

23

Later many of these traits would appear also in his public utterances and his diplomatic negotiations, which some interpreted as posturing intended merely to mislead his interlocutors and enemies. Perhaps, but if Ho was always a tactician, the evidence is strong that he also had his spontaneous side. A marvelous example of this comes from Jacques Sternel, a union organizer who offered words of support for Vietnamese workers in France. Ho came up to thank him. “He asked my permission to kiss me on both cheeks,” Sternel remembered. “And it was certainly not an exceptional gesture on his part. There were only three of us there: him, my wife, and I. That’s just the kind of emotional impulses he always had.”

24

IV

THE CHARM AND THE CLEVER DEBATING POINTS WENT ONLY SO

far. Over the course of 1922 and the first part of 1923, Ho Chi Minh came to the depressing realization—and not for the last time—that the French Communist Party attached barely more priority to the colonial question than had the Socialists. For both parties, European issues were what truly mattered. No doubt this recognition played into Ho’s decision in 1923 to leave Paris for Moscow. The move would put him closer to home, and he hoped also to meet Lenin and other Soviet leaders. On June 13, 1923, in an elaborately prepared plan to elude police surveillance, he made his way to Gare du Nord and boarded a train for Berlin, posing as a Chinese businessman. From there he continued to Hamburg, then by boat to Petrograd (later Leningrad, now St. Petersburg), finally reaching Moscow at the start of July.

Here too there would be disappointment. Lenin was ill and dying, and passed away in January 1924. Ho Chi Minh took the news hard: “Lenin was our father, our teacher, our comrade, our representative. Now, he is a shining star showing us the way to Socialism.” Ho joined the crowds waiting hours in –30°C temperatures to view the dead leader, and suffered frostbite to his fingers and nose. He participated in meetings of the Comintern, wrote articles for various publications, and, it seems, enrolled at the newly founded School for the Oppressed People of the East (also known as the Stalin School), which trained Communist cadres and helped organize revolutionary movements in Asia. But Ho found relatively little interest for his message—which he articulated in meetings both of the Comintern and of the Peasant International, or Cresintern—that the agrarian societies of Asia had nationalist aspirations and revolutionary potential that must be nurtured. Eurocentrism reigned supreme here just as it did in the French Communist Party, and just as it did among American champions of “self-determination.” He was, he later said, a “voice crying in the wilderness.”

25

Still, the Moscow interlude must have been a heady time for Ho, as he communed with what he called “the great Socialist family.” No longer did he have to fear that the French police were watching his every move, ready to arrest him and charge him with treason. He was seen in Red Square in the company of senior Soviet leaders Gregory Zinoviev and Kliment Voroshilov and became known as a specialist on colonial affairs and also on Asia. In the autumn of 1924, the Soviets sent him to southern China, ostensibly to act as an interpreter for the Comintern’s advisory mission to Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist government in Canton but in reality to organize the first Marxist revolutionary organization in Indochina. To that end, he published a journal, created the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in 1925, and set up a training institute that attracted students from all over Vietnam. Along with Marxism-Leninism, he taught his own brand of revolutionary ethics: thrift, prudence, respect for learning, modesty, and generosity—virtues that, as biographer William J. Duiker notes, had more to do with Confucian morality than with Leninism.

26

In 1927, when Chiang Kai-shek began to crack down on the Chinese left, the institute was disbanded and Ho, pursued by the police, fled to Hong Kong and from there to Moscow. The Comintern sent him to France and then, at his request, to Thailand, where he spent two years organizing Vietnamese expatriates. Then, early in 1930, Ho Chi Minh presided over the creation of the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hong Kong. Eight months later, in October, on Moscow’s instructions, it was renamed the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP), with responsibility for spurring revolutionary activity throughout French Indochina.

Initially, the ICP was but one of a plethora of entities within the Vietnamese nationalist movement. The more Francophile reformist groups advocated nonviolent reformism and were centered in Cochin China. Most sought to change colonial policy without alienating France and vowed to keep Vietnam firmly within the French Union. Of greater lasting significance, however, were more revolutionary approaches, especially in Annam and Tonkin. In the cities of Hanoi and Hue, and in provincial and district capitals scattered throughout Vietnam, anticolonial elements began to form clandestine political organizations dedicated to the eviction of the French and the restoration of national independence. The Vietnamese Nationalist Party—or VNQDD, the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang—was the most important of these groups, and by 1929 it had some fifteen hundred members, most of them organized into small groups in the Red River Delta in Tonkin. Formed on the model of Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party, the VNQDD saw armed revolution as the lone means of gaining freedom for Vietnam, and in early 1930, it tried to foment a general uprising by Vietnamese serving in the French Army. On February 9, Vietnamese infantrymen massacred their French officers in Yen Bai. The French swiftly crushed the revolt, and the VNQDD’s leaders were executed, were jailed, or fled to China. The party ceased to be a threat to colonial control.

27

Other non-Communist nationalist groups fared no better. Despite the intensity of the Vietnamese national identity, these parties were plagued almost from the beginning with deep factional splits and the absence of a mass base. To be sure, internal divisions were a common feature in anticolonial movements throughout the Third World and had many causes, including personality clashes and disputes over strategy. In some places, such as India and Malaya, leaders overcame the differences and established a broad alliance against the colonial power. Not so in Vietnam. Here the regional and tactical differences proved too deep, or the personality disputes too severe, for nationalist parties to band together. To compound the problem, anti-Communist political parties in Vietnam showed scant interest in forming close ties with the mass of the population. With their urban roots and middle-class concerns, party leaders tended to adopt a nonchalant attitude toward the issues vital to Vietnamese peasants, such as land hunger, government corruption, and high taxes.