England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton (43 page)

Read England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton Online

Authors: Kate Williams

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #Political, #History, #England, #Ireland, #Military & Wars, #Professionals & Academics, #Military & Spies

Nelson had written to Fanny telling her to anticipate them for dinner on Saturday. He expected her to put the servants to work and welcome him and his friends with a sumptuous meal. But Fanny had not received the letter. Unsure of what to do, she had hurried to London with Nelson's father to wait for him. The homecoming hero's party reached Round-wood to find only a few servants in the kitchen, little food, no fires, and

hardly any candles. Nelson flew off the handle, suspecting his wife had left his home cold and empty to humiliate him.

After a dismal and anticlimactic evening, the party set off for London the next morning, narrowly avoiding the worst storm since 1703, in which trees were torn out of the ground, signs flew off shops, and houses collapsed. They arrived in London by early afternoon, and Nelson, Emma, and Sir William took suites at Nerot's Hotel in St. James. Mrs. Cadogan and the others went to a cheaper lodging house nearby. Admirers surrounded the hotel and cheered through the rain to see the hero of the Nile and the Cleopatra who had won his heart and, some said, directed the English fleet. Gossip columnists and reporters skulked at the back doors, recording their every move. After lightning visits from the Duke of Queensberry, Fanny arrived, accompanied by Nelson's father, the seventy-eight-year-old Edmund Nelson. Realizing from the newspapers that Nelson had first been to Roundwood, she was almost paralyzed by nerves. Every print shop she passed was selling images of Emma, and the newspapers were churning out jokes about her Attitudes and the same old story about her meteoric rise to fame. Fanny shrank from meeting the tabloid celebrity. Forty-two and conscious that she was aging, she had lain awake through long, lonely nights seething with hatred for her younger rival. She was painfully aware that she had put herself at a terrible disadvantage by missing the chance to receive Emma on home ground.

The meeting was even worse than Fanny had feared. Emma swept in, overexcited and effusive, her dress outlining the now resplendent swell. Fanny finally saw what everybody had kept from her. Lady Hamilton had succeeded where she had failed. She could hardly retain her composure. Nelson received her politely but, although they had been apart for three years, he refused to retire and see her alone. He could not bear to leave Emma, the woman pregnant with the child he had longed for almost as much as he desired glory. Fanny withdrew into herself and seemed cold, and Emma claimed her eyes were icy, with an "antipathy not to be described." In Sir William's favorite hotel, surrounded by cheering crowds wielding flags, Fanny was faced with the bitter truth: she had lost her husband.

Emma was comforted to see that Nelson's ardor for her never faltered, but she knew she had to press her advantage. Lady Nelson joined the Hamiltons and Nelson for dinner at Nerot's at five o'clock. Emma talked enthusiastically, making sure to attract all the attention, even though she had to let Fanny sit by Nelson's side. He left in the early evening to report

to Lord Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and Fanny followed him in her carriage, tormented that Nelson's commanders had underplayed the affair as a mere crush.

Nelson had hoped that his wife would behave like Sir William, recognizing that their marriage had ended and stepping back to allow the lovers to pursue their mutual adoration. But Fanny, disgusted by Sir William's placid acceptance of the affair, had decided to fight. She was Lady Nelson, Baroness Nelson, and Duchess of Bronte, and she was not about to let her husband go. To the delight of the newspapers, the women began a contest for his heart under an increasingly flimsy mien of polite friendship.

William Beckford offered the Hamiltons use of his mansion, 22 Grosvenor Square, and Nelson and Fanny took an expensive furnished house a comfortable walking distance away at 17 Dover Street. Relations between him and his wife rapidly deteriorated. As Fanny knew, if she had been the mother of his children, he would have treated her with greater respect, and more journalists would have taken her side. Childless, she was in a weak position. Nelson visited Emma daily and praised her endlessly to his wife and to anyone else who called at Dover Street. Fanny was too unhappy to pretend to be sweet and forgiving, and in retaliation Nelson refused to behave as her husband in public. He came to hate the sight of her. He tried to dispel his anger and frustration by walking for hours around London late at night before arriving at Emma's house in Grosvenor Square. The autumn of 1800 was such a strain that he declared the following spring that "sooner than live the unhappy life I did when last I came to England, I would stay abroad forever."

Meanwhile, Emma was winning the media war. There were around fifty daily newspapers in circulation, and Emma, looking ever more resplendent, was the toast of every one. Many newspapers had a print run of over four thousand, and as editions were usually shared (Robert Southey estimated that every paper had five readers), we might make a conservative estimate that over a quarter of a million people read about her antics over their meals. Journalists followed her everywhere. The

Morning Herald

extolled Emma's "singularly expressive face," beautiful teeth, dark eyes, and "immensely thick" hair of the "darkest brown" that "trails to the ground," and decided her "the chief curiosity with which that celebrated antiquarian, Sir William Hamilton, has returned to his native country"

1

The Morning Post

gallantly defended her against the

Herald's

slur that she was forty-nine, declaring that she looked no more than twenty-five. She was

only made more beautiful, according to another, by her mysterious "tawny tinge," a quip alluding to Cleopatra. Comparisons of her with the Egyptian queen appeared almost every day

2

The joke was on the difference between the two women as shown in Shakespeare's play: Cleopatra, exotic, powerful, seductive, and fertile, versus Octavia, Antony's dreary, childless wife (who, like Fanny, also came to him as a widow), able to offer only "a holy, cold, and still conversation." Emma even took to wearing Turkish dress to capitalize on the associations with the exotic East.

The English public was enthralled by Emma's growing figure. The loose muslin fashions of the time made it impossible to hide the truth: the hero of the Nile was about to become a father, at the age of forty-two. Emma was hardly ever mentioned without a pointed comment on her "rosy health" and "plump figure," and typically the term

embonpoint.

In the words of the

Morning Herald,

"Lady Hamilton has been a very fine woman; but she has acquired so much

en bon point

and her figure is so swoln that her features and form have lost almost all their original beauty." As another journalist put it, "Lady Hamilton's countenance is of so rosy and blooming a description that, as Dr Graham would say, she appears so far a perfect

Goddess of Health.

" It was traditional to lay straw outside the homes of women in labor. The

Morning Chronicle

published a story about Lady Hamilton next to a joke about ladies who were often "in the straw" and "laid in sheets." Another noted how her "unfortunate personal extension," was making her less quick and graceful than she had been.

3

Now that Emma was in England, every fine lady was experimenting with her look: either dresses in the Turkish style or white draped gowns, headbands rather than hats, and shawls and anchors "alia Nelson." Those still wearing hoops and corsets gave them up. Emma's pregnancy had led her to adopt the French fashion of the empire-line dress, and she pulled the waistline outrageously high. As Melesina Trench sniped, "Her waist is absolutely between her shoulders." Women across the country were besieging their dressmakers, demanding copies of what was, technically, a maternity dress, all of them tying their dresses under their bosoms.

Hundreds dashed to buy Rehberg's book of her Attitudes to borrow ideas for the classical style of dress. The

Lady's Magazine

noted English women's "enthusiastic partiality for the forms and fashions which were preferred among the ancient Greeks and Romans." They even modeled their footwear on Emma's, buying "slippers in imitation of Etruscan ornaments."

4

The Maltese Cross, pinned to Emma's now expansive bust, inspired particularly wild imitation. Cheap gilt versions of the cross were

sold throughout England, and the very wealthiest ladies had their own made out of diamonds. Even Caroline, Princess of Wales, followed Emma's fashion and wore a white dress with a Maltese Cross brooch to attract the attention of the newspapers. Her estranged husband, the prince, hated everything about the German princess he felt he had been forced to marry in 1795, except for the fashions she copied from Lady Hamilton.

∗

He gave a diamond Maltese Cross to his youngest sister, Amelia, in 1806. Poor Fanny was surrounded by women imitating her showy rival in transparent dresses and heavy jewelry. She was utterly isolated.

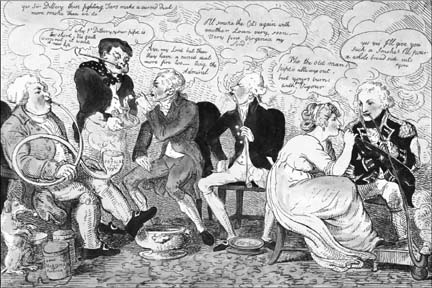

Printing presses worked overtime to produce cartoons, ballads, and bawdy pictures about the affair. The newspapers had suggested before Sir William's marriage to Emma that he was infertile, even impotent, and it seems as if everybody agreed, for nobody assumed that the child she carried was his. On November 18, the windows of the print shops exploded with a new caricature by Isaac Cruikshank,

Smoking Attitudes,

in which Emma, Sir William, Prime Minister Pitt, Nelson, and the lord mayor are smoking pipes, following Nelson's recent attendance at the lord mayor's reception. Smoking was a particularly exotic habit of the upper classes, associated with the East, and the pipes suggest that they are louche and extravagant. Hamilton's pipe is conspicuously unlit, and Emma, dressed in muslin and assuming an Attitude, effuses to Nelson that her husband's "pipe is always out but yours burns with full vigour." Her lover's reply is characteristically blunt: "I'll give you such a smoke I'll pour a whole broad side into you.

†

Every time they opened a newspaper, Sir William's family, friends, and ex-colleagues were shocked to see him represented as a cuckolded, bamboozled, out-of-touch old antiquarian. They were even more scandalized by his sanguine acceptance of the situation. Sir William ignored their complaints, perhaps because he thought them too concerned about whether he would leave his money to Emma. Lady Frances Harpur, Charles Greville's sister, visited Grosvenor Square with every resolution to disapprove, but admitted, "She appears much attached to Sir Wm & He is in much admiration & I believe She constitutes his Happiness." Lady

Frances acknowledged that Emma was treating Sir William kindly, but had to “lament this Idolatory.”

5

William's motives in forgiving the affair were complex. He owed Nelson more than £2,000 for expenses accrued in Naples, Palermo, and the journey home. Unable ever to pay it back, he hinted that Emma was responsible for the expenses by complaining in front of her lover that she gambled too much and would make herself a pauper. He was also genuinely fond of Nelson; furthermore, he knew their friendship gave him social consequence.

∗

The Prince had renounced Mrs. Fitzherbert to marry Caroline, but not his many mistresses or his reputation as a ladies' man.

†

Broadside

was a term for a cheap printed song or pamphlet, as well as a naval term describing the moment when a battleship fired all its guns (from one side) into the enemy. Partly a comment on the outpouring of satiric material the publicity-seeking pair inspired, it was a very rude joke about Nelson's virility.

Isaac Cruikshank's Smoking Attitudes. The Lord Mayor, Sir William, and Prime Minister Pitt enjoy tobacco together. Nelson and Emma are, as ever, utterly absorbed in each other.

Society commentators found Emma's behavior bewildering, although they hardly blinked when a man kept both mistress and wife (such as the setup at Devonshire House, where the duke lived with both his wife and Bess Foster, her friend and his mistress). Sir William excused his wife because he loved her, valued her companionship, and welcomed not having to be her sole support. And, as he knew, his only alternative was being alone. “A man of my age ought not to be attach'd to any worldly thing too much,” he wrote, “but certain it is the greatest attachment I have is the friendship and society of Lrd N. and my dear Emma.” He also felt a little guilty for asking her to sacrifice her desire for children. Because Emma

was happy with Nelson, she was kinder and more solicitous to him than she had been for some time. He always defended his wife and told everyone how much he loved her. He could have sought to harm the relationship by telling Nelson about Emma Carew, but he never disclosed the secret.

The Nelsons and the Hamiltons spent most evenings together at parties, dinners, or theater trips. Fanny sat bolt upright with misery as she watched her husband in ecstasies over Emma's singing and dancing. At his box in Covent Garden, after a musical performance

of The Mouth of the Nile,

Nelson forced his wife to sit on his left, with Emma on his right, so that, as everybody saw, his mistress could help him eat when he wanted to enjoy a snack in the interval. As one newspaper put it, "Lady Hamilton sat on that side of Lord Nelson on which he is disarmed." The

Morning Herald

reported that Emma was "embonpoint" but "extremely pretty" in a blue satin gown and plumed headdress, while Fanny wore a white dress and small white feather.

6