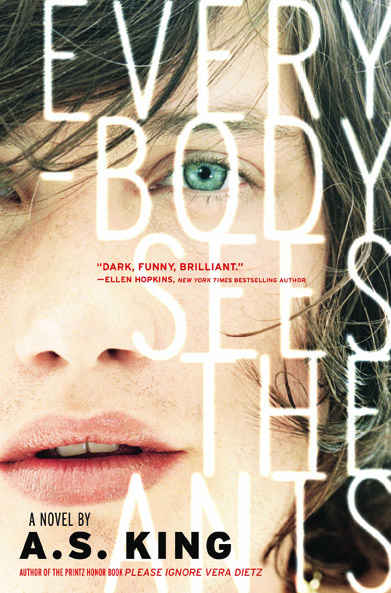

Everybody Sees the Ants

New York Boston

For everybody

who sees the ants

.

Who can stop the tears?

—Robert Nesta Marley

OPERATION DON’T SMILE EVER—FRESHMAN YEAR

All

I did was ask a stupid question.

Six months ago I was assigned the standard second-semester freshman social studies project at Freddy High: Create a survey, evaluate data, graph data, express conclusion in a two-hundred-word paper. This was an easy A. I thought up my question and printed out 120 copies.

The question was:

If you were going to commit suicide, what method would you choose?

This was a common conversation topic between Nader (shotgun in the mouth), Danny (jump in front of a speeding truck) and me (inhaling car fumes), and we’d been joking about it for months during seventh-period study hall. I never saw anything bad in it. That kind of stuff made Nader laugh.

And Nader laughing at my jokes meant maybe I could get through high school with less shrapnel.

When I told the principal that day that it was a joke between Danny, Nader and me, he rolled his eyes and told me that Danny and Nader were not having “social problems” at Freddy High.

“But

you

, Mr. Linderman,

are

.”

Apparently, Evelyn Schwartz went blabbing to the guidance counselor about my questionnaire. She said it was “morbid” and “creepy.” (Evelyn Schwartz has a T-shirt that says

HE DIED FOR ME

with a picture of a dead guy nailed to a cross on it. Oh, the irony.) I really don’t think it’s that morbid of a thing to ask. I’m pretty sure everybody has thought about it at one time or another. My whole plan was to make a few cool pie charts or bar graphs, you know—to show off my Microsoft Excel skills with labels such as

SLIT WRISTS, OVERDOSE

and

FIREARMS

. Anyway, just because a person talks about suicide does not make it a “cry for help.” Even if the kid’s a little bit short or unpopular compared to his so-called friends.

Three hours after my meeting with the principal, I was sitting in the guidance office. Six days later, I was in the conference room with my parents, surrounded by the school district’s “experts” who watched my every move and scribbled notes about my behavior. In the end they recommended family therapy, suggested medications and further professional testing for disorders like depression, ADHD and Asperger’s syndrome. Professional testing! For asking a dumb question about how you’d off yourself if you were going to off yourself.

It’s as if they’d never known one single teenager in their whole lives.

My parents were worse. They just sat there acting as if the “experts” knew me better than they did. The more I watched Mom jiggle her leg and Dad check his watch, the more I realized maybe that was true. Maybe complete strangers

did

know me better than they did.

And seriously—if one more person explained to me how “precious” my life was, I was going to puke. This was Evelyn’s word, straight from her mega-hard-core church group:

Precious

. Precious life.

I said, “Why didn’t anyone think my life was precious when I told them Nader McMillan was pushing me around? That was… what? Second grade? Fifth grade? Seventh grade? Every freaking year of my life?” I didn’t mention the day before in the locker room, but I was thinking about it.

“There’s no need to get hostile, Lucky,” one of them said. “We’re just trying to make sure you’re okay.”

“Do I look okay to you?”

“There’s no need for sarcasm either,” Jerk-off #2 said. “Sometimes it’s hard to grasp just how precious life

is

at your age.”

I laughed. I didn’t know what else to do.

Jerk-off #1 asked me, “Do you think this is funny? Joking about killing yourself?”

And I said yes. Of course, none of us knew then that the suicide questionnaires were going to come back completed. And when they did, I wouldn’t be telling any of these people, that’s for sure. I mean, there they were, asking me if

I

was

okay when they’re letting people like Nader run around and calling him

normal

. Just because he

seems

okay and because he can pin a guy’s shoulders to the mat in under a minute doesn’t mean he’s not cornering kids in the locker room and doing things to them you don’t want to think about. Because he did. I saw him do it and I saw him laughing.

They asked me to wait in the guidance lobby, and I sat in the tweed chair closest to the door, where I could hear them talking to my leg-jiggling, watch-checking parents. Apparently, smiling and joking was an additional sign that I needed “real help.”

And so I initiated Operation Don’t Smile Ever. It’s been a very successful operation. We have perplexed many an enemy.

THE FIRST THING YOU NEED TO KNOW—THE SQUID

My

mother is addicted to swimming. I don’t mean this in a cute, doing-handstands-in-the-shallow-end sort of way. I mean she’s

addicted

—more than two hundred laps a day, no matter what. So I’m spending this summer vacation, like pretty much every summer vacation I can remember, at the Frederickstown Community Swimming Pool. Operation Don’t Smile Ever is still in full effect. I haven’t smiled in six months.

Mom told me once she thinks she’s a reincarnated squid. Maybe she thinks being a squid means she won’t be swallowed by the hole in our family. Maybe being submerged in 250,000 gallons of water all the time makes the hole more comfortable. I heard her yelling at Dad again last night.

“You call this trying?”

“See? Nothing’s ever good enough,” Dad said.

“I dare you to come home and actually see us every damn day in one damn week.”

“I can do that.”

“Starting when?”

After a brief silence he said, “You know, maybe if you weren’t such a nag, I’d want to be around more often.”

The door slammed soon after that, and I was happy he’d left. I don’t like hearing him call her a nag when anyone can see she does what he tells her to do all the time.

Don’t talk to him about that Nader kid, Lori. It’ll just make him embarrassed. And whatever you do, don’t call the principal. That’ll get him beat up worse

.

The Freddy pool isn’t so bad—at least when Nader McMillan isn’t around. Even when he

is

around, working his one or two lifeguarding shifts a week, he’s usually too distracted by his hot lifeguard girlfriend to pay attention to me. So, for the most part, it’s a quiet, friendly neighborhood pool experience.

Mom and I leave home at ten, eat a packed lunch in the shade at one and get back home at six, where there is a 92 percent chance we will eat without Dad and an 8 percent chance he’ll take a break from working at the fancy-schmancy restaurant and come home to eat with us and say things like, “Do you think that berry compote works with the chicken?” Mom says she’s glad Dad’s a chef, because it makes him happy. She only says this to make me feel better about never seeing him. She makes herself feel better by swimming laps.

While Mom worships her pool god, I shoot hoops or play box hockey. I read a book in the shade or play cards with Lara Jones. I eat. The snack bar’s mozzarella sticks are really good as long as Danny Hoffman isn’t working, because Danny is an idiot and he turns the fryer temperature up so the food cooks faster, but the middles of the sticks are still frozen.