Executed at Dawn (13 page)

Authors: David Johnson

Brigadier Crozier (1937), who has received several mentions in this book, claimed to have shot at least one of his own men and ordered his men to machine-gun Portuguese troops who were running away. He justified this by saying, âMen will not, as a rule, risk their lives unnecessarily unless they know that they will be shot down by their own officers if they fail to do so or if they waver.'

â â â

Military police matters came under the office of the adjutant-general and on his behalf, the provost marshal supervised military police duties of the army in the field. The adjutant-general and the provost marshal were represented at every level of the military hierarchy, as defined by Banning (1923):

A general officer, commanding a body of troops abroad, may appoint a Provost-Marshal, who will always be a commissioned officer; his assistants may be officers or non-commissioned officers. His duties are to arrest offenders and he may carry into execution any punishments inflicted by sentence of court martial, but he no longer has any power to inflict punishment on his own authority.

Therefore, each of the British Army divisions on the Western Front had one assistant provost marshal (APM) with the rank of captain or major, together with a number of non-commissioned officers; the APM received his orders from the divisional assistant adjutant-general, and was responsible for organising the police under his command.

â â â

The notes given to Guilford make the following references to the APM and the military police:

Settle day and hour of execution. APM to inform Divisional Headquarters.

Prisoner to be handed over to a guard of his own unit. The NCO in command of the guard to be of full rank and to be specially selected. He will receive instructions from the APM.

He may remain with the prisoner up to the time the latter is prepared for execution (ie when the APM enters the place of confinement and demands the prisoner from the guard).

Military police

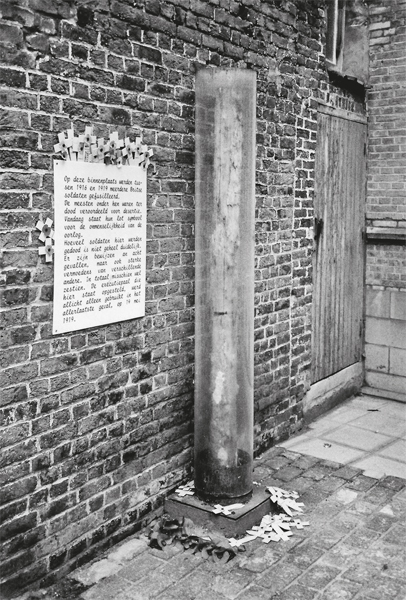

Military Police will be employed to prevent traffic from passing by the place of execution for half an hour before the hour fixed for execution and until all traces of its having taken place have been removed.

The Officer will be present at the promulgation of the sentence to the prisoner and will on that occasion receive from the APM any instructions as necessary.

The APM is responsible for all arrangements and for seeing the sentence carried out.

The APM will collect pay book and identification disc and make them over to the NCO in charge of the guard for delivery at the unit's Orderly Room.

The Medical Officer will provide a three cornered bandage for blindfolding and a small paper disc for fixing over the heart. He will adjust these when requested by the APM.

The firing party will be marched into position by the APM whilst the prisoner is being tied to the post. The APM will so time this that the firing party will be ready for action simultaneously with the completion of the tying up.

The firing party will march in two ranks, halt on the rifles, turn to the right or left, pick up the rifles and come to a ready position, front rank kneeling, rear rank standing. They will press forward safety catch and come to the âpresent' on a signal from the APM. The Officer, when he sees all the men are steady, will give the word âfire'. This is to be the only word of command given after the prisoner leaves the place of confinement.

â â â

The notes issued to Guilford make clear that the medical officer's first action would be to âprovide a three cornered bandage for blindfolding', but this, contrary to public perception, was not done as an act of humanity towards the condemned but rather to save the firing squad from having to look into the man's eyes, because as discussed earlier, that was the weak link in the execution chain.

Sergeant Len Cavinder of the 1/4th East Yorkshire Regiment was present at the execution of Private Charles McColl; Cavinder and another man were detailed to escort McColl from a military prison at Brandhoek to a prison at Ypres (Corns and Hughes-Wilson), the prisoner at that stage being unaware of his fate. It fell to Sergeant Cavinder and his fellow guard to bury Private McColl's body at the conclusion of the execution.

Canon Scott (1922) recalled seeing a man (this was in all probability Private Charles McColl of the 1/4th East Yorkshire Regiment who was executed for desertion on 28 December 1917) prepared for his execution by having a gas mask placed over his head, but back to front so that the eye pieces were at the back. The gas masks were made of flannel and the wearer breathed in through the flannel itself and out through the attached tube â they were unpopular to wear even when under a gas attack. With the helmet on back to front, this would only have added to the horror of the moment for both the condemned man and the firing party.

Who would have decided that this was appropriate, stripping the condemned man of the last vestiges of dignity in his final moments? Canon Scott recalled that it had been the APM who had officiated at this execution and therefore the likelihood is that this would have been his decision because it is unlikely to have been an order passed down the chain of command. If so, it demonstrates that a degree of inhumanity, if not sadism, was present during the last moments of some of those shot.

The notes given to Guilford reveal the central role played by the APM, and the holders of this post were not generally well liked. It is likely that an APM would have been present at more executions than other officers in a division and so would have been looked to for their experience; therefore they wielded considerable influence as to how matters were conducted.

Private James Adamson of the 7th Camerons was executed on 23 November 1917 having been found guilty of cowardice. His execution was recalled in the memoirs of Trooper G.S. Chaplin who was a member of the Mounted Military Police (Putkowski and Sykes, 1996). On the morning of the execution, Chaplin had been sent up the road to stop any traffic, maintaining the army's instructions to avoid bystanders, although it could be argued that allowing those passing to see what was happening would have reinforced the deterrent aspect of the sentence. His memoirs include his assessment of the APM as being âbeneath contempt'.

â â â

Ãtaples was a sprawling base camp in Northern France some 5km from the English Channel. It was an unpopular place with those who found themselves there for training or rehabilitation due to the petty and repressive regime they experienced, imposed by the instructors and the large number of military police. It was here, over six days in September 1917, that a sizeable number of men from the British Army mutinied, thereby threatening the autumn offensive at Passchendaele, much to the consternation of Sir Douglas Haig, the commander-in-chief.

The catalyst for the mutiny was the killing of

â

an inoffensive man by an excited military policeman'

(Brown, 2001). On 9 September 1917, Corporal Gordon Wood, of the 4th Gordon Highlanders, had decided to leave his compound and set off for a visit to the cinema, but on the way he stopped to talk to a girl from the WAAC. Unfortunately for Wood, a military policemen, Private Harry Reeve, came by and saw him lounging around with his tunic buttons undone, talking to the young WAAC. Private Reeve was both a boxing champion and had a reputation as a bully (Allison and Fairley, 1986), and he ordered Corporal Wood to move on, pointing out that he was improperly dressed. The two men argued, whereupon Private Reeve shot and fatally wounded Corporal Wood.

When news of what had occurred spread around the camp, the soldiers erupted in fury and the military police, already the focus of many grievances, had to take flight. They were hunted down and many were badly beaten or killed in the process, despite having been given temporary shelter in local homes. It was an event that led to the brief breakdown of all discipline in the camp.

Allison and Fairley's book, entitled

The Monocled Mutineer

, is a very interesting read, as it describes the story of this not inconsiderable mutiny in detail; there is no need to retell the story here, except to highlight the way that the news of the event and its aftermath were handled.

According to Allison and Fairley, the official records do not mention the scale of the problem, and Sir Douglas Haig went to great lengths to avoid his nemesis David Lloyd George, the prime minister, finding out the true picture, as he feared giving his adversary an excuse to replace him. This was a demonstration of the commander-in-chief living by his mantra that âtruth could be abandoned in the cause of the war effort'. This lack of transparency will be further discussed in the later chapters on abolition and pardons.

Lady Angela Forbes, who was no friend of the commander-in-chief, was much loved by the soldiers, having set up a tea-and-bun hut in the middle of the camp. She was an independent witness of what had gone on at Ãtaples and therefore Sir Douglas Haig ordered that she was to be sent back to Britain. Again, the details of this episode are well set out in

The Monocled Mutineer

and so do not need to be covered here other than to repeat Lady Angela's concern âat the cruel conduct of the military policemen', which she maintained was a reflection of their commander, Assistant Provost Marshal Strachan.

There is also a lack of transparency over what happened to those soldiers who were deemed to be the ringleaders of the mutiny once it had ended. Allison and Fairley state that ten men were eventually shot, and yet the official records only admit to three men in the whole war having been executed for mutiny. To confuse matters further, whilst Corns and Hughes-Wilson list four men who were executed for mutiny, two were killed on 29 October 1916 â which predates the mutiny â with the remaining two being executed in October 1917.

It is possible, therefore, that Labourer Ahmed Mahmoud Mohamed of the Egypt Labour Corps, who was executed on 20 October, and Private Thomas Davis of the 1st Royal Munsters Regiment, who was executed on 4 October, were involved in the events at Ãtaples.

â â â

Military policemen, also known as âredcaps' because of the red band around their caps, could be just as affected by an execution as the next man (Moore, 1999), as shown when one of their number entered a small café in a distressed state and desperate for company. Having found a friendly ear, or at least someone who was prepared to share a table with a military policeman, he told of his experiences the previous night guarding a man who had then been shot that morning. It seemed that just before the condemned man was taken away, he had given his cigarettes and matches, together with a few coins, to the military policeman, saying, âI shan't need these. You'd better have them.'

From the evidence available, the picture that begins to emerge is one where the APM was a central figure regarding the organisation of the executions. The regimental officers, in the absence of regulations governing the conduct of executions, were only too happy to defer to a figure who would have more experience than them in such matters, and this gave rise to the variations that occurred.

The mutiny at Ãtaples resulted from the actions of a military policeman, and Private Reeve appears to be the public face of a regime typified by calculated cruelty on the part of the base's instructors and military police, and indifference to the treatment of the men by the officers who were charged with their care.

Another aspect arising from the mutiny at Ãtaples is the way that the military hierarchy sought to cover up the extent of events there and seem to have manipulated the facts in accordance with Sir Douglas Haig's mantra, mentioned earlier. This will be explored further in a later chapter.

ABOLITION OF THE

DEATH PENALTY IN

THE BRITISH ARMY

The campaign to abolish the death penalty started in 1915 and finally achieved its objective by 1930, having been fought out in the Houses of Parliament and in and around Westminster. The case for abolition was based, by and large, on moral, ethical and logical grounds, but those involved did not seek pardons for those executed. The campaign for pardons got underway in 1989 and ended successfully in 2006, involving and engaging the public much more, although its final battle was again to be fought in the Houses of Parliament and Westminster.

â â â

The final public execution in England took place on 26 May 1868 when Michael Barrett was hung at Newgate for the Fenian bombing at Clerkenwell, yet âpublic' executions were still taking place on the Western Front throughout the First World War because, on occasions, at the apparent whim of their commanding officer, regiments and battalions were paraded to witness the event.

Private Thomas Highgate, as discussed earlier, was executed on 8 September 1914, having been sentenced to death for desertion. Private Highgate served in the 1st Battalion of the Royal West Kents, which was one of the first elements of the British Expeditionary Force to land in France on 15 August 1914 and took part in the fighting at Mons. General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien decided when confirming the sentence to make a very public example of Highgate and ordered that he âshould be killed as publicly as possible'

(Hastings, 2013). As a result, he was executed in front of two companies of his comrades. Smith-Dorrien later justified this by claiming that, as a result, there were no further charges of desertion brought in his division and, therefore, deterrence worked.