Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (38 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

The point being that we have developed scores of euphemisms for the toilet, as well as for bodily functions performed there. And the trend does not merely reflect modern civility. Even in less formally polite medieval times, castles and monasteries had their “necessaries.”

Erasmus of Rotterdam, the sixteenth-century scholar and humanist, who wrote one of history’s early etiquette books, provides us with some of the first recorded rules of behavior for the bathroom and bodily functions. He cautions that “It is impolite to greet someone who is urinating or defecating.” And on breaking wind, he advises the offender to “let a cough hide the explosive sound…. Follow the law: Replace farts with coughs.”

The history of the bathroom itself begins in Scotland ten thousand years ago. Although early man, aware of the toxicity of his own wastes, settled himself near a natural source of moving water, it was the inhabitants of the Orkney Islands off Scotland who built the first latrine-like plumbing systems to carry wastes from the home. A series of crude drains led from stone huts to streams, enabling people to relieve themselves indoors instead of outside.

In the Near East, hygiene was a religious imperative for the ancient Hindus, and as early as 3000

B.C

., many homes had private bathroom facilities. In the Indus River Valley of Pakistan, archaeologists have uncovered private and public baths fitted with terra-cotta pipes encased in brickwork, with taps to control water flow.

The most sophisticated early bathrooms belonged to the royal Minoan families in the palace at Knossos on Crete. By 2000

B.C

., Minoan nobility luxuriated in bathtubs filled and emptied by vertical stone pipes cemented at their joints. Eventually, these were replaced by glazed pottery pipes which slotted together very much like present-day ones. The pipes carried hot and cold water, and linkage drained waste from the royal palace—which also boasted a latrine with an overhead reservoir, which qualifies as history’s first flush toilet. (See “Modern Flush Toilet,” page 203.) The reservoir was designed to trap rainwater, or in its absence, to be hand-filled by buckets of water drawn from a nearby cistern.

Bathroom technology continued among the ancient Egyptians. The homes of Egyptian aristocrats, by 1500

B.C

., were outfitted with copper pipes that carried hot and cold water. And whole-body bathing was an integral part of religious ceremonies. Priests, curiously, were required to immerse themselves in four cold baths a day. The religious aspects of bathing were carried to greater lengths by the Jews under Mosaic law, for whom bodily cleanliness was equated with moral purity. Under the rule of David and Solomon, from about 1000 to 930

B.C

., complex public waterworks were constructed throughout Palestine.

Spas: 2nd Century

B.C

., Rome

It was the Romans, around the second century

B.C

., who turned bathing into a social occasion. They constructed massive public bath complexes which could rival today’s most elaborate and expensive health clubs. With their love of luxury and leisure, the Romans outfitted these social baths with gardens, shops, libraries, exercise rooms, and lounge areas for poetry readings.

The Baths of Caracalla, for example, offered Roman citizens a wide range of health and beauty options. In one immense complex there were body oiling and scraping salons; hot, warm, and cold tub baths; sweating rooms; hair shampooing, scenting, and curling areas; manicure shops; and a gymnasium. A selection of cosmetics and perfumes could also be purchased. After being exercised, washed, and groomed, a Roman patron could read in the adjoining library or stop into a lecture hall for a discussion of philosophy or art. A gallery displayed works of Greek and Roman art, and in another room, still part of the complex, slaves served platters of food and poured wine.

If this sounds like the arrangement in such a celebrity spa as the Golden Door, it was; only the Roman club was considerably larger and catered to

a great many more members—often twenty-five hundred at one time. And that was just the men’s spa. Similar though smaller facilities were often available to women.

Roman spa. Men and women used separate facilities but later mixed bathing became the fashion

.

Though at first men and women bathed separately, mixed bathing later became the fashion. It lasted well into the early Christian era, until the Catholic Church began to dictate state policy. (From written accounts, mixed bathing did not result in the widespread promiscuity that occurred a thousand years later when public baths reemerged in Europe. During this early Renaissance period the Italian word

bagnio

meant both “bath” and “brothel.”)

By

A.D

. 500, Roman bathing spa luxury had ended.

From the decline of the Roman Empire—when invading barbarians destroyed most of the tiled baths and terra-cotta aqueducts—until the later Middle Ages, the bath, and cleanliness in general, was little known or appreciated. The orthodox Christian view in those times maintained that all aspects of the flesh should be mortified as much as possible, and whole-body bathing, which completely exposed the flesh, was regarded as entertaining temptation and thus sinful. That view prevailed throughout most of Europe. A person bathed when he or she was baptized by immersion, and infrequently thereafter. The rich splashed themselves with perfume; the poor stunk.

With the demise of bathing, public and private, went the niceties of indoor bathroom technology in general. The outhouse, outdoor latrines and trenches, and chamber pots reemerged at all levels of society. Christian prudery, compounded by medical superstition concerning the health evils of bathing, all but put an end to sanitation. For hundreds of years, disease was commonplace; epidemics decimated villages and towns.

In Europe, the effects of the 1500s Reformation further exacerbated the disregard for hygiene. Protestants and Catholics, vying to outdo each other in shunning temptations of the flesh, exposed little skin to soap and water throughout a lifetime. Bathroom plumbing, which had been sophisticated two thousand years earlier, was negligible to nonexistent—even in grand European palaces. And publicly performed bodily functions, engaged in whenever and wherever one had the urge, became so commonplace that in 1589 the British royal court was driven to post a public warning in the palace:

Let no one, whoever, he may be, before, at, or after meals, early or late, foul the staircases, corridors, or closets with urine or other filth.

In light of this warning, Erasmus’s 1530 advice— “It is impolite to greet someone who is urinating or defecating” —takes on its full significance.

A hundred years later, etiquette books were still giving the same advice for the same public problem.

The Gallant Ethic, in which it is shown how a young man should commend himself to polite society

, written around 1700, suggests: “If you pass a person who is relieving himself you should act as if you had not seen him.” A French journal of the day provides a glimpse of the extent of the public sanitation problem. “Paris is dreadful. The streets smell so bad that you cannot go out…. The multitude of people in the street produces a stench so detestable that it cannot be endured.”

The sanitation problem was compounded by the chamber pot. With no plumbing in the average home, wastes from the pots were often tossed into the street. Numerous cartoons of the period illustrate the dangers of walking under second-story windows late at night, the preferred time to stealthily empty the pots. This danger, as well as continually fouled gutters, is supposed to have instituted the custom of a gentleman’s escorting a lady on the inside of a walkway, removed from the filth.

Legally, the contents of chamber pots were supposed to be collected early in the morning by “night-soil men.” They transported the refuse in carts to large public cesspools. But not every family could afford to pay, or wait, for the service.

By the 1600s, plumbing technology had reappeared in parts of Europe—but not in the bathroom. The initial construction of the seventeenth-century palace at Versailles—which shortly after its completion would house the French royal family, one thousand noblemen, and four thousand attendants—included no plumbing for toilets or bathrooms, although the system of cascading and gushing outdoor water fountains was grand.

The dawning of the industrial revolution in Britain in the 1700s did nothing to help home or public sanitation. The rapid urbanization and industrialization caused stifling overcrowding and unparalleled squalor. Once-picturesque villages became disease-plagued slums.

It was only after a debilitating outbreak of cholera decimated London in the 1830s that authorities began campaigning for sanitation facilities at

home, in the workplace, and along public streets and in parks. For the remainder of the century, British engineers led the Western world in constructing public and private plumbing firsts. The bathroom, as we take it for granted today, had started to emerge, with its central feature, the modern flush toilet.

Medieval woodcut depicting the danger from a chamber pot being illegally emptied

.

Modern Flush Toilet: 1775, England

That essential convenience of modern living the flush toilet was enjoyed by Minoan royalty four thousand years ago and by few others for the next thirty-five centuries. One version was installed for Queen Elizabeth in 1596, devised by a courtier from Bath who was the queen’s godson, Sir John Harrington. He used the device, which he called “a privy in perfection,” to regain the queen’s favor, for she had banished him from court for circulating racy Italian fiction.

Harrington’s design was quite sophisticated in many respects. It included a high water tower on top of the main housing, a hand-operated tap that permitted water to flow into a tank, and a valve that released sewage into a nearby cesspool.

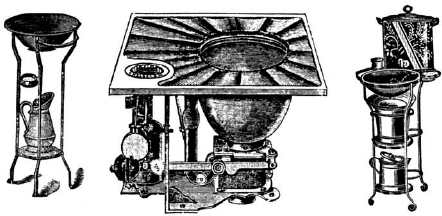

Chamber pots with toilet stands flanking an eighteenth-century flush toilet mechanism

.

Unwisely for Harrington, he wrote a book about the queen’s toilet, titled

The Metamorphosis of Ajax

—Ajax being a pun on the word “jake,” then slang for chamber pot. The book’s earthy humor incensed Elizabeth, who again banished her godson, and his flush toilet became the butt of jokes and fell into disuse.

The next flush device of distinction appeared in 1775, patented by a British mathematician and watchmaker, Alexander Cumming. It differed from Harrington’s design in one significant aspect, which, though small in itself, was revolutionary. Harrington’s toilet (and others that had been devised) connected directly to a cesspool, separated from the pool’s decomposing contents by only a loose trapdoor; the connecting pipe contained no odor-blocking water. Elizabeth herself had criticized the design and complained bitterly that the constant cesspool fumes discouraged her from using her godson’s invention.

In Cumming’s improved design, the soil pipe immediately beneath the bowl curved backward so as, Cumming’s patent application read, “to constantly retain a quantity of water to cut off all communication of smell from below.” He labeled the feature a “stink trap,” and it became an integral part of all future toilet designs.