Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (55 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

A group of peripatetic musicians, Bryant’s Minstrels, carried the song to New Orleans in 1860. They introduced it to the South in their musical

Pocahontas

, based loosely on the relationship between the American Indian princess and Captain John Smith. The song’s immediate success led them to include it in all their shows, and it became the minstrels’ signature number.

Eventually, the term “Dixie” became synonymous with the states below the Mason-Dixon line. When the song’s composer, a staunch Union sympathizer, learned that his tune “Dixie” was played at the inauguration of

Jefferson Davis as president of the Confederate States of America, he said, “If I had known to what use they were going to put my song, I’ll be damned if I’d have written it.” For a number of years, people whistled “Dixie” only in the South.

Abraham Lincoln attempted to change that. On April 10, 1865, the day following Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, President Lincoln delivered a speech outside the White House. He jokingly addressed the South’s monopoly of the song, saying, “I had heard that our adversaries over the way had attempted to appropriate it. I insisted yesterday that we had fairly captured it.” Lincoln then suggested that the entire nation feel free to sing “Dixie,” and he instructed the military band on the White House lawn to strike up the melody to accompany his exit.

West Point Military Academy: 1802, New York

The origin of West Point Military Academy dates back to the Revolutionary War, when the colonists perceived the strategic significance of the Hudson River, particularly of an S-shaped curve along the bank in the region known as West Point.

To control the Hudson was to command a major artery linking New England with the other colonies. General George Washington and his forces gained that control in 1778, occupying the high ground at the S-shaped bend in the river. Washington fortified the town of West Point that year, and in 1779 he established his headquarters there.

During the war, Washington realized that a crash effort to train and outfit civilians every time a conflict arose could never guarantee America’s freedom. The country needed professional soldiers. At the end of the war, in 1783, he argued for the creation of an institution devoted exclusively to the military arts and the science of warfare.

But in the atmosphere of confidence created by victory, no immediate action was taken. Washington came and went as President (1789–1797), as did John Adams (1797–1801). It was President Thomas Jefferson who signed legislation in 1802 establishing the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. With a class of only ten cadets, the academy opened its doors on Independence Day of that year—and none too soon.

War broke out again, faster than anyone had imagined it would. The War of 1812 refocused attention on the country’s desperate need for trained officers. James Madison, then President, upped the size of the Corps of Cadets to 250, and he broadened the curriculum to include general scientific and engineering courses.

The academy was girded for the next conflict, the Civil War of 1861. Tragically, and with poignant irony, the same officers who had trained diligently at West Point to defend America found themselves fighting against each other. During the Civil War, West Point graduates—Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Meade, Lee, Jackson, and Jefferson Davis—dominated both sides

of the conflict. In fact, of the war’s sixty major battles, West Pointers commanded both sides in fifty-five. Though the war was a tragedy for the country as a whole, it was particularly traumatic for the military academy.

In this century, the institution witnessed changes in three principal areas. Following the school’s centennial in 1902, the curriculum was expanded to include English, foreign languages, history, and the social sciences. And following World War II, in recognition of the intense physical demands of modern warfare, the academy focused on physical fitness, with the stated goal to make “Every cadet an athlete.” Perhaps the biggest change in the academy’s history came in 1976, when it admitted females as cadets.

From a Revolutionary War fortress, the site at the

S

-bend in the Hudson became a flourishing center for military and academic excellence—all that General George Washington had intended and more.

Statue of Liberty: 1865, France

The Statue of Liberty, refurbished for her 1986 centennial, is perhaps the most renowned symbol of American patriotism throughout the world. It is the colossal embodiment of an idea that grew out of a dinner conversation between a historian and a sculptor.

In 1865, at a banquet in a town near Versailles, the eminent French jurist and historian Edouard de Laboulaye discussed Franco-American relations with a young sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi. De Laboulaye, an ardent admirer of the United States, had published a three-volume history of the country and was aware of its approaching independence centennial. When the historian suggested that France present America with an impressive gift, sculptor Bartholdi immediately envisioned a massive statue. But at the time, the idea progressed no further than discussion.

A trip later took Bartholdi to Egypt. Strongly influenced by ancient colossi, he attempted to persuade the ruling authorities for a commission to create a large statue to grace the entrance of the newly completed Suez Canal. But before he could secure the assignment, war erupted between France and Prussia, and Bartholdi was summoned to fight.

The idea of a centennial statue for America was never far from the sculptor’s mind. And in 1871, as he sailed into the bustling mouth of New York Harbor on his first visit to the country, his artist’s eyes immediately zeroed in on a site for the work: Bedloe’s Island, a twelve-acre tract lying southwest of the tip of Manhattan. Inspired by this perfect pedestal of an island, Bartholdi completed rough sketches of his colossus before the ship docked. The Franco-American project was undertaken, with the artist, engineers, and fund-raisers aware that the unveiling was a mere five years away.

The statue, to be named “Liberty Enlightening the World,” would be 152 feet high and weigh 225 tons, and its flowing robes were to consist of more than three hundred sheets of hand-hammered copper. France offered to pay for the sculpture; the American public agreed to finance its rock-concrete-and-steel pedestal. To supervise the immense engineering feat, Bartholdi enlisted the skills of French railroad builder Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel, who later would erect the tower that bears his name. And for a fittingly noble, wise, and maternal face for the statue, Bartholdi turned to his mother, who posed for him.

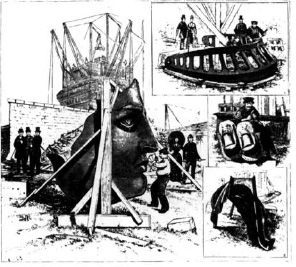

Construction of the Statue of Liberty in 1885

.

From the start, the French contributed generously. Citizens mailed in cash and checks, and the government sponsored a special “Liberty” lottery, with profits going toward construction costs. A total of $400,000 was raised, and the esteemed French composer Charles Gounod created a cantata to celebrate the project.

In America, the public was less enthusiastic. The disinterest centered around one question: Did the country really need—or want—such a monumental gift from France? Publisher Joseph Pulitzer spearheaded a drive for funds in his paper the

World

. In March 1885, Pulitzer editorialized that it would be “an irrevocable disgrace to New York City and the American Republic to have France send us this splendid gift without our having provided so much as a landing place for it.” He lambasted New York’s millionaires for lavishing fortunes on personal luxuries while haggling over the pittances they were asked to contribute to the statue’s pedestal. In two months, Pulitzer’s patriotic editorials and harangues netted a total of $270,000.

The deadline was not met. When the country’s 1876 centennial arrived, only segments of the statue were completed. Thus, as a piecemeal preview, Liberty’s torch arm was displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial celebrations, and two years later, at the Paris Fair, the French were treated to a view of Liberty’s giant head.

Constructing the colossus in France was a herculean challenge, but dismantling

it and shipping it to America seemed an almost insurmountable task. In 1884, the statue’s exterior and interior were taken apart piece by piece and packed into two hundred mammoth wooden crates; the half-million-pound load was hauled by special trucks to a railroad station, where a train of seventy cars transported it to a shipyard. In May 1885, Liberty sailed for America aboard the French warship

Isère

.

When, on October 28, 1886, President Grover Cleveland presided over the statue’s inauguration ceremonies, Lady Liberty did not yet bear her now-immortal poem. The verse “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” was added in 1903, after the statue was closely identified with the great flow of immigrants who landed on nearby Ellis Island.

The moving lines are from a sonnet, “The New Colossus,” composed in 1883 by New York City poet Emma Lazarus. A Sephardic Jew, whose work was praised by the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, Lazarus devoted much of her life to the cause of Jewish nationalism. She tackled the theme of persecution in poems such as “Songs of a Semite,” and in a drama,

The Dance to Death

, based on the accusation leveled against Jews of poisoning water wells and thus causing Europe’s fourteenth-century Black Death.

But her sonnet “The New Colossus” was almost completely ignored by the critics of the day and the public. She had written it for a literary auction held at New York’s Academy of Design, and it expressed her belief in America as a refuge for the oppressed peoples of the world. Sixteen years after her death from cancer in 1887, the sonnet’s final five lines were etched in bronze and in the memory of a nation.

On the Body

Shoes: Pre-2000

B.C

., Near East

Although some clothing originated to shelter the body, most articles of attire, from earliest times, arose as statements of status and social rank. Color, style, and fabric distinguished high priest from layman, lawmaker from lawbreaker, and military leader from his followers. Costume set off a culture’s legends from its legions. In fact, costume is still the most straight-forwardly visible means of stating social hierarchy. As for the contributions made to fashion by the dictates of modesty, they had virtually nothing to do with the origin of clothing and stamped their particular (and often peculiar) imprint on attire centuries later.

Shoes, as we’ll see, though eminently practical, are one early example of clothes as categorizer.

The oldest shoe in existence is a

sandal

. It is constructed of woven papyrus and was discovered in an Egyptian tomb dating from 2000

B.C

. The chief footwear of ancient people in warm climates, sandals exhibited a variety of designs, perhaps as numerous as styles available today.

Greek leather sandals,

krepis

, were variously dyed, decorated, and gilded. The Roman

crepida

had a thicker sole and leather sides, and it laced across the instep. The Gauls preferred the high-backed

campagus

, while a rope sandal of hemp and esparto grass, the

alpargata

, footed the Moors. From tombs, gravesites, and ancient paintings, archaeologists have catalogued hundreds of sandal designs.

Although sandals were the most common ancient footwear, other shoes

were worn. The first recorded nonsandal shoe was a leather wraparound, shaped like a moccasin; it tightened against the foot with rawhide lacing and was a favorite in Babylonia around 1600

B.C

.

A similar snug-fitting leather shoe was worn by upper-class Greek women starting around 600

B.C

., and the stylish colors were white and red. It was the Romans, around 200

B.C

., who first established shoe guilds; the professional shoemakers were the first to fashion footwear specifically for the right and left feet.

Roman footwear, in style and color, clearly designated social class. Women of high station wore closed shoes of white or red, and for special occasions, green or yellow. Women of lower rank wore natural-colored open leather sandals. Senators officially wore brown shoes with four black leather straps wound around the leg up to midcalf, and tied in double knots. Consuls wore white shoes. There were as yet no brand names, but there were certain guild cobblers whose products were sought for their exceptional craftsmanship and comfortable fit. Their shoes were, not surprisingly, more costly.

The word “shoe” changed almost as frequently over the ages as shoe styles. In the English-speaking world, “shoe” evolved through seventeen different spellings, with at least thirty-six variations for the plural. The earliest Anglo-Saxon term was

sceo

, “to cover,” which eventually became in the plural

schewis

, then

shooys

, and finally “shoes.”

Standard Shoe Size

. Until the first decade of the fourteenth century, people in the most civilized European societies, including royalty, could not acquire shoes in standard sizes. And even the most expensive custom-made shoes could vary in size from pair to pair, depending on the measuring and crafting skills of particular cobblers.