Falcon (13 page)

meet as equals in the desert, to swap stories and share food, while their falcons doze in the firelight.

the falcon gentle

We learn that spy

-

hero Richard Hannay’s son is a falconer in John Buchan’s thriller

Island of Sheep.

‘If you keep hawks’, Buchan explains, ‘you have to be a pretty efficient nursemaid, and feed them and wash them and mend for them.’

26

Indeed. Falconry granted the English gentleman a legitimate form of domesticity: when attending to a falcon, one could be both manly

and

a nursemaid. Falcon-training mirrored the educa- tion of the public schoolboy, the purpose of which was to tame and control the natural strength, wildness and unruliness of the growing boy through discipline, physical restraint, self-sac- rifice,

virtu

and honour. And so with the falcon. For centuries, the process of training a falcon has been seen as training oneself, learning patience and bodily and emotional self-control. ‘Training a falcon trains the man quite as much as the man trains the falcon’, explained Harold Webster succinctly in 1964,

27

aBedouin men hawking

on horseback with Saker and Ianner falcons, Palestine, between 1900

and 1920.

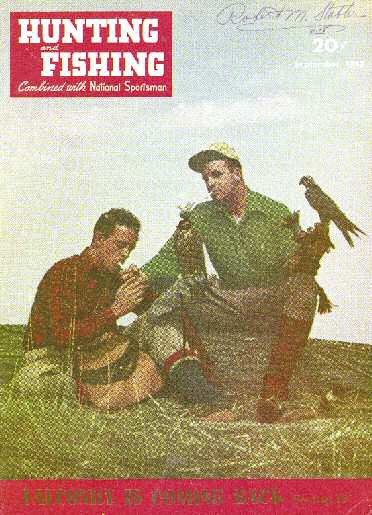

On the left, the novelist John Buchan holds up a kestrel; on the right, his son has a goshawk.

Buchan senior was for some years the presi- dent of the Oxford University Falconry Club.

notion that perhaps informs programmes at several British prisons where inmates keep and breed falcons and hawks.

The notion that the emasculating effects of modern life can be cured by contact with wild nature has been a standard trope in writings on masculinity from Roosevelt to Robert Bly. Associating with wild or ferocious animals – through hunting them or, in the case of falconry, training them – has often been cast as a panacea for such lily-livery. In this tradition, through training a falcon the falconer assumes some of the wildness of the falcon, whilst the falcon correspondingly assumes the man- ners of a man. ‘One never really tames a falcon’, wrote one American falconer in the 1950s. ‘One just becomes a little wild like she is.’

28

Masculine qualities considered lost or marginal- ized in modern life – wildness, power, strength and so on – had already been projected onto falcons. Through the psycholo- gically charged identifications of trainer and hawk during the training process the falconer can repossess these qualities while the falcon at the same time becomes ‘civilized’. No wonder there are still so few female falconers.T. H. White clearly saw magical, almost Freudian transfer- ences between human and hawk as intrinsic to falconry. He described his own attempts as the project of a man ‘alone in a

wood, being tired of most humans in any case, to train a person who was not human, but a bird’.

29

White decided to ‘wake’ his hawk by the old-fashioned method. This involved ‘reciting Shakespeare to keep the hawk awake and thinking with pride and happiness about the hawk’s tradition’:There was a bas-relief of a Babylonian with a hawk on his fist in Khorsabad, which dated from about 3,000 years ago. Many people were not able to understand why this was pleasant, but it was. I thought it was right that I should now be happy to continue as one of a long line. The unconscious of the race was a medium in which one’s own unconscious microscopically swam, and not only in that of the living race but of all the races which had gone before. The Assyrian had begotten children. I grasped that ancestor’s bony hand, in which all the knuckles were as well defined as the nutty calf of his bas-relief leg, across the centuries.

30Many twentieth-century commentators shared White’s desire for historical continuity and community; they also saw falconry as a romantic, pastoralist, anti-modern pursuit. In 1930s America, an era of chivalric youth groups such as the Knights of King Arthur, many boys caught the falconry bug because they were beguiled by falconry’s fantasies of reliving a knightly past. Grown-ups were not immune. Arch-ruralist J. Wentworth Day’s account of a day’s hawking with the British Falconers Club in Kent explained how the hawking expedition was a trip to a lost past:

standing on the hump-backed vallum of a British earth- work, all the sea and the marshes at your feet, the wind in

A 19th-century bas-relief of the Shah of Persia, Nâser al-Din (

d

. 1891).your face, the hawk on your fist, you may know that you are, for a brief space, a heir of the ages. A minor page of history has turned back a thousand years.

31The notion that falconry could be a kind of virtual time-trav- elling is commonplace in inter-war writings on the sport. After the horrors of the Great War, falconry allowed one to reclaim historical continuity; it was a bond, a healing link with a lost pastoral age. Falconers themselves rarely wrote in such purple prose. They tended to keep any lyrical sentiments hidden beneath the bluff demeanour of the practised field-sportsman. But they too were at pains to point out that British falconry had never died out and had an unbroken link with the past.

Fifty years later, the final passages of Stephen Bodio’s book

A Rage for Falcons

seem cast in the same mould. Describing a group of modern American falconers attending to hawk and

‘Shakespeare meets Abercrombie and Fitch’: post-war America reinvents falconry.

quarry in the snow, Bodio muses that ‘there is no way to tell where or when this picture comes from, not on three conti- nents, not in four thousand years’.

32

But falconry is not all history for Bodio. Like many modern falconers, he values fal- conry’s ability to reforge links with nature. ‘Here right at the very edge of the city’, runs the book’s final sentence, ‘it seems we have found a way of going on, of touching the wild in this twen- tieth century.’ His view is analogous to that of Professor Tom Cade, who describes falconry as a form of high-intensity bird- watching. Bodio characterizes falconers as having ‘a feeling for the woods and fields, an intuitive grasp of ecology’.

33

This notion of falconer-as-ecologist was first championed by Aldo Leopold in the 1940s. For him, falconry was superior to mod- ern, technologically augmented hunting methods. It provided insight into the workings of ecological processes, demanded strenuous outdoor activity and required the learning of many practical skills. At heart, it taught the falconer a fortuitous psy- chological ability: to maintain the correct balance between wild and civilized states – in both falcon and falconer. ‘At the slight- est error in the technique of handling’, Leopold wrote, ‘the falconer’s hawk may either “go tame” like

Homo sapiens

or fly away into the blue. All in all falconry is the perfect hobby.’

34the forgotten field sport?

Yet many would disagree with Leopold, seeing falconry less as a means of recapturing right relations with nature, and more as a bloodthirsty, atavistic activity. The rspca lamented the irrevo- cable coarsening of the minds and manners of young ladies who took up the sport in the nineteenth century. A century later, one British anti-hunting group explained that falconers fly their falcons in remote countryside in order to prevent members of

the public seeing what they are doing. I still recall the raised eye- brow and acid response of one falconer to this statement: ‘Do birdwatchers go to remote places so that no one can see them watching birds?’ he enquired.

Falconry’s position within the highly polarized hunting debate is intriguing. Its opponents describe it as the ‘forgotten’ field sport, for it seems aligned with bird-watching rather than hunting in today’s cultural milieu: falconry books, for example, tend to be shelved in the natural-history section of British book- shops rather than in the hunting section. Falconer-biologist Nick Fox enthusiastically promotes falconry as a ‘green’ activity, arguing that the falconer ‘doesn’t need to modify the country- side by building sports grounds or golf courses, or by killing vermin, rearing large numbers of game birds, and restricting public access . . . falconry is a natural, low-impact field-sport,

An anti-falconry engraving from a 19th-century pub- lication by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Note the entirely imaginary dramatic elements here: the live bird on a string and the bow tied around a falcon.

Other books

A Shot of Red by Tracy March

Bodyguard of Lies by Bob Mayer

CLASS ACT (A BRITISH ROCKSTAR BAD BOY ROMANCE) by Julia Gardener

42 by Aaron Rosenberg

The Third Bullet by Stephen Hunter

The Red Hotel (Sissy Sawyer Mysteries) by Masterton, Graham

For His Name's Sake (Psalm 23 Mysteries) by Viguié, Debbie

A Teeny Bit of Trouble by Michael Lee West

Unbreakable Devotion: A New Adult Romance Novel by Chayse, Amanda

Voyage By Dhow by Norman Lewis