Falcon (4 page)

Compared with other birds, a falcon’s digestive system is short, for flesh is easily digested. Falcons cannot digest feathers and fur; these are stored in the crop and ejected from the mouth in the form of a tightly packed ‘casting’ some hours later. They drink infrequently, for most of the moisture they require is derived from their prey and their water economy is impressive; falcon faeces – ‘mutes’ or ‘hawk chalk’ in falconers’ parlance – are composed of faecal matter and a chalky suspension of uric acid crystals. Falcons can excrete uric acid 3,000 times more concentrated than their blood levels. That’s acidic enough to etch steel.

flight

What of flight, the single most celebrated falcon characteristic? Falcon bodies are heavy in relation to their wing area. Their flight profile is unstable and anhedral – that is, ‘^’-shaped, the opposite of the ‘v’-shaped dihedral attitude of soaring vultures and eagles. Their wings have a high aspect-ratio – the ratio between wingspan and wing width – and their low-camber wings are long and pointed. The result is a low-drag conforma- tion more suited to active, flapping flight and fast gliding than soaring. But falcons gain height by powering up on beating wings, or by soaring in rising thermals or updrafts from cliffs or hills. From high perches or from altitudes that may be so high

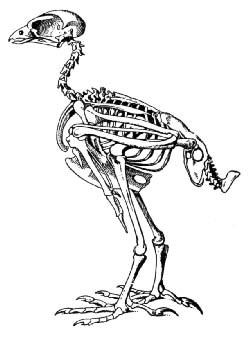

Peregrine falcon skeleton.

Long-distance migrant falcons tend to have narrower, longer wings than those of sedentary populations. Here a dark-phase

s

aker flies through a mountain pass in

n

orthern Pakistan.they are invisible from the ground, falcons stoop, or dive, upon prey. Falcon hunting tactics are to be found codified in fighter pilot tactical manuals of the First and Second World Wars – there are only a few places to hide in the sky. Falcons often attack from above by diving out of the sun; Royal Air Force fighter squadrons would assume positions above enemy aircraft formations in order to do the same. Falcons often use the blind spot of their target to approach unnoticed from behind and beneath and fly their target down. Similarly, raf ‘fighter area tactics’ in the Battle of France called for fighter sections to fly into the blind spot of lone bombers, 2,400 feet behind, 100–200 feet below, before attacking. To approach ground prey falcons glide fast, wings motionless, to present a minimal head- on profile. Sometimes they deceive, imitating the flight style of

harmless birds in order to approach unsuspecting prey. Once overtaken, prey is either grabbed in mid-air or hit hard with one or both feet. At the speeds attained by stooping falcons, this clout often kills the prey outright.

Falcons living in more enclosed habitats have lower aspect- ratio wings and longer tails, a flight conformation suited for rapid turns in a world of obstacles. This is particularly apparent in the New Zealand falcon, which exploits an ecological niche filled elsewhere by hawks. This aberrant falcon follows prey into trees and even stalks prey on foot through undergrowth. Immature falcons also have longer tails and broader wings than adults, a conformation suited to hunting methods amenable to inexperienced birds: young sakers, for example, will ‘quarter’ or hover over rodent-rich grassland. After their first moult, their tails shorten and their wings grow narrower, their feathers stiffer and stronger.

Wing silhouettes of four falcon species. Narrower, longer wings are more suited to aerial attack; broader, rounder wings also allow slow searching flight.

Falcon flight is fast and structurally stressful. Straight-line low-level fast flight in gyrfalcons has been put at 80 mph, but div- ing peregrines reach well over twice this speed. The bony tubercle in falcon nostrils is often presumed to aid breathing at these high speeds, but it may indicate airspeed by sensing temperature or pressure changes produced by different external air-stream velo- cities. An extra pair of bones at the base of the tail gives increased surface area for attaching the powerful depressor muscles of the tail – essential for turning and braking sharply in pursuit flights. Such turns exert phenomenal stresses on the bird. The biometri- cian Vance Tucker attached a miniature accelerometer to trained falcons to record the g-forces experienced when pulling up near vertically from the bottom of steep dives. As blood drains from their eyes and brains, human pilots may experience total loss of consciousness – g-loc – pulling around 6 gs. Eyewitness reports of Tucker’s experiments enthuse about how his accelerometer went ‘off scale’ as the falcons pulled over 25 gs. At this g-loading, a 2 lb falcon weighs over 60 lb.

Vultures and other slow-soaring fliers have rough, loose body feathers and highly emarginated, splayed primary wing feathers that function as miniature aerofoils to permit low air- speeds. Falcon feathers, however, are tightly contoured; they mould the bird into a sleek shape offering little air resistance. Moulted and replaced once a year, they are of several types: long, stiff attenuated

flight

feathers; insulating

down

feathers;

contour

feathers that cover and smooth the body; bristly

crines

around the beak and cere that shed dried blood after a meal; and barely visible long, hairlike

filoplumes

. These are associated with the flight feathers, and are well served at their bases by nerve endings. Their sensory input is thought to monitor the flow of air over the wing surfaces to allow precise adjustments of wing shape in flight.Much of a falcon’s time is taken up with feather-mainte- nance; they preen for long periods and bathe frequently. Gently nibbling the uropygial gland just above the tail, preening falcons pick up a fluid of fatty acids, fat and wax and spread it onto their feathers; in addition to waterproofing them, the fluid contains a vitamin precursor that sunlight converts to vitamin d; this is picked up and ingested in the next preening session. As to plumage colour, black, brown, grey, orange and white are typical falcon tones. Lanners, some saker races and most of the peregrine group have bluish upper parts. This blue colouration is common in bird-killing raptors of other species, but no one knows why this should be the case. A characteristic falcon marking is the dark malar stripe that runs down from beneath the eye. In some species it is so extensive that the falcon appears hooded; in a very few, it may be faint or even absent. The stripe appears to combat glare, functionally akin to the dark make-up American footballers wear beneath their eyes. And the bare skin around their eyes and on their legs and cere varies from pale blue or grey to bright orange. These bright colours may be involved in display and mate choice, for immature falcons are far less brightly coloured on their bare parts. First-year falcons also have streaked rather than barred undersides and are browner or paler than adults. The barred and contrast-rich plumage of adults may be associated with territorial signalling, while dull- coloured juvenile plumage allows young birds to wander relatively unpressed through adult territories in the post-fledging and dis- persal period.

migration

Falcon movements can be epic. Acres of text have been written on the whys and wherefores of bird migration. Recent studies

indicate that a strong genetic component is involved in the development of migratory behaviour in birds, but an external reason is often straightforwardly apparent for falcon migra- tions: food. In Kyrgyzstan, sakers move down from the Tien Shan mountains with the first snowfalls in late summer, follow- ing their prey to the plains below. Rocky Mountain prairie falcons move to higher altitudes in summer because their main prey at lower levels, Townsend’s ground squirrel, hides under- ground to escape the baking heat. Nomadic movements in response to unpredictable food resources are also found in fal- cons living in arid zones, such as lanners. Falcons breeding in the arctic migrate thousands of miles each spring and autumn, ‘leapfrogging’ over resident or partial-migrant birds from mid-latitude populations who live in areas with year-round food. Greenland-nesting peregrines winter as far south as Peru; Siberian peregrines move down to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and as far as South Africa.

Conversely, falcons living in regions where prey is available year-round tend to be sedentary. City peregrines in Manhattan have a year-round source of pigeon food. Peregrines in Britain may use man-made food sources in areas where wild prey is scarce in winter; populations on northern moors have taken advantage of the traditional flight-lines of racing pigeons, much to the dismay of the pigeon-racing community. Peregrines on the humid Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia subsist on seabirds; black shaheens in bird-rich tropical Sri Lanka remain at their breeding territories all year.

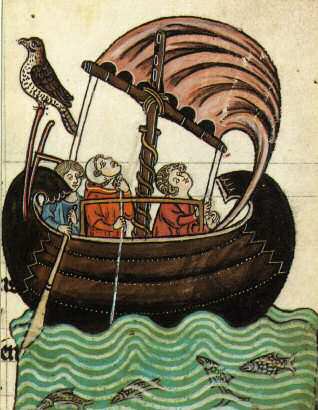

Migranting falcons move fast, sometimes hundreds of miles a day across land or ocean. One of the copies of

De arte venandi cum avibus

, Frederick ii’s thirteenth-century

magnum opus

, has an illustration of a peregrine sitting on the rigging of a ship, and gyrfalcons and peregrines still land on ships during migration.

On a transatlantic crossing in the 1930s the American biologist- falconer Captain Luff Meredith could hardly believe his luck when he was suddenly presented with a beautiful white gyrfalcon: landing on deck mid-crossing, it had been promptly captured by the crew. Meredith’s celebrity falconry status prompted the famous fan dancer Sally Rand to visit him and demand a falcon for her act. Apparently her request was declined.

A falcon resting on a ship, from Frederick ii of Hohenstaufen’s

De arte venandi cum avibus

.

Other books

A Song for Nettie Johnson by Gloria Sawai

Loving Heart (The Broken Heart Series Book 3) by Rose, Angel

Papel moneda by Ken Follett

Policeman's Progress by Bernard Knight

The Filthy Series: The Complete Dark Erotic Serial Novel by Megan D. Martin

A Billionaire Between the Sheets by Katie Lane

The Seven Year Bitch by Jennifer Belle

Attack of the Vampire Weenies by David Lubar

Wyvern by Wen Spencer

Shoot the Piano Player by David Goodis