Falling to Earth (47 page)

Authors: Al Worden

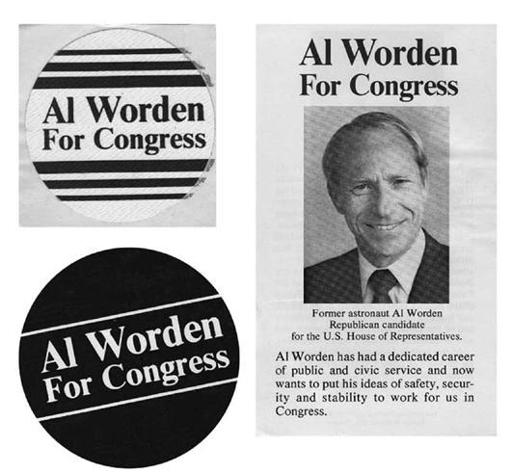

Campaign materials from my run for Congress

I had heard some other Apollo astronauts talk about a sense of peaking after their missions: a feeling that they had done the most significant thing in their lives in their late thirties. What could top flying to the moon? I didn’t feel that way at all.

Going to the moon was wonderful, but in terms of personal achievement, it was a rote skill. It was something I learned how to do, like driving a car or flying an airplane. It didn’t take much intellectual capacity. I needed to memorize facts and know what the machines told me when they gave me information. It didn’t take a lot of creative thought. As a matter of fact, NASA didn’t want creative thought on a moon flight; I needed to focus instead on what was written down, what the structure of the mission was, and if all the systems worked.

I think the most important things we do in life are intellectual, not rote skills. Personally, running for Congress was a much bigger challenge than going to the moon. Where you stand on issues, how you live your life, and how much good you can do in the world are greater challenges than a lunar mission. I hadn’t been successful in my political ambitions, but that didn’t matter. I’d done my best to become a leader through the strength of my intellectual capacity and learned an important lesson. Just like athletes who have success early in life need to have ambitions for when they are no longer at the top of their game, I also needed to not peak early. I decided to find new goals and ambitions.

But first, I needed to take care of some unfinished business.

I had voluntarily turned over my flown postal covers to Chris Kraft during NASA’s investigation on the understanding that I would get them back once it was concluded. I had followed all of the rules when flying my Herrick covers, so I knew they were my personal property. I had never surrendered my ownership of them nor my legal rights to them. Although NASA never told me they believed they owned the covers, they transferred them to the National Archives in August of 1973, along with the covers Dave had carried. The transfer paperwork stated that “these records are historically important and will probably be retained permanently.” To remove them required the signatures of both NASA’s administrator and deputy administrator. I wasn’t informed.

In late 1974 the Justice Department finally informed NASA that no legal action against us was warranted regarding the covers. The investigation ended. The funny thing is that they could never find us guilty of anything. There was a federal statute against using government property for self-gain, but our actions were not enough to warrant its use. Poor judgment was the only charge that NASA could make stick, but that’s not against the law. And yet the covers were not returned to us when we asked for them back. It appeared that NASA wanted us to forget about them.

At that time, I didn’t push the issue. I still felt guilty and penitent. I knew I had screwed up and almost felt that NASA deserved to punish me. But as the years went by, I began to feel I had done my sentence and paid the price. In fact, with hindsight, I felt I had paid a bigger price than my actions deserved. NASA managers had wanted to make an example of me to my fellow astronauts and they had. But in the process, I thought that they had gone overboard to prove their point.

In December of 1978, the Office of the Attorney General quietly issued a memorandum opinion on the Apollo 15 covers and sent it to NASA. Among its conclusions, it stated that NASA had no legal claim to the covers as they were not purchased by public funds nor prepared at public expense. It also found that it was “routine NASA practice” to allow astronauts to carry covers into space. They concluded that Dave’s failure to secure authorization to carry his covers was “inadvertent” and not enough cause for NASA to retain them. NASA’s only claim to my covers, the report suggested, would be if I’d had a commercial arrangement to sell the covers with Herrick. I’d already satisfied investigators that I hadn’t. The memorandum did query whether our crew should ever be able to profit from sales of the covers, but concluded that once we left NASA employment even that stipulation would no longer apply.

The memorandum was not a full exoneration of our actions, nor should it have been. But it blew apart most of the claims NASA had made to keep hold of the covers. Not surprisingly, the memorandum was not widely distributed. I didn’t hear about it myself until October of 1981. When I did, I decided to take some action.

I felt that NASA had washed its hands of the issue by transferring the covers to the National Archives, which just didn’t seem right to me. In fact, it felt like a violation of my constitutional rights. They had taken my personal property and placed it in the archives without following due legal process. I’d been cleared of any illegal acts, but NASA’s actions

did

seem illegal to me. I thought they violated my right of due process under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution, one of my country’s oldest and most venerated laws.

A decade after my spaceflight, I started to talk to lawyers, trying to find one to represent me. Many did not want to touch the case. It was too political, they told me. I would never be able to sue the government and win, even if I were in the right. Perhaps I should find a senator who would fight for me, they suggested. But I didn’t want to drag the case into the political arena. I just wanted what was legally fair and just.

I could understand the lawyers’ apprehension. After all, taking on the government is a big deal. Their reaction did give me second thoughts for a while. But eventually I found an attorney in Palm Beach who would take on the task. It took a lot of explaining to brief him on the intricacies of the events, but luckily I’d kept good documentation. In January of 1982, my attorney officially wrote to NASA and politely but firmly asked for my covers back. I hoped the request would resolve the issue. I really didn’t want to sue NASA. Despite everything, I still loved them.

After a year of fruitless waiting, in February of 1983, we filed a lawsuit in federal court. We requested a jury trial. I was confident that any group of citizens would see the justice in my case.

A number of NASA lawyers contacted me, begging me to drop the case. Couldn’t I see that I had done something wrong all those years ago? Yes, I admitted, I had made a stupid mistake. But two wrongs did not make a right. And I had politely asked for my covers back with no luck, so a lawsuit was my only option.

As the case progressed, I learned that NASA had actually wanted to give the covers back to us based on the advice of the Justice Department, but a number of congressional committees had been against the idea. I learned, too, that the Apollo 16 crew had also turned in their personal covers, and NASA had impounded them. They’d had no luck getting them back either. And an interesting precedent had been set in October 1977 by Ed Mitchell, who had sold one of the covers he took with him to the moon on Apollo 14. According to newspaper reports, some NASA officials were furious, but Ed was a private citizen now, so there was nothing NASA could do. He’d operated under the same lack of rules as our crew.

I was confident about getting my Herrick covers back. Then I discovered that there were even less legal grounds, according to the Justice Department, for NASA to hold the covers that Dave had carried for the three of us. Unlike the covers given to Sieger, they had not been created specifically to sell, only for us to keep. And unlike the Herrick covers, they had never left our possession.

Based on that information, in April 1983 I widened the lawsuit. I contacted Dave and Jim and asked if they wanted me to represent all of us to get those covers back. They agreed. Dave had made his own strong inquiries over the years pressing for the return of the covers and was eager to have them. Jim and Dave did not join me in suing the government, but they helped with the legal fees. If I lost the case, all they would lose was a little money.

NASA didn’t help its case any by beginning to fly postal covers into space itself. The same year I filed my suit, NASA announced plans to carry more than two hundred sixty thousand postal covers on the eighth space shuttle mission in August 1983. They expected to sell them to the public immediately after the flight, make more than one and a half million dollars from the deal, and split the proceeds with the post office. I only learned about it after I’d filed my suit, but I was

very

amused by the coincidence. It made our little handful of covers look like no big deal at all, especially since NASA’s covers were intended for unabashed commercial exploitation.

In May, my lawyers asked NASA for all documents relating to personal items carried on Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo flights and their distribution and current whereabouts. We asked for the dates that each item had been given to a person and where it was now. It sounds like a simple request and was of obvious relevance to my case. In theory, it should have been easy for NASA to comply. But, of course, they’d never kept track of the items astronauts personally carried. They also had very little information about the tens of thousands of items given over the years to public officials. From the president on down, recipients could have sold their gifts long ago, given them away, or passed them on to someone else. In a jury trial, those individuals—including the president—could be called to give important testimony. We planned to depose many of them.

I also asked NASA to produce any and all official orders, directives, and memoranda on PPKs up to and including the time of my flight. If there were rules, I wanted to know what they were. If there were no rules in place, a jury should know that, too.

Given the difficulty that our simple requests would have caused NASA, I wasn’t surprised when the next response was an offer to settle the case.

The settlement agreement between me and the government was finalized on July 15, 1983. They agreed to completely and unconditionally release all the covers to us, at which time my legal counsel would terminate the lawsuit.

As part of the agreement, the three of us on the Apollo 15 crew also agreed not to pursue any further liability against the government in the matter of the covers. It was called an “amicable resolution.” I’d seriously considered saying no to the deal and pursuing a claim for damages against the government for the seizure of my property. I thought I had a strong case and think I would have won a substantial settlement. But, on reflection, that wasn’t the reason I was doing this. I did it to resolve a painful episode in my life and move on.

Dave and Jim had awarded me the power of attorney to pick up their covers. So on July 29, I headed to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., for a morning appointment. The covers were in storage, right next to the Warren Commission report on President Kennedy’s assassination. They were brought to me in a small storage box. In the corner of that mostly empty box was a little pile of postal covers. I placed the box on a table the staff told me had been used as part of the surrender ceremonies at the end of World War II, and I signed my own peace treaty with the government there.

Jim and Dave met me at the archives, and we strolled to a local Irish pub. Over a drink, we divided up the envelopes as agreed. At last, our personal, private property was under our control again, to do with as we wished. It was a peculiar final meeting as a trio, sharing a meal and passing envelopes around. To my recollection, it was the last time the three of us were ever in the same room together.

I had just done Dave and Jim a big favor. Getting the covers back did a lot to clear our names at long last. The newspaper coverage of the settlement used phrases such as “proved themselves right and blameless,” and “after eleven years they’d been vindicated.” Nevertheless, it did not feel like a time to celebrate.

Suing my former employer had been a bitter experience. I didn’t love all of the managers at NASA, but I still loved the work they did, especially now that the space shuttle was flying and the space program was rolling again in a way that it had not done for a decade. Now we’d settled all of our differences. Then, as the people I disliked retired or moved on and the covers issue receded into ancient history, my relationship with NASA grew warm and cozy again. Today, it’s better than ever.

Dave was very pleased with me. And it was oddly satisfying to be the crewmember who took the lead and sorted out the mess. But ten years of reflection on the events surrounding my firing had changed my feelings toward Dave. My deep admiration for him as a spaceflight commander was still strong. My feelings about him as a person were quite different. I didn’t feel particularly friendly to him. And in the quarter of a century that has passed since we sat there having a drink that day, I have rarely felt otherwise.

For better or worse, for richer or poorer, we’ll always be a crew. When I give public presentations, I proudly wear a jacket with an Apollo 15 patch on it; Dave’s and Jim’s names are right there on my chest next to mine. We’ll forever be a team who accomplished an amazing flight. But that is where it ends. I am happy to talk with the public for hours about Dave Scott the outstanding astronaut whom I trusted with my life in space. When it comes to the individual whom I followed just as eagerly here on earth, now that I have written this book, I doubt I will give him much thought for the rest of my life.