Falling to Earth (9 page)

Authors: Al Worden

I didn’t waste any more time sitting around drinking coffee and talking to those guys. I began to wander around the hangar more and more. Just as I had been curious about taking car engines apart and putting them back together as a teenager, I was eager to see what went on with airplane maintenance. I hung around the maintenance crews, talked with them, and grew even more fascinated. There were storage areas for munitions, guided missiles, folding fin rockets, and other amazing things. I wanted to know it all inside out. The guys who worked there, however, told me that they were having problems. They could never get the attention of the officer in charge, as he was always in the lounge with the pilots, relaxing with coffee and cigarettes. They were left to flounder on their own, and as a result the squadron received poor readiness ratings. It was not a good time to be so disorganized, because the air force was adding a special weapons storage facility, which meant we’d be able to have nuclear weapons on-site.

The squadron commander was aware of the problem and noticed my interest. He finally came to me and said he wanted to make some changes, and they involved me. He told me to take over and run the armaments and electronics shop. I had no idea of the scale of the problem when I began, but once I did my weekends were gone. I put in 120-hour weeks sorting out the mess, in addition to being on constant alert as a pilot for three-day shifts. With the help of my senior master sergeant, I put in all my time reorganizing.

The working conditions were deplorable. All the sensitive electronic repairs took place in a lean-to shed that wound around the back of the hangar wall. It was filthy, and despite the sweltering summer heat it had no air-conditioning. So we approached the Convair company, which built our F-102 airplanes, and Hughes, which built many of the weapons systems, and asked a question they had never heard before. We told them that if they would buy the materials, we would rebuild the armament shop. They saw that we were serious and agreed. It took a while, but we put in sound-absorbent ceilings, fluorescent lights, air-conditioning, brand-new workbenches, and a gleaming tiled floor. The place looked like a medical operating theater when we finished. The tools and all the test equipment were where they were supposed to be, and there was no longer any confusion about who did what. The whole operation turned around, and our air force readiness rating jumped from very low to very high.

It turned out that we fixed up that shop just in time. In 1960 we upgraded to the F-106 Delta Dart, dubbed the “ultimate interceptor” airplane. This sleek jet was an advanced version of the F-102 design, with a more powerful engine. It also had an almost completely integrated electronic flight system, with navigation, radio, munitions, and the flight-control systems in big racks. The F-106 was complex and needed the efficient maintenance facility we now had. Because we were so organized, when the air force demonstrated the airplane to senators, congressmen, and others from Washington, they frequently used our facility.

Our second child, Alison Pamela, was born that year. Many fathers would try to be at home and spend more time with two young children. I focused more on my job. I rationalized the decision by saying it was good for my career—and it was. But, to my regret, I missed a lot of my daughters’ precious early years: time that once lost is gone forever.

Luckily, Pam was a wonderful mother, who could fill in for my absence. I don’t remember her ever complaining about me being gone all the time. Perhaps it was my own guilt that I did not spend more time with my family and was not more of a father when my kids were small, but I suspect that a sense of unease crept into our marriage at that moment.

Up until then, despite any hardships, we had made it through on the understanding that we lived the roving military life. I don’t think Pam expected that things would change when we had kids, but I believe she became increasingly wary about what I was doing. When we married, she was a little upset that I chose to join the air force. She didn’t really want me flying, because there is an obvious element of danger to it. I am sure she must have struggled with the fears that all aviators’ wives have, and the pressure to not outwardly show them.

Then I got into the all-weather fighter business, which was not like flying cargo airplanes—it was far more dangerous. Adding to that stress, I was away from home and flying city alerts in the middle of the night. No wonder it was a tense time for her. I was getting more and more into my work, and she had the frustration of covering for me at home because I wasn’t there.

I understand now that Pam needed me to slow down. To reconsider what was most important to me. To invest in my new family. Yet I have to admit that I was oblivious to her worries at the time; I was so caught up in my career. The Air Defense Command came and inspected our maintenance work, and enthusiasm grew about the great job we had done. They particularly appreciated that the contractors, rather than the air force, had paid for most of the rebuilding. Soon I received a phone call summoning me to headquarters. They wanted me to visit all of the other air bases, talk with them about what we had done, and work with them to do the same.

I was grateful for this validation of my work, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. If I had to sit at a desk somewhere, I didn’t want to do it at Air Defense Command Headquarters. I wanted to make a choice that would benefit both me and the air force. So that day I jumped in my car, drove to the Pentagon, and requested that they send me back to college to obtain an advanced degree. At first, the officers I talked to wanted to send me to North Carolina to study nuclear engineering. No, I countered, please send me to the University of Michigan. In fact, I begged and pleaded to be sent to Michigan, to study aerospace engineering. It worked: they enrolled me.

Before we moved back to Michigan, I had my first brush with the space program. The pilots in my squadron all gathered in our coffee room in May of 1961 where we planned to watch the live television reports as NASA attempted to put Alan Shepard in space on America’s first manned flight. Just before his launch, we heard that there was an emergency back at our airfield. Our maintenance officer was trying to land an F-102 fighter, but he couldn’t get the gear down. He would have to land the airplane on its belly. We needed to decide whether to watch the historic spaceflight live, or to take our hot dogs out to the runway and watch the crash. We decided that we could always watch the launch later on, in repeats, but the crash would be unique. So we forgot about the space program for the next few hours, far more pleased to see our maintenance officer return safely to earth than any astronaut. Sorry, Al, it was nothing personal.

We also played a trick on one of the flight commanders in our squadron, an old, crusty pilot who had never been to college. We had someone from the Pentagon make a prank call to inform him that he had been selected for the astronaut program. We kept the joke going for two weeks, and the guy was just walking on air while we congratulated him over and over. When we finally told him the truth, however, I think he was a little relieved, because he knew that he didn’t have the experience needed to be an astronaut. It goes to show that when the manned space program really got going, it meant little to me other than a way to play practical jokes.

I hadn’t distinguished myself academically my first time at the University of Michigan, and in truth I was amazed that they accepted me into graduate school. I quickly discovered how much I needed to catch up; that first summer was unbelievably tough. I took a math course with around a hundred students, and more than eighty of them were high school graduates who knew more math than I’d ever learned. In the years since I had left West Point, the instruction in high school had advanced so much that these kids were way ahead. I broke my back studying to catch up. It took me a year to feel comfortable.

I wanted to go back to Michigan because they had a course specifically for air force officers, with a focus on guided missiles. The course was quite specific to what the air force needed at the time. Ballistic missiles were becoming crucial to our national defense, and rocket airplanes were being built that could reach the edge of space. This was clearly the wave of the future, and I could see that it was better to be ahead of the wave than behind it. Most people in the class went on to work with ballistic missiles, but other pilots like me hoped to go into high-performance flight work. I wanted to learn as much as I could about subjects like control systems, instrumentation, and rocket propulsion. We did a lot of space-related work, which was important for both ballistic missiles and manned spaceflight careers. We also studied a great deal about trajectory analysis, orbital mechanics, and rocket propulsion. I didn’t plan to become an astronaut, but nevertheless I learned much of what I’d need for the job.

I also thought about my air force career beyond being a pilot. Any good air force officer doesn’t obsess about flying. The air force is a management organization, and I looked forward to steady progression through the ranks. At some point that would mean I’d have to leave much of the flying to those under me, and I wanted to learn the necessary management skills.

Once in Michigan, we rented a house only thirty miles from my parents’ home, which was great. Although I’d been happy to leave, I had still missed my family and it was good to be close again. For Pam and the girls, however, it was the same sad story. On the whole, going back to college was a huge mistake. I was busier than ever, and it meant even less time with my growing family. When one parent is away all the time, the other parent has a tough job. If that parent doesn’t complain, nothing changes. If the parent does complain, however subtly, the children will pick up on that feeling. The only way to ease that tension would have been for me to cut back on a career that was advancing rapidly, and I didn’t want to do it.

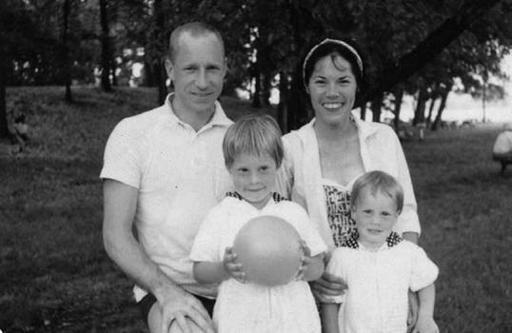

With Pam and our daughters Merrill (left) and Alison, in Michigan in 1962

I had so little home life because I was not just studying: I was also the air force operations officer for all of the other pilots at the college. In my two and a half years there, I had to give around thirty students their check rides, instrument training, and schedule their flying time. Add to those responsibilities studying for master of science degrees in aeronautical, astronautical, and instrumentation engineering, and it is little wonder that I was so preoccupied.

Meanwhile, I looked ahead. I discussed my next move with two other pilots studying at the college. Jay Hanks was the head of academics at the test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base in California, and Bob Buchanan was the deputy commandant. I spent a lot of time with the two of them, and the more I learned about their work, the more I realized that test pilot school was a natural career path for me. It was the top of the ladder for all active aviators. I’d have a chance to further understand the airplanes already in use in the air force, while testing aircraft not yet in service. This experience would put me ahead of the curve, and position me for even higher-ranked air force positions.

My hard work in Michigan paid off academically, and by 1963 I was all set to graduate from college. Bob and Jay had both strongly encouraged me to apply for the next test pilot school class. So I did, and hoped that such highly placed backers would ensure I’d soon be in California, testing the newest and hottest jet fighters. Yet a couple of months later I read an announcement listing the class members starting at Edwards that year. My name was not on it. I could have been upset, but instead I remained philosophical. Forget about it, I told myself, you just didn’t make the cut.

About a week later, the secretary of the air force called me. Had I seen the list of people selected for Edwards, he asked, and had I noticed I was not on it? Yes, I replied, wondering where this call was going. To my surprise, he told me the air force had deliberately taken my name off the list. They had an exchange program with the Royal Air Force over in England and had decided to send me there instead. The exchange program had never been a great success because the American pilots had been unable to meet the academic standards the British required. My superiors had looked at my records, seen that I had a solid academic background, and thought I’d be a perfect fit. It sounded like a great opportunity.

I had a six-month wait before the assignment in England began. Talking it over with some air force advisors, they thought that it would be helpful for me to go through an instrument pilot instruction course while I waited. Flying in England would mean bad weather. Plus the British did not use radar; they relied on directional radio beams to pinpoint aircraft positions. I would have little help when judging my position in the sky. So at Randolph Air Force Base, close to San Antonio, Texas, I spent a few months practicing flight using only instruments. After a couple of years living in one place, my family was leading a nomadic life once again.

Before we left for England, I heard that NASA was accepting applications from jet pilots to become astronauts. It sounded like a good way to enhance my career, so I sent in my paperwork. I figured that I had nothing to lose. While I still wasn’t a test pilot, I had accumulated a lot of flying time and some good reports from my superiors. The answer I received back said, essentially, that timing was not in my favor. They wanted to talk to me, but I was going on an exchange program and they couldn’t interfere with my orders. I figured I would be in England for at least three years, and older than NASA’s age requirements by the time I returned. So, forget it, I thought: it just wasn’t in the cards for me to become an astronaut.