Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors (46 page)

Read Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors Online

Authors: Ann Rule

Tags: #True Crime, #Nook, #Retai, #Fiction

Lawry had been a public defender for sixteen years.

As the trial began, it was unlikely that Tim Diener would be able to testify. He was in the final stages of liver cancer. His testimony had been videotaped, and that would have to serve.

In her opening statement, Carla Carlstrom asked the jurors to correct the mistake that sheriff’s detectives had made in 1975. She submitted that they had had tunnel vision “within days” after Dina Peterson was murdered in her own yard.

“Because of that,” Carlstrom said, “they focused on the wrong person, and her killer went unpunished for

thirty-four years

!”

Moreover, she offered, the original investigators had soon turned to the “Ted Bundy murders” and “disregarded” many factors in the “vicious and angry” attack that could be linked to Jim Groth.

Defense attorney Julie Lawry pointed out in her opening statement that there was no new evidence that might clear Tim Diener of the crime. “In this country, we don’t ‘guess’ people guilty.” She explained that the case against Groth was based “on a whole lot of rumor and speculation.

“Ms. Carlstrom doesn’t know who killed Dina Peterson. Jim Groth doesn’t know who killed Dina Peterson. At the end of this trial, you still won’t know who killed Dina Peterson.”

Jim Groth’s trial took three weeks. Detectives, Dina’s family, and witnesses testified. The defendant declined to testify. Tim Diener’s testimony on videotape was needed as the whole case played out in the trial. He was far too ill to appear in person.

On June 2, 2009, the jury in Judge Inveen’s courtroom returned with a verdict. They found James E. Groth guilty of Dina Peterson’s murder, although they agreed on the lesser charge of second-degree murder.

Sentencing was set for July 24.

Tim Diener died of liver cancer on June 19, 2009. He was fifty-three. For most of his life, he had been a suspect in the murder of the girl he loved. He lived only seventeen months after he was relieved of that dark shadow when Jim Groth was arrested.

Although Jim Groth didn’t take the witness stand in his own defense, he did grant a jail interview to Jennifer Sullivan. He told her that he didn’t kill Dina. When asked who had committed that murder, he said he wasn’t sure.

“My life is over in a sense,” Groth said. “How did these people—knowing what they know—make this determination?”

Lawry said that she had never been so upset by a verdict in her sixteen years in the public defenders’ office. “The evidence is so thin. There’s no DNA—there’s no forensic evidence. There’s no confession. There’s no eyewitnesses . . .”

Circumstantial evidence demands a criteria of what a reasonable man would deem a reasonable outcome when he knows the facts of the case.

Jim Groth was fixated sexually on Dina Peterson. She was seriously dating another suitor. She may have been in her backyard, headed to Tim Diener’s house, when another figure approached her in the dark. Perhaps that person—Jim Groth—was so frustrated that he grabbed her and attempted to kiss, fondle, or rape her. Her natural instinct would have been to fight back, scratching him.

And a reasonable man might well conclude that he had stabbed her with the knife that belonged to the teenager that Dina really cared for.

But Dina was found with her face toward the sky. Someone undoubtedly came back and turned her over. There is little question that that was Jim Groth. As he sat smoking on the beach, he must have begun to wonder if she might still be alive. If she was, Dina would tell on him and he would be in big trouble. And so, I believe, he went back to reassure himself that she was truly dead—and that he would not be identified as the one who stabbed her.

Jim Groth lied, and his two versions of what happened on Valentine’s night were bizarre. He went on to live a life marked by violence to the women in his life.

On July 24, 2009, judge Laura Inveen sentenced Jim Groth to a minimum of sixteen years in prison. His final sentence would go to the Washington State’s Indeterminate Sentencing Review Board, which could sentence him to life in prison.

At Groth’s sentencing, George Peterson spoke as tears ran down his face. Jim Groth stared straight ahead, his face blank of expression.

“Thirty-four years doesn’t heal,” Dina’s father said. “There is a scar on my heart with the loss of my daughter. I have forgiven you, Jim Groth.”

Julie Lawry announced her plans to appeal his sentence. Thus far, that has not been granted.

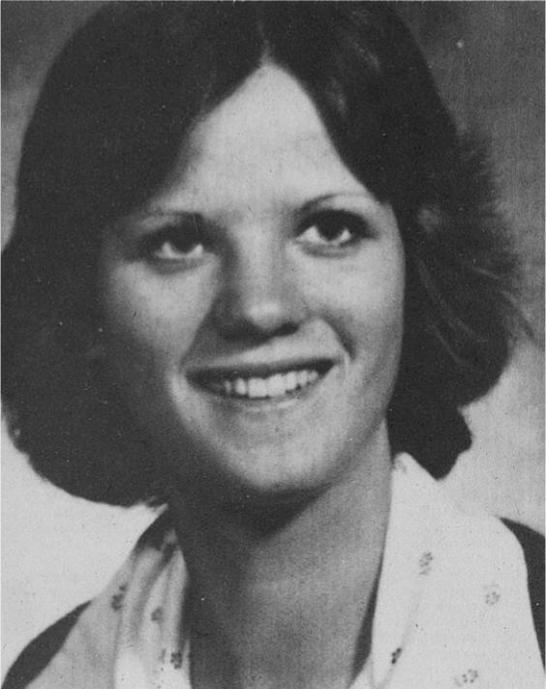

THE LAST VALENTINE’S DAY

Dina Peterson walked to a pizza parlor with a girlfriend, went in her front door, and exited out the back. Relatives heard a “scuffle” in the backyard but believed it was Dina with a friend. They never saw her alive again. It would take more than three decades to find Dina’s killer. (

Police file

)

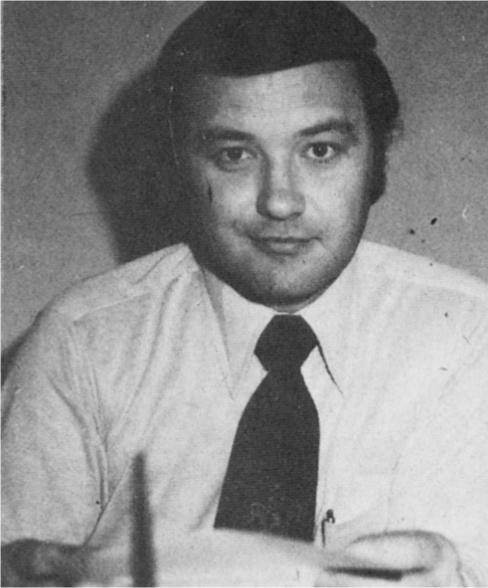

King County sheriff’s lieutenant Richard Kraske, who directed the investigation into Dina Peterson’s murder. (

Ann Rule

)

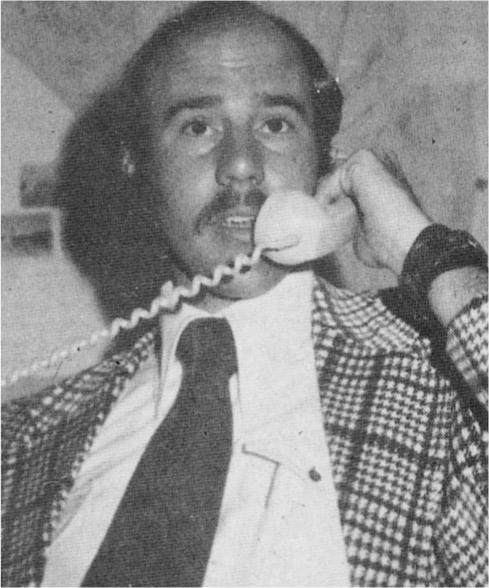

King County sheriff’s detective Randy Hergesheimer worked tirelessly to find Dina’s killer. Sadly, he did not live to see the murderer arrested and convicted. (

Ann Rule

)

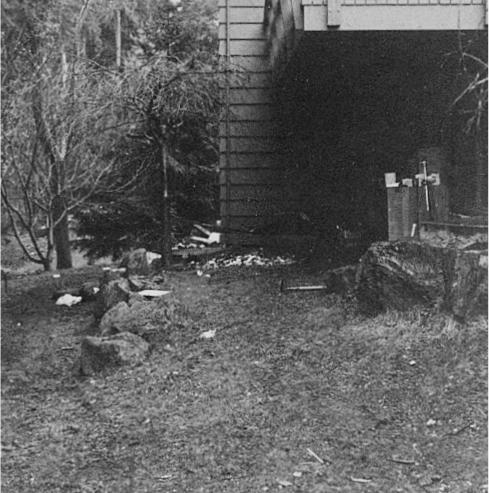

Dina’s body was found in her own backyard—only a few feet from her home. Her little dog had stayed with her all through the chilly night. (

Police file

)

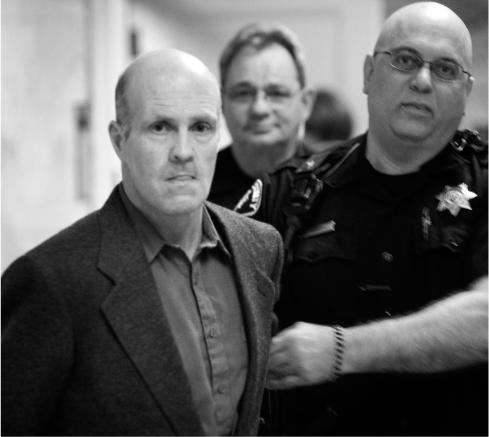

This man had a huge crush on Dina Peterson when they were both teenagers. For years, investigators focused on Dina’s boyfriend—not this man. But the convicted murderer wanted her so badly that he stabbed her to death. With someone else’s knife.

(The Seattle Times)

THE MAN WHO

LOVED TOO MUCH

It was Halloween night in 1977, a holiday for all things ghostlike, macabre, and frightening, and the streets of Seattle were shrouded with appropriate fog and mist. The mournful wail of the foghorns near Puget Sound added to the bleak atmosphere of the night. Lights on the ferries steaming toward the docks on Seattle’s waterfront were only dim beacons. Trick-or-treaters were long since off the streets and home counting their largesse. As the rain began to fall in earnest, it was a time to be home, and anyone with a place to go had headed there.

The only traffic on that Monday night consisted of emergency vehicles. The Seattle Police Department’s blue and white patrol cars crept along in the fog, and an occasional Medic One unit screeched by on an urgent run.

At the downtown police headquarters, the 911 lines had been busy with both critical and crank calls. Operators, used to frantic calls, answered in deceptively laconic voices, fielded the calls, got as much information as they could, and dispatched the cars on the street to addresses all over the city.

The call from the manager at the Rendezvous Restaurant was fairly routine. Their female bartender hadn’t shown up for work that day—nor had she come in to supervise the Halloween party that she’d planned. Her fellow employees were concerned because it wasn’t like Sue Ann Elizabeth Baker to let them down. They had tried to call her repeatedly, only to get a busy signal. They’d checked with an operator at the phone company and learned that Sue Ann’s phone was off the hook.

The 911 operator asked a few questions and then told the manager that she would send a car to Baker’s apartment on Magnolia Bluff.

Police radio communications are, of necessity, terse and to the point. The call that went out shortly after nine that Halloween night didn’t sound particularly ominous.

“Three-Queen-One, copy on a call.”

“Three-Queen-One by, go ahead.”

“Three-Queen-One, service call. Check on the welfare of a Sue Baker, 3459 23 West. No apartment number given. Possibly husband’s name ‘Ron Baker’ is on the mailbox. The phone is off the hook now and someone called her in sick today for work.”

“Received.”

“Subject is a white female about twenty-eight.”

“Received.”

The 911 operator returned to taking other calls. Within a few minutes, the patrolman in Three-Queen-One—Tim Dillon—was calling back in.

“911—Operator 70.”

“Yeah. This is Three-Queen-One on a call to check the welfare of—”

“Uh-huh.”

“I have a dead body. Get me a sergeant. Get me Homicide.”

“Okay, okay. Will do.”

The wheels of a murder investigation were in motion. Homicide detective sergeant Craig VandePutte’s crew was working its last night shift. All the homicide crews worked the night shift every three months. On November 1, they were due to report for the day shift at 7:45

A.M.

But now they had a full night’s work ahead of them. VandePutte and detectives Ted Fonis and Gary Fowler left for the scene with the homicide van. The streets were wet and it was 46 degrees out as they headed north to the upper-middle-class residential district of Magnolia Bluff, one of Seattle’s lowest crime areas.

Patrol Officer Dillon met them outside the cedar-sided apartment house and explained what he had discovered. He’d quickly determined that the apartment where Sue Baker lived was on an upper level, reachable by stairs and then along a catwalk/porch. He’d knocked, and then knocked louder, but there was no response from the darkened apartment.