Fearless (45 page)

“Anyway! To be honest,” Brillstein said, taking one of the champagne glasses and waiting for Max to pop the cork and pour. “I had taken the one point seven million for you and the two hundred for Mrs. Fransisca and the two point three for Nan from Parker this morning despite the fact that I thought they were too low. I did it because of you.” Brillstein stared hard at Max and pursed his lips in a childish attitude of challenge.

Max popped the cork. He quickly poured the frothing liquid into the lawyer’s glass. It reminded him of the hokey chemical drinks in horror movies—Dr. Jekyll’s potion.

“I was about to blow your case,” Max said. He filled a glass for Debby and handed it to her.

“No…” Debby protested. She had another strawberry between her lips. Chocolate was smeared on them. She looked beautiful.

Brillstein was generous. He waved his glass expansively and explained to Debby, “Let’s just say I didn’t want the other side getting their hands on Max the way he was talking. So, one point seven is very good. And I got Nan two point three million, which was okay.”

“And Carla?”

“Even there I thought I’d done great. Two hundred thousand.”

“Two hundred thousand!” Debby choked slightly on the champagne. “That’s nothing. She lost a baby,” Debby insisted in a wounded tone.

Max smiled proudly at his wife and took another strawberry. The champagne was delicious.

“A baby has no earnings you can establish. I was going to argue that the Fransisca baby had a potential career as a child model but they would have shot me down. Really the compensation was for the mother’s pain and suffering and because of the negligence of the seat belt. Although she hadn’t bought him a ticket and he wasn’t entitled to the defective seat—” Brillstein waved at all that with his glass. “It’s craziness. You don’t want to know! It doesn’t matter! Listen to me!” He put his glass down on the table and spread his hands to show the scene. “I go to Gloucester House and meet Parker’s superior, Jameson. I’m not feeling like such a genius, to tell you the truth, so I don’t brag or mention the deal I had just made with Parker. Jameson doesn’t either and I figure that’s class, that’s a real WASP. His people and I have made a deal for over four million dollars that he has final approval of and we don’t even mention it. We order. Then he looks at me and says, ‘I hear your client, Mr. Klein, nearly killed himself and that Fransisca woman.’ I had a piece of bread in my mouth so I nod. Don’t want to spit crumbs all over him. He goes on, very haughty, almost angry. ‘I want to settle your three cases at this lunch. Parker’s dragging his feet. I want to get this done.’ Now I almost choke on the bread because I realize Parker hasn’t told him what we’ve

tentatively

,” Brillstein, grinning, raised a finger in the air, “tentatively because it still wasn’t definite until Parker cleared it with Jameson—”

Max took another strawberry. His throat was dry from the champagne. “We get it!” he croaked at Brillstein. “What happened!”

“So I swallow all the bread,” Brillstein’s face widened into a grin, “and I say, ‘What’s your best offer? I’m happy to hear any number and discuss it.’ So he frowns—he looked incredibly pissed off—and he says, ‘I won’t pay more than four hundred thousand for the baby.’ ” Brillstein giggled.

Max tried to breathe through his nose. The champagne must have stuffed it. He swallowed the rest of his strawberry and looked around for a tissue.

Brillstein seemed disappointed in the response of his audience. “Isn’t that incredible? That was double what Parker had offered. So you know what I say? And this, I have to admit, was a stroke of genius on my part—I say, ‘I can’t take less than five hundred thousand to settle it at this lunch.’ ”

Debby frowned. “But you’d already agreed to—”

Brillstein almost jumped in his desire to cut her off. “Doesn’t matter! Once he offered more it was all off the table. He’s the one with the real authority to deal.”

“Of course,” Max tried to say, but there was little air to say it. His throat thickened. He sat down.

Brillstein moved to a chair opposite him and tapped him on the knee. “So Jameson looks furious, just furious, and he says, ‘Okay. Don’t want to quibble. That’s done.’ ” Brillstein spread his arms wide. “And here I made another great move. I took out my notepad and I wrote down Carla’s name and put the figure next to it and I had him look at it to see that I’ve got it right. Now it’s as good as a done deal and he can’t back out. Then he says, ‘As to the two architects I won’t go above a total package of eight million.’ ” Brillstein clapped his hands together and let his head go back to laugh at the heavens with triumph.

Max struggled to breathe. He sucked from his stomach but nothing could get in through his mouth. His throat had filled in; his nose was sealed. He looked at the box of strawberries and was scared.

When Brillstein brought his head back from his roar of victory, there were tears in his eyes. “We settled on you getting three point five million and Nan gets four point five.” Brillstein shook his head from side to side. “He’s finding out right now. He’s in his huge fucking corner office with his Harvard degree and he’s finding out that the Gloucester House lunch cost him four and a half million dollars!” Brillstein collapsed into guttural laughs.

Max’s forehead broke out into a sweat. He put his head between his knees. He saw his right hand turn blotchy red. His eyes swelled and ached. There was no way to breathe. He stared at the sanded narrow oak floor, the floors that had carried him from childhood until now, through all the duty and grief and joy of life, and he realized those same sanded boards would soon be his deathbed.

He fell.

The ceiling was flashing yellow. A terrible pain was in his ears.

He heard Brillstein shout—“Where the fuck is it! It’s in my fucking bag!”

Max tried to kick his legs but he couldn’t—they were fat columns—dead lumps.

Debby appeared. She was flushed. “Take it easy, Max,” she said.

“I don’t know where to do it!” Brillstein was shouting. “My wife knows!”

Debby’s face covered the flashing ceiling. She pulled at something. “You’re going to be all right, Max,” she said and then he saw her come at his heart with a needle. He tried to scream at her not to kill him but he couldn’t make any sound.

She injected him in the upper arm. She cradled the nape of his neck with her hand and tilted his head back. His suffocating mouth opened to her. She covered it with hers. He felt her hot breath enter his throat. The blockage was dissolved. She leaned back and smiled down at him. His nose suddenly cleared. The ceiling settled.

“You’re fine, Max,” Debby said. “Let the Adrenalin work.”

Max rested on the oak floor and breathed easily. I’m alive, he thought. His throat eased and accepted a gulp of air.

I’m alive, he rejoiced. I’m alive. And I’m afraid.

A BIOGRAPHY OF RAFAEL YGLESIAS

Rafael Yglesias (b. 1954) is a master American storyteller whose career began with the publication of his first novel at seventeen. Through four decades of writing, Yglesias has produced numerous highly acclaimed novels and screenplays, and his fiction is distinguished by its clear-eyed realism and keen insight into human behavior. His books range in style and scope from novels of ideas, psychological thrillers, and biting satires, to self-portraits and portraits of New York society.

Yglesias was born and raised in Washington Heights, a working-class neighborhood in northern Manhattan. Both his parents were writers. His father, Jose, was the son of Cuban and Spanish parents and wrote articles for the

New Yorker

, the

New York Times

, and the

Daily Worker

, as well as novels. His mother, Helen, was the daughter of Yiddish-speaking Russian and Polish immigrants and worked as literary editor of the

Nation

. Rafael was educated mainly at public schools, but the Yglesiases did send him to the prestigious Horace Mann School for three years. Inspired by his parents’ burgeoning literary careers, Rafael left school in the tenth grade in order to finish his first book. The largely autobiographical

Hide Fox, and All After

(1972) is the story of a bright young student who drops out of private school against his parents’ wishes to pursue his artistic ambitions.

Many of Yglesias’s subsequent novels would also draw heavily from his own life experiences. Yglesias wrote

The Work Is Innocent

(1976), a novel that candidly examines the pressures of youthful literary success, in his early twenties.

Hot Properties

(1986) follows the up-and-down fortunes of young literary upstarts drawn to New York’s entertainment and media worlds. In 1977, Yglesias married artist Margaret Joskow and the couple had two sons: Matthew, now a renowned political pundit and blogger, and Nicholas, a science-fiction writer. Yglesias’s experiences as a parent in Manhattan would help shape

Only Children

(1988), a novel about wealthy and ambitious new parents in the city. Margaret would later battle cancer, which she died from in 2004. Yglesias chronicled their relationship in the loving, honest, and unsparing

A Happy Marriage

(2009).

After marrying Joskow, Ylgesias took nearly a decade away from writing novels to dedicate himself to family life. During this break from book-writing, Yglesias began producing screenplays. He would eventually have great success adapting his novel

Fearless

(1992), a story of trauma and recovery, into a critically acclaimed motion picture starring Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez. Other notable screenplays and adaptations include

From Hell

,

Les Misérables

, and

Death and the Maiden

. He has collaborated with such directors as Roman Polanski and the Hughes brothers.

A lifelong New Yorker, Yglesias’s eye for city life—ambition, privilege, class struggle, and the clash of cultures—informs much of his work. Psychiatrists and psychoanalysts are often primary characters in Yglesias’s narratives, and titles such as

The Murderer Next Door

(1991) and

Dr. Neruda’s Cure for Evil

(1998) draw heavily on the intellectual traditions of psychology.

Yglesias lives in New York’s Upper East Side.

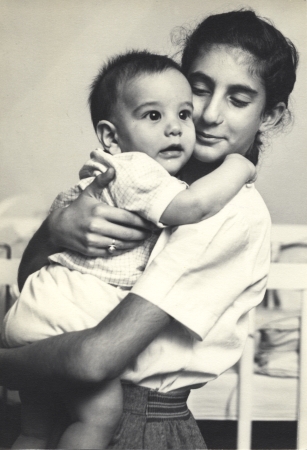

Yglesias with Tamar Cole, his half-sister from his mother’s first marriage, around 1955. He was raised with Tamar and his half-brother, Lewis.

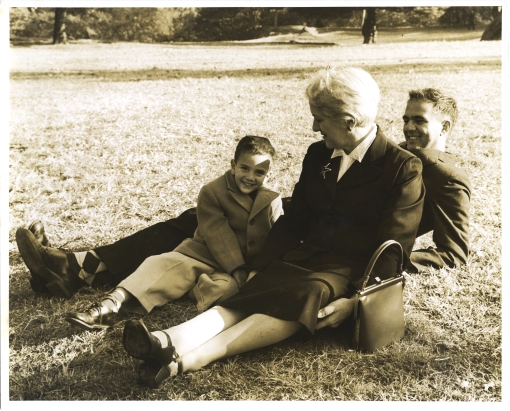

Yglesias sits atop his half-brother Lewis Cole’s shoulders around 1956. As adults, Yglesias and Cole worked together writing screenplays for ten years. All of them were sold, but none were ultimately made.

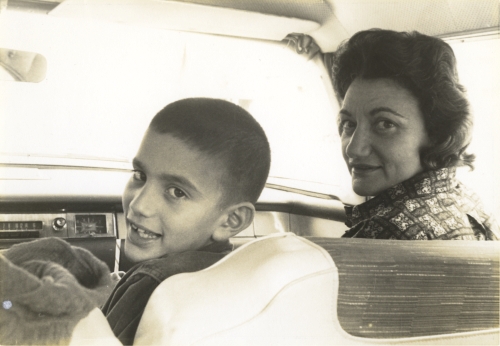

Yglesias at age ten, in a car with his mother in his father’s hometown of Ybor City in Tampa, Florida. Around this time, Yglesias lived in Spain for a year, an experience that proved formative in his young life.