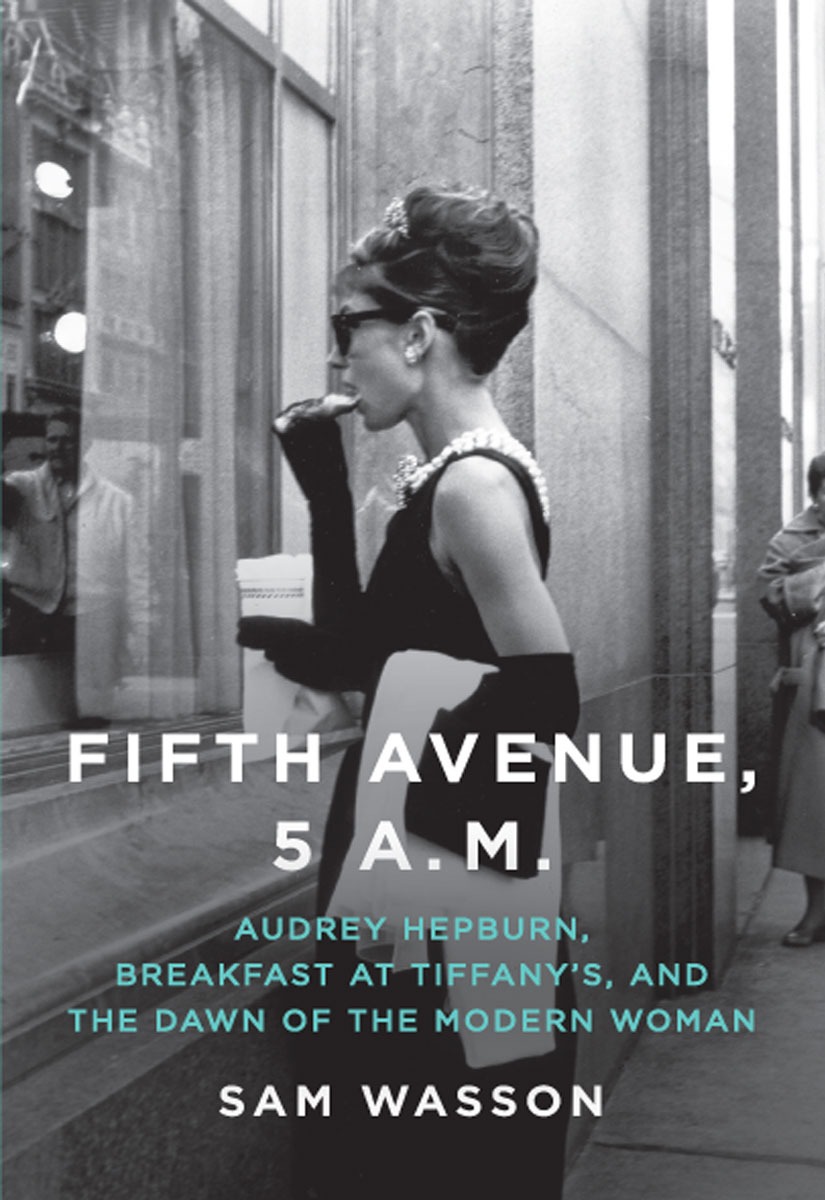

Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M.: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's, and the Dawn of the Modern Woman

Authors: Sam Wasson

Tags: #History, #General, #Performing Arts, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Films; cinema, #Film & Video - General, #Cinema, #Pop Culture, #Film: Book, #Pop Arts, #1929-1993, #Social History, #Film; TV & Radio, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Breakfast at Tiffany's (Motion picture), #Hepburn; Audrey, #Film And Society, #Motion Pictures (Specific Aspects), #Women's Studies - History, #History - General History, #Hepburn; Audrey;

Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's, and the Dawn of the Modern Woman

To Halpern, Cheiffetz, and Ellison,

without whom, etc.

IF THERE IS ONE FACT OF LIFE THAT AUDREY HEPBURN IS DEAD CERTAIN OF

, adamant about, irrevocably committed to, it's the fact that her married life, her husband and her baby, come first and far ahead of her career.

She said so the other day on the set of

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

the Jurow-Shepherd comedy for Paramount, in which she plays a New York play girl, café society type, whose constancy is highly suspect.

This unusual role for Miss Hepburn brought up the subject of career women vs. wivesâand Audrey made it tersely clear that she is by no means living her part.

PARAMOUNT PICTURES PUBLICITY,

NOVEMBER

28, 1960

Â

Â

Audrey Hepburn

as The Actress who wanted a home

Truman Capote

as The novelist who wanted a mother

Mel Ferrer

as The Husband who wanted a wife

Babe Paley

as The swan who wanted to fly

George Axelrod

as The screenwriter who wanted sex to be witty again

Edith Head

as The Costumer who wanted to work forever, stay old-fashioned, and never go out of style

Hubert de Givenchy

as The Designer who wanted a muse

Marty Jurow and Richard Shepherd

as The producers who wanted to close the deal for the right money and get the right people to make the best picture possible

Blake Edwards

as The Director who wanted to make a sophisticated grown-up comedy for a change

Henry Mancini

as The Composer who wanted a chance to do it his way

and Johnny Mercer

as The lyricist who didn't want to be forgotten

COSTARRING

Colette

Doris Day

Marilyn Monroe

Swifty Lazar

Billy Wilder

Carol Marcus

Gloria Vanderbilt

Patricia Neal

George Peppard

Bennett Cerf

Mickey Rooney

Akira Kurosawa

as The offended

AND INTRODUCING

Letty Cottin Pogrebin

as The Girl who saw the dawn

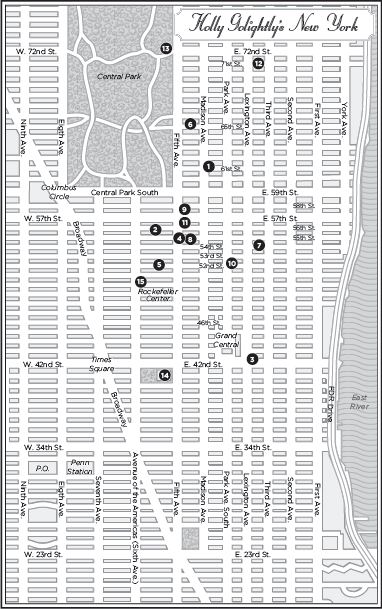

1. COLONY RESTAURANT,

MADISON AVENUE & 61ST STREET

Where producer Marty Jurow won the rights to

Breakfast at Tiffany's.

2. GOLD KEY CLUB,

26 WEST 56TH STREET

Carol Marcus and Capote would meet here at 3:00

A.M

., sit in front of the fireplace, and talk and talk.

3. COMMODORE HOTEL,

LEXINGTON AVENUE & 42ND STREET

Where paramount held an open cat-call to cast the part of Holly's cat, Cat.

4. PALEY PIED-Ã-TERRE

A three-room suite on the tenth floor of the St. Regis Hotel where Bill and Babe Paley lived when they weren't at their estate on Long Island.

5.

21 CLUB, 21 WEST 52ND STREET

In the film of

Breakfast at Tiffany's

, where Paul, after Holly bids farewell to Doc, takes Holly for a drink.

6. GLORIA VANDERBILT,

65TH STREET BETWEEN FIFTH & MADISON AVENUES

A brownstone that served as the model for Holly's, and the place where Carol Marcus met Capote.

7. EL MOROCCO,

154 EAST 54TH STREET

Where Marilyn Monroe kicked off her shoes and danced with Capote.

8. LA CÃTE BASQUE,

5 EAST 55TH STREET AT FIFTH AVENUE

Favorite lunch spot of Truman and his swans. Also the setting for Capote's incendiary “La Côte Basque, 1965,” which nearly cost him everyone he professed to love.

9. PLAZA HOTEL,

58TH STREET & FIFTH AVENUE

Frequented by Gloria Vanderbilt and Russell Hurd, one of Capote's inspirations for

Breakfast at Tiffany's

unnamed narrator.

10. FOUNTAIN

ON NORTHEAST CORNER OF 52ND STREET & PARK AVENUE

Exterior location for

Breakfast at Tiffany's.

11. TIFFANY & CO.,

727 57TH STREET AT FIFTH AVENUE

Site of the first scene of

Breakfast at Tiffany's

, shot on the first day of filming, Sunday, October 2nd, 1960, 5:00

A.M.

12. BROWNSTONE

AT 169 EAST 71ST STREET, BETWEEN LEXINGTON & THIRD AVENUES

Chez Golightly in the movie

Breakfast at Tiffany's.

13. NAUMBURG BANDSHELL IN CENTRAL PARK,

72ND STREET & FIFTH AVENUE

Exterior location for

Breakfast at Tiffany's

where Doc and Paul have their chat about Holly.

14. NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

ON 42ND STREET & FIFTH AVENUE

Exterior location for

Breakfast at Tiffany's.

15. RADIO CITY MUSIC HALL,

1260 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

Site of

Breakfast at Tiffany's

New York premiere, October 5, 1961.

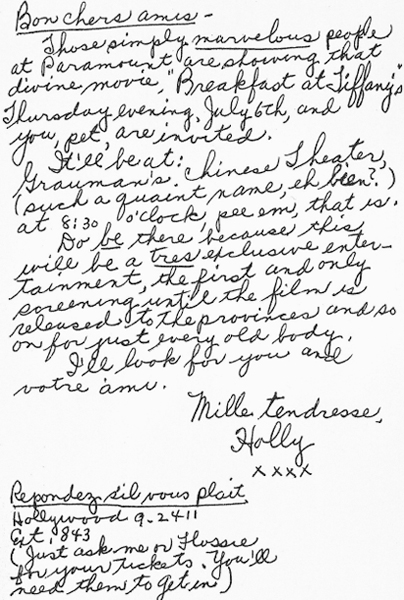

Invitation to

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Hollywood premiere, October, 1961.

Like one of those accidents that's not really an accident, the casting of “good” Audrey in the part of “not-so-good” call girl Holly Golightly rerouted the course of women in the movies, giving voice to what was then a still-unspoken shift in the 1950s gender plan. There was always sex in Hollywood, but before

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

only the bad girls were having it. With few exceptions, good girls in the movies had to get married before they earned their single fade to black, while the sultrier among them got to fade out all the time and with all different sorts of men in just about every position (of rank). Needless to say, they paid for their fun in the end. Either the bad girls would suffer/repent, love/marry, or suffer/repent/marry/die, but the general idea was always roughly the same: ladies, don't try this at home. But in

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

all of a suddenâbecause it was Audrey who was doing itâliving alone, going out, looking fabulous, and getting a little drunk didn't look so bad anymore. Being single actually seemed shame-free. It seemed fun.

Though they might have missed it, or not identified it as such right away, people who encountered Audrey's Holly Golightly in 1961 experienced, for the very first time, a glamorous fantasy life of wild, kooky independence and sophisticated sexual freedom; best of all, it was a fantasy they could make real. Until

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

glamorous women of the movies occupied strata available only to the mind-blowingly chic, satin-wrapped, ermine-lined ladies of the boulevard, whom no one but a true movie star could ever become. But Holly was different. She wore simple things. They weren't that expensive. And they looked stunning.

Somehow, despite her lack of funds and backwater pedigree, Holly Golightly still managed to be glamorous. If she were a society woman or fashion model, we might be less impressed with her choice of clothing, but because she's made it up from poverty on her ownâand is a

girl

no lessâbecause she's used style to overcome the restrictions of the class she was born into, Audrey's Holly showed that glamour was available to anyone, no matter what their age, sex life, or social standing. Grace Kelly's look was safe, Doris Day's undesirable, and Elizabeth Taylor'sâunless you had that bodyâunattainable, but in

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

Audrey's was democratic.

And to think that it almost didn't come off. To think that Audrey Hepburn didn't want the part, that the censors were railing against the script, that the studio wanted to cut “Moon River,” that Blake Edwards didn't know how to end it (he actually shot two separate endings), and that Capote's novel was considered unadaptable seems almost funny today. But it's true.

Well before Audrey signed on to the part, everyone at Paramount involved with

Breakfast at Tiffany's

was deeply worried about the movie. In fact, from the moment Marty Jurow and Richard Shepherd, the film's producers, got the rights to Capote's novel, getting

Tiffany's

off the ground looked downright impossible. Not only did they have a highly flammable protagonist on their hands, but Jurow and Shepherd hadn't the faintest idea how the hell they were going to take a novel with no second act, a nameless gay protagonist, a motiveless drama, and an unhappy ending, and turn it into a Hollywood movie. (Even when it was just a book,

Breakfast at Tiffany's

was causing a stir. Despite Capote's enormous celebrity,

Harper's Bazaar

refused to publish the novel on account of certain distasteful four-letter words.)

Morally, Paramount knew it was on shaky ground with

Tiffany's;

so much so that they sent forth a platoon of carefully worded press releases designed to convince Americans that real-life Audrey wasn't anything like Holly Golightly. She wasn't a hooker, they said; she was a kook. There's a difference! But try as they might, Paramount couldn't hoodwink everyone. “The

Tiffany

picture is the worst of the year from a morality standpoint,” one angry person would write in 1961. “Not only does it show a prostitute throwing herself at a âkept' man but it treats theft as a joke. I fear âshoplifting' will rise among teen-agers after viewing this.” Back then, while the sexual revolution was still underground,

Breakfast at Tiffany's

remained a covert insurgence, like a love letter passed around a classroom. And if you were caught in those days, the teacher would have had you expelled.

So with all that was against

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

how did they manage to pull it off? How did Jurow and Shepherd convince Audrey to play what was, at that time, the riskiest part of her career? How did screenwriter George Axelrod dupe the censors? How did Hubert de Givenchy manage to make mainstream the little black dress that seemed so suggestive? Finallyâand perhaps most significantlyâhow did

Breakfast at Tiffany's

bring American audiences to see that the bad girl was really a good one? There was no way she could have known it thenâin fact, if someone were to suggest it to her, she probably would have laughed them offâbut Audrey Hepburn, backed by everyone else on

Breakfast at Tiffany's,

was about to shake up absolutely everything. This book is the story of those people, their hustle, and that shake.