Fighter's Mind, A (15 page)

Authors: Sam Sheridan

At the weigh-in Rory’s opponent, Jay Ellis, finally showed, a muscular, smaller black man with glasses, a little on edge. Jay had a losing record, and he’d lost several fights in a row, but the worst part is he weighed in shockingly low, 161. Most people didn’t catch it but the few fighters who are friends with Rory laughed and a murmur ran around the room. Ellis was a replacement for Taiwon Howard who got hurt, a one-week-notice guy and probably the only opponent the promoter could find. He fights at 155, normally.

Rory can rehydrate and did so with relish; he made 180.6. In a way, the fight was its own kind of test for Rory—could he maintain his professionalism, could he stay focused without a credible threat?

When the fight happened, Jay Ellis—doing his “crazy” routine —ran at Rory and leaped, basically, completely over him. Rory pounced and started to work, but they were too close to the cage and Jay used his feet to run up the fence and reverse Rory. Then, lo and behold, Rory slipped on the triangle from the bottom and Jay was tapping before it was even closed—because Rory was using the squeeze properly, as Zé had shown him. To Jay, it felt tight, and it felt hopeless. Rory’s feet weren’t even in the proper position, he hadn’t secured the hold. But the squeeze was there.

WITNESS TO THE EXECUTION

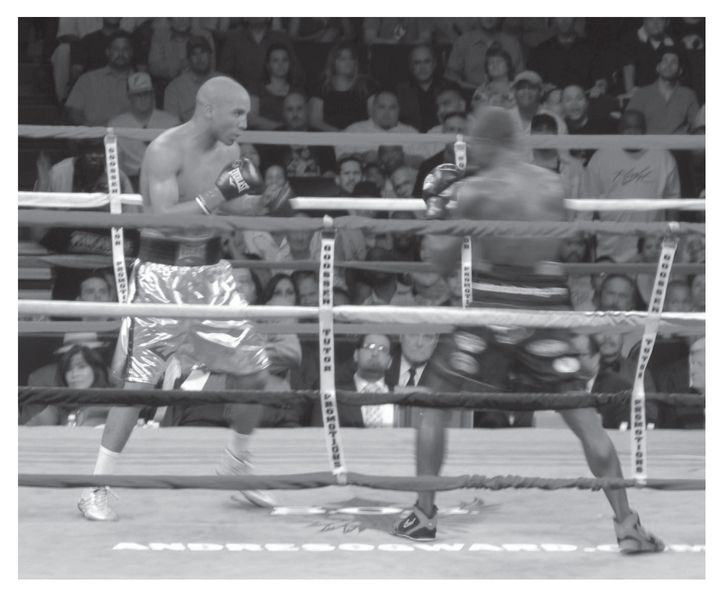

Andre Ward in a virtuoso performance against

Edison Miranda. (Courtesy: Andre Ward)

Edison Miranda. (Courtesy: Andre Ward)

Unpredictably, the moment of grace breaks upon you, and the

question is whether you are ready to receive it.

question is whether you are ready to receive it.

—Andrew Cooper

Gunpowder was invented in China, maybe as far back as 850, and it traveled to Japan in the form of fireworks. It was never actually weaponized, and when the Portuguese introduced firearms in 1500 the Japanese reacted strongly. The ruling caste saw the social hazards—and an end to their way of life—in the potential equalizer, and so banned it. They continued their endless feudal autumn, wherein most lives had little value, and samurai dueled to the death with the weapons of their grandfathers and great-great-grandfathers—the long and short swords. While the rest of the world plunged into the abyssal arms race, the samurai caste refined their techniques, using the tools they had perfected. These swords were the sharpest-edged weapons ever created by man. Smiths, considered national treasures and guarding their secrets, poured their souls into the blades, folding and pounding the steel thousands of times, over months, years. Horrifically deadly, dueling with those weapons was about as far out on the edge as you could go, walking a hair-thin line between life and death, risking everything to take everything. The modern mind reels at the thought of facing off with three-foot-long razors, where one of us will die. The levels of concentration, stress, and refinement of technique were stratospheric. Miyamoto Musashi, perhaps the greatest swordsman in this era of great swordsmen, wrote a book on fighting and strategy called

Go Rin No Sho

(

The Book of Five Rings)

. Musashi was a warrior who rose to prominence by winning all his duels, some sixty of them. He was the culmination of a caste and way of life that devoted the entirety of its energies to study of the sword. He achieved a level of mastery that may never be seen again.

Go Rin No Sho

(

The Book of Five Rings)

. Musashi was a warrior who rose to prominence by winning all his duels, some sixty of them. He was the culmination of a caste and way of life that devoted the entirety of its energies to study of the sword. He achieved a level of mastery that may never be seen again.

When I started writing this book I was thinking about it as an updated

Book of Five Rings,

which has become a kind of knee-jerk part of any traditional martial arts philosophy; it was even adopted in the 1980s (when the Japanese business model was booming) as a self-help book for businessmen. A lot of people have found inspiration and guidance in the book, for all sorts of reasons, but one must never lose sight of what

Go Rin No Sho

is finally about:

cutting

.

Book of Five Rings,

which has become a kind of knee-jerk part of any traditional martial arts philosophy; it was even adopted in the 1980s (when the Japanese business model was booming) as a self-help book for businessmen. A lot of people have found inspiration and guidance in the book, for all sorts of reasons, but one must never lose sight of what

Go Rin No Sho

is finally about:

cutting

.

Andre Ward was the only American boxer to win gold in the 2004 Olympics. I have known Andre and his trainer and god-father, Virgil Hunter, since 2003. I wrote extensively about them in my first book, curious about the development of a red-hot boxing prospect in the early stages of a professional career. I had spent several months at King’s Boxing Gym, a throwback gym, dank, gritty, and functional. I lived near them in Oakland, in the desert heat, and drove through the dusty streets and sprinted hills and ran the parks. Virgil said to me once, “I knew Andre would win gold at the Olympics because I was influenced in my training by

The Book of Five Rings,

and that’s the symbol for the Olympics. Five rings.”

The Book of Five Rings,

and that’s the symbol for the Olympics. Five rings.”

Virgil and I have an interesting friendship; he’s in his fifties, black, from a militant background—Oakland and Berkeley in the ’60s and the overtones of black power. He’d come up from the streets and I was a white kid from the East Coast who went to Harvard. We were using each other in a classic boxing way: mercenary but mutually beneficial. I was getting good material for my book and Virgil was getting exposure for himself and his fighters. He knew how I saw him, as a wise trainer, and he could play that role, but he also knew it was no bullshit. Virgil really did have a profound understanding of the game. He had the goods and he knew it.

Boxing is about reputations, and Virgil knew that the more I wrote about him the better for him, but only so long as his fighters were winning. Fighting has that beautiful bottom line: win. I don’t care how wonderful a human being Muhammad Ali was, without his big wins—if he had lost those marquee title fights—he wouldn’t be the sportsman of the century. No one would care if he refused the draft or not. No one would care if he changed his name. So I won’t overestimate my importance but I could be a help. Plus we had a genuine liking for each other, a respect because I could understand him; to a certain extent I could pick up what he was putting down.

Virgil met Andre when he was nine years old and saw something in the little boy—the ghost of a killer’s punch, some premonition of speed. Andre, his dad, and Virgil had embarked on a career together. Andre’s father had been a boxer who loved the sport, and he wanted Andre to learn it properly, how to hit and not be hit.

Andre, or Dre to his friends, trekked to the boxing gym after school and he stuck with it, day in and day out. He was caught in the inevitability of it, like a soldier swept to war, but he was also called by something inside of him. He came to love and hate the gym. The gym is the anvil on which boxers are forged, tempered like a samurai sword with thousands of hammer blows, bending steel into steel. Fighters are born in the dedication to repetition. It’s not about who is stronger and faster, although those things can cover for other problems. Nothing can replace natural self-discipline; nothing can replace time in the gym. Andre loved boxing, and you have to love it to be great. To compete at the highest level requires eight or ten years of groundwork, going to the gym and working to get better every day, day in and day out, with no end in sight. You have to love the journey.

Malcolm Gladwell’s book

Outliers

is a fascinating look at success. He talks at length about the search for innate talent, and a mind-blowing study he cites is an investigation by psychologists at the elite Berlin Academy of Music. These psychologists looked at the violinists and found a very simple correlation—the more they practiced, the better they were. They checked it with the pianists and found the same thing—everybody had some talent and started playing around age five. “But when the students were around the age of eight, real differences started to emerge. The students who would end up the best in their class began to practice more than everyone else . . . until by the age of twenty they were practicing . . . over thirty hours a week.” These were the players who were the virtuosos, the ones who would go on to become famous performers, world-class talents, “geniuses.” The lower half, who did only eight hours a week, were destined to be music teachers.

Outliers

is a fascinating look at success. He talks at length about the search for innate talent, and a mind-blowing study he cites is an investigation by psychologists at the elite Berlin Academy of Music. These psychologists looked at the violinists and found a very simple correlation—the more they practiced, the better they were. They checked it with the pianists and found the same thing—everybody had some talent and started playing around age five. “But when the students were around the age of eight, real differences started to emerge. The students who would end up the best in their class began to practice more than everyone else . . . until by the age of twenty they were practicing . . . over thirty hours a week.” These were the players who were the virtuosos, the ones who would go on to become famous performers, world-class talents, “geniuses.” The lower half, who did only eight hours a week, were destined to be music teachers.

And the incredible thing was there were no “naturals” who were at the top without this commitment. Nobody in the top third didn’t practice thirty hours a week since childhood, and there weren’t any “grinds,” guys who worked that hard but just couldn’t make it. There’s a magical number: ten thousand hours of diligent, intentional, informed practice. “That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the very top don’t just work harder, or even much harder than everyone else. They work much,

much

harder.”

much

harder.”

The ten-thousand-hours thing apparently comes up in just about every field and discipline. I had a painting teacher who told me in college, “You just got to push paint around for ten years before you figure it out.” Even a prodigy like Mozart got in ten thousand hours; he just started early. Gladwell wasn’t the first to notice this. The basic signifier for expertise had been set at ten years of practice by everyone studying these things, but his book is well written and really brought the point home.

With boxers, with fighters, you have to have get your ten thousand hours in before you’re too old to fight, which is why you have to start so young. And there is a certain amount of athletic ability and toughness needed. Gladwell makes the point in basketball—if you’re five-foot-five, you can practice ten thousand hours with the best coaches in the country and still probably not play in the NBA. But if you’re over six-five? If you have the bare minimum of ability? Then it comes down, overwhelmingly, to commitment.

Virgil started sparring Andre at around age eleven, with a kid named Glen Donaire (who’s won flyweight, 112-pound titles, as has his brother Nonito, the current IBF flyweight champ). Glen was older, and about the same size, but more advanced and physically mature—he would “put it on” Dre with ease. “I wouldn’t let Dre take a real beating, but I’d let him get frustrated. He’d get hit.” At this point, Glen so far outclassed Dre that Glen wasn’t concerned at all with what Dre would throw back.

Virgil talked at the local coffee shop, Coffee With a Beat, sipping his tea, his eyes hidden behind his glasses. Watchful, his voice was quiet with the sibilance of confidence.

“Dre was running all around the ring, ducking and dodging, turning, grabbing, holding on—not punching but

surviving

. So I encouraged that. ‘Don’t let him hit you,’ I told Dre. I never mentioned fighting back. I wanted to know if he could take it before he started dishing it, to handle the pressure. He can’t beat you up if he can’t catch you.” Virgil as a trainer needs to always evaluate where his fighter is, mentally. Especially at a young age, you need to see what you’ve got, because otherwise Virgil could waste years of his life training someone who will never be successful.

surviving

. So I encouraged that. ‘Don’t let him hit you,’ I told Dre. I never mentioned fighting back. I wanted to know if he could take it before he started dishing it, to handle the pressure. He can’t beat you up if he can’t catch you.” Virgil as a trainer needs to always evaluate where his fighter is, mentally. Especially at a young age, you need to see what you’ve got, because otherwise Virgil could waste years of his life training someone who will never be successful.

Virgil smiles. “Sometimes there were tears, but they were

retaliatory

tears.” He laughed.

retaliatory

tears.” He laughed.

“I would cheerlead Dre, ‘man he missed you by a foot!’ and watch Glen. Glen was so confident, he would finally walk Dre down, when Dre got tired, and stand right in front of him and look him over. Glen would stand there and look for an opening to land his punches.” This went on for weeks, with Dre learning how to move, to get out of the way, to avoid damage from a better, stronger, more experienced guy.

“So I taught Dre this little hook-jab-type punch, and I told him every time he stops in front of you hit him with this little punch, and then go move again. Lo and behold, the next sparring session, Glen pulls up in front of Dre and pow, Dre pops him and then he goes. Of course, this incited Glen—we’ve been sparring three weeks and you’ve never hit me—so he would swarm Dre and try and get that last hard punch in. The next couple of weeks, that was the routine, hit him and move fast. Just as Glen was pouring it on, I’d stop it. I’d let Dre take one good hard shot, and then I’d stop it, middle of the round or whatever. I was looking for one thing.”

I can imagine Dre’s life—the constancy of the boxing gym after school, the routines and smells of leather and Vaseline, hand wraps and boxing shoes. Ever present was his white father, Frank Ward, who’d been a heavyweight with ten amateur fights, who pushed him and be-lieved in him, and tall Virgil watching and teaching him. Virgil had been an officer at a juvenile delinquent hall his whole working life; one thing he understood was young mens’ psyches.

Other books

The Look of Love: A Novel by Sarah Jio

Their Runaway Mate by Cross, Selena

Soul Bonded by Malone, Meghan

On the Case (From the Files of Madison Finn, 17) by Dower, Laura

Zane Grey by The Spirit of the Border

Biker Bound: The Lost Souls MC Series by Ellie R Hunter

Southern Shifters: Lone Wolf Wanted (Kindle Worlds Novella) by Jessie Lane

Tom Swift and His Diving Seacopter by Victor Appleton II

Hard Case Crime: The Max by Ken Bruen, Jason Starr

Season of Glory by Lisa Tawn Bergren