Financial Markets Operations Management (16 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

We have seen that any financial transaction involves the collection and distribution of information which encompasses financial instruments and counterparties/customers. Today, the financial industry is truly global, and it is important that any information is in a standardised format so that it can be readily recognisable by our processing systems in a straight-through processing environment.

Information on financial instruments, counterparties and customers can be obtained from a variety of sources, ranging from direct access or indirect access to one of the information vendor companies.

We have also seen that financial instruments have, by and large, been standardised using the ISIN and local numbering systems together with the classification codes (CFI codes). However, the standardisation of counterparties and customers (the so-called legal entities) has only been addressed in recent years. The LEI initiative set up by the G20 countries and the FSB is now in progress, with the allocation of pre-LEIs by some LOUs (e.g. the UK and Turkey).

Market Participation

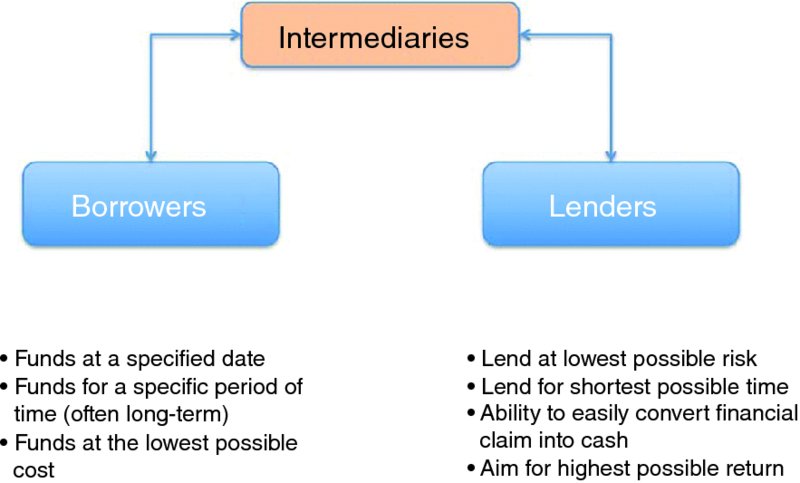

In the financial world, there is a relationship between those entities that require funds and those that have funds. We can refer to these entities as

borrowers

and

lenders

respectively.

For these reasons, there will be a number of intermediaries that stand between the lenders and borrowers and help to transform the size of loans from small to large, transform the short-term wishes of the lenders into the longer-term needs of the borrowers and, finally, provide the ability to diversify the credit risk of the borrowers.

These relationships are shown in

Figure 4.1

and we will discuss these in subsequent sections of this chapter.

FIGURE 4.1

Borrowers, lenders and intermediaries

By the end of this chapter, you will:

- Understand the different types of lender and borrower and what motivates them;

- Know why intermediaries are necessary, who they are and what functions they perform;

- Understand the market infrastructures and the roles they perform.

Most of us have bank accounts into which our salaries, wages and other income is paid and out of which our day-to-day expenses such as rent, mortgage repayments, food, mobile telephone bills, etc. are deducted. These accounts are often referred to as

current accounts

or (in the USA) as

checking accounts

. The balances on these accounts might be rather small; however, we can transfer cash into and out of these current accounts very easily as we do not have to give our bank any forewarning (known as

notice

) of these activities. The banks for their part will use the credit balances on their clients' current accounts as part of their funding activities, i.e. lending the cash to those who need to borrow. For example, a client needs to borrow EUR 10,000 and requests the bank to lend this amount. The bank does not debit the current accounts directly; instead, the clients' cash balances are held collectively in a nostro account and it is from this account that the borrower is credited with the loan. Please note that the current account holders are not directly lending funds; however, many banks will credit these accounts with interest. These rates will be less than the interest the bank will charge the borrower. The difference (or spread) in these rates represents the net interest income on the bank's Profit & Loss account.

In addition to our current accounts, we might have a deposit or savings account. We would use this to hold cash that we may not require straight away; indeed, it could be used to build up a considerable balance in order to pay for a deposit on a property, or other significant purpose. Not only will there be higher balances compared with the current account balances, but the balances will tend to remain in the account for longer periods. The bank will utilise these

balances as well in the knowledge that the deposit account holder will not require the cash straight away (unlike the current account holder).

How else might a retail client use his funds? If, for example, the client has more cash than he needs for his day-to-day expenses, he might decide to purchase some investments. He might do this using a broker, either directly or online. The client now becomes an investor. His motivation might include benefiting from:

- Income from the investment (dividends or interest);

- Capital growth (the price of the investment increasing).

It is arguable that the direct investor requires access to a comparatively large amount of cash in order to diversify his investments; perhaps in the order of many tens of thousands of units of cash. Potential investors are often advised never to invest any cash that (a) is required for other, more immediate purposes and (b) that the investor cannot afford to lose. What can an investor do if he does not have sufficient cash to invest directly in shares and bonds, etc.? There is an alternative â indirect investment.

There is a wide range of investment products that are known as collective investments. Examples include mutual funds, unit trusts, investment trusts, exchange trade funds, open-ended funds, etc.

What these collective investments all have in common is that financial entities (e.g. investment managers) invest their clients' cash in one or more collective investment funds. The cash is used to buy appropriate securities that are held within the fund and, in exchange, the fund manager gives shares/units in the fund to the clients. In this way, one particular client with a small amount of cash can benefit from the investment expertise of the fund manager and hold shares within a fund that is diversified in terms of underlying products and markets.

As we will see later, the risks associated with these three fundamental types of cash usage differ from a comparatively low level of risk (bank accounts) to a comparatively high level of risk (e.g. equities/shares).

Collectively, institutional investors are organisations that invest large pools of money on behalf of their clients into various classes of investment such as securities, property, commodities and so-called “alternative investments”. The institutional investors invest the money into “funds” that contain a broad, diverse range of assets tailored to meet predefined investment objectives. The idea behind asset diversification is that it helps to reduce the risk that the fund will suffer if a constituent investment defaults; the more diversified the fund, the lower the risk.

An example of an undiversified fund would be a fund that contains only one asset. If that asset lost, say, 50% of its value, then the fund would also lose 50% of its value. However, a diversified fund of, say, 25 assets including the one that loses 50% of its value, would only lose a fraction of its value. (Investment risk is an interesting topic and includes “hedging” as well as “fund diversification”.)

Investment management companies employ investment managers who invest and divest their clients' assets. This can be discretionary (where the manager decides what action to take without reference to the client) or non-discretionary (where the manager suggests a course of action for approval by the client prior to taking action). In either situation, the investment manager will have assessed each client's individual investment needs and risk profile.

It is the investment manager's role to manage clients' assets in such a way that the clients' investment objectives are met. To do this, the manager will allocate assets across a range of asset classes, commonly divided into:

- Cash/money market instruments

- Equities

- Bonds

- Property

- Commodities.

In addition, there are two broad investment management styles:

- Active management:

Active management (also called active investing) refers to a portfolio management strategy where the manager makes specific investments with the goal of outperforming an investment benchmark index. There are various strategies that the active manager can use; however, the essential idea is to exploit market inefficiencies (purchase

undervalued

assets and/or sell

overvalued

assets). - Passive management:

By contrast, the passive manager creates a fund which only invests in the assets that constitute a particular stock market index. This way, the passive manager mimics the performance of the chosen index.

Whilst passive managers have traditionally used equity indices (of which there are many to choose from), there are indices that cover bonds, commodities and hedge funds.

Hedge fund managers employ an alternative investment style to the more traditional investment managers that we discussed above. The first hedge fund was established in 1949 by a Mr Alfred W. Jones, who designed the classic “longâshort” strategy. Jones would take a long position in an asset and hedge the risk of the long position by taking a short position in another asset. For example, you could buy shares long in Company “A” (running the risk that the share price goes down) and sell shares short in Company “B” (running the risk that the share price goes up).

Hedge fund managers can either adopt a single investment strategy approach (such as the longâshort described above) or a multi-strategy approach. Whilst there are many variations, the main strategies are:

- Global macro:

Managers take large positions in securities in anticipation of global macroeconomic events. To do this, managers might have to borrow sizeable amounts of cash (leverage). - Directional:

Managers select investments based on market movements, trends or inconsistencies across markets. - Event-driven:

Managers aim to take advantage of pricing inconsistencies due to corporate action events such as distressed securities, mergers, acquisitions, etc. - Relative value:

Managers aim to take advantage of the discrepancies between related securities.

Hedge fund managers can make substantial profits through using these investment styles; however, the reverse is also true â they can make substantial losses. The risk is that if the losses are too great, the fund might fail. For this reason, hedge funds are not generally available to retail investors.

The hedge fund industry manages over USD 2.9 trillion of assets (AUM) as at the 1Q 2014;

1

the ten largest hedge fund managers are shown in

Table 4.2

.

TABLE 4.2

Ten largest hedge fund managers by AUM

| Rank | Hedge Fund | AUM USD bns |

| Â 1 | Bridgewater Associates (Westport, Connecticut) | 77.6 |

| Â 2 | Man Group (London) | 64.5 |

| Â 3 | JP Morgan Asset Management (New York) | 46.6 |

| Â 4 | Brevan Howard Asset Management (London) | 32.6 |

| Â 5 | Och-Ziff Capital Management Group (NewYork) | 28.5 |

| Â 6 | Paulson & Co. (New York) | 28.0 |

| Â 7 | BlackRock Advisors (New York) | 27.7 |

| Â 8 | Winton Capital Management (London) | 27.0 |

| Â 9 | Highbridge Capital Management (New York) | 26.1 |

| 10 | BlueCrest Capital Management (London) | 25.0 |

A pension fund is designed to provide retirement income to individuals who have reached retirement age. There are different classifications including open, closed, public and private pension funds. You do not need to understand these classifications for this module, but you should be aware of some of the investment challenges experienced by the funds themselves.

In basic terms, an employer contributes cash into a pension fund on a regular basis (e.g. monthly) and a fund manager invests that cash in the markets. In addition, individuals can contribute either as employees into their employer's fund or into a personal pension fund. The objective is to provide the individual with an income at some specified time in the future, typically once the individual reaches retirement age.

The challenge for the employer is to decide how much cash to contribute now in order for the retiree to draw a pension in the future. In a

defined benefits

scheme, the retiree will receive a specified monthly benefit that is predetermined by a formula based on three factors: the employee's earnings history, tenure of service and age. The employer cannot know these factors in advance; to cover the cost of a defined benefits scheme, it has to make investment decisions based on advice given by actuarial professionals.

By contrast, in a

defined contribution

scheme, the employer contributes a specified amount of cash and relies on investment returns to provide a pension for the employee. The cost for the employer is therefore known; however, the benefit for the employee is unknown until retirement occurs and

the calculations made.

Whichever scheme is adopted, the contributions are invested in order to provide a sufficient amount of cash with which an annuity is purchased. It is the annuity that provides the income during retirement. In the meantime, the fund managers will invest the contributions in a range of investment products including short-term instruments (money markets), long-term instruments and equities (cash markets), derivative products and alternative investments. There are rules as to which investment products can be invested in and limits as to how much can be invested in the product (see

Table 4.3

).

TABLE 4.3

Example of investment allocation for a pension fund

| Investment Product | % per Investment Product | Fund % Holding |

| Equities | 60% | |

| ⦠of which | Domestic â 70% International â 30% Sub-total â 100% | |

| Bonds | 30% | |

| ⦠of which | Domestic government â 30% Domestic corporate â 25% International government â 25% International corporate â 15% Eurobonds â 5% Sub-total â 100% | |

| Cash and money markets | 5% | |

| ⦠of which | Cash â 50% Certificates of deposit â 50% Sub-total â 100% | |

| Derivatives and alternatives | 5% | |

| ⦠of which | Financial futures â 40% Commodities â 40% Forestry â 20% Sub-total â 100% | |

| Total: | 100% |

Based on OECD data and TheCityUK's estimates,

2

global pension assets totalled USD 31.5 trillion at the end of 2011. This compares with global conventional assets under management of the global fund management industry of USD 79.8 trillion (with a forecast of USD 85.2 trillion for 2012). This illustrates the importance of the pension fund industry to the financial markets.

The largest pension fund in the world is the Japanese Government Pension Investment Fund with total assets of JPY 123,922.8 billion (USD 1,188.4 billion).

3

“Insurance” can be defined as the equitable transfer of the risk of a contingent, uncertain loss from one entity (the insured entity) to another (the insurer entity) in exchange for payment (the premium). The premia are invested in order to settle any future insurance claims.

There are many different types of insurance, but they can be divided into two principal categories, as the following examples illustrate:

Life

- Life insurance: A lump sum is paid to a decedent's designated beneficiary (e.g. a family member).

- Annuity: Regular payments are made to a beneficiary (e.g. retirement pension income).

Non-Life

- Property insurance: Home, aviation, flood, earthquake, marine, etc.

- Vehicle insurance: Third party, fire and theft, comprehensive.

- Liability insurance: Public liability, professional liability, etc.

- Credit insurance: Mortgage, credit card, trade credit, etc.

- Other types of insurance include travel, legal expenses, divorce, etc.

Insurance companies make their money through underwriting and investing, with their profits being earned by deducting incurred losses and underwriting expenses from the premia and investment income.

Based on OECD data and TheCityUK's estimates,

4

global insurance fund assets totalled USD 24.4 trillion at the end of 2011. This compares with global conventional assets under management of the global fund management industry of USD 79.8 trillion. This illustrates the importance of the insurance fund industry to the financial markets. The ten largest insurers by assets are listed in

Table 4.4

.

5

TABLE 4.4

Top ten insurers by assets

| Company | Country | Assets (USD bns) | Sector |

| ING Group | Netherlands | 1,533.7 | Life and Health |

| AXA Group | France | 1,005.4 | Diversified |

| Allianz | Germany | 915.8 | Diversified |

| MetLife | United States | 836.8 | Diversified |

| Prudential Financial | United States | 709.3 | Life and Health |

| Generali Group | Italy | 582.4 | Diversified |

| Legal & General Group | United Kingdom | 562.9 | Life and Health |

| American International Group | United States | 548.6 | Diversified |

| Aviva | United Kingdom | 512.7 | Life and Health |

| Prudential | United Kingdom | 489.4 | Life and Health |