Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (4 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

• Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

Key Metrics Shenanigans

• Showcasing Misleading Metrics That Overstate Performance

• Distorting Balance Sheet Metrics to Avoid Showing Deterioration

Tyco: Most Shameless Heist by Senior Management

Similar to WorldCom, Tyco International Ltd. loved doing acquisitions, making hundreds of them over a few short years. From 1999 to 2002, Tyco bought more than 700 companies for a combined total of approximately $29 billion. While some of the acquired companies were large businesses, many were so small that Tyco did not even bother disclosing them to investors in its financial statements.

Tyco probably liked the businesses that it was buying, but more than that, the company loved to be able to show investors that it was growing rapidly. However, what Tyco seemed to like best about these acquisitions was the accounting loopholes that they presented. The acquisitions allowed the company to reload its dwindling reserves, providing a consistent source of artificial earnings boosts. Moreover, the frequent acquisitions allowed Tyco to show strong operating cash flow, even though it merely resulted from an accounting loophole. (We will come back to this in Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 3: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals.) Indeed, Tyco loved the acquisition accounting benefits so much that it even used them when no acquisitions at all occurred.

Tyco’s Clever Accounting Games

Consider how Tyco accounted for payments that it made in soliciting new security-alarm business in its ADT subsidiary. Rather than hire additional employees, Tyco decided to use an independent network of dealers to solicit new customers. Tyco was so enamored with acquisition accounting that it decided to use this technique to record the purchase of these contracts from agents. In so doing, Tyco inflated its profits by failing to record the proper expense. Moreover, Tyco inflated its operating cash flow by recording these payments in the Investing section of the Statement of Cash Flows.

But Tyco had many more tricks up its sleeve. It increased the price paid to dealers for each contract, and in return, required the dealers to pay that increased amount back to it as a “connection fee” for doing business. While this arrangement clearly had no impact on the underlying economics of the transaction, Tyco inappropriately decided to record this connection fee as income, providing an artificial boost to both earnings and operating cash flow. The boosts really added up when you consider that Tyco played this game with hundreds of thousands of contracts that it purchased.

The SEC Charges Tyco with Fraud

The SEC reviewed Tyco’s arrangements with dealers and gave the company a “thumbs down” for its creative accounting. As part of an overall billion-dollar fraud, the SEC alleged that Tyco used inappropriate accounting for ADT contract purchases to fraudulently generate $567 million in operating income and $719 million in cash flow from operations. Moreover, the SEC charged that Tyco engaged in improper acquisition accounting practices that inflated operating income by at least $500 million. Such practices included undervaluing acquired assets, overvaluing acquired liabilities, and misusing accounting rules concerning the establishment and utilization of reserves. If that were not enough, the lawsuit charged that Tyco had improperly established and used various reserves to enhance and smooth publicly reported results and meet Wall Street expectations.

The Tyco Piggy Bank

Unfortunately for Tyco and its investors, the problems were far from over. During this period, senior executives (mainly CEO Dennis Kozlowski and CFO Mark Swartz) had been using the company’s cash account as their own piggy bank. The government charged that these executives had been stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from Tyco by failing to properly disclose to shareholders the existence of back-door executive compensation arrangements and related-party transactions. With the board unaware or asleep at the wheel, senior executives granted themselves loans for personal expenses, many of which were secretly forgiven, effectively producing a large unreported compensation expense.

Enormous Penalty and Jail Time

The larcenous executives at Tyco paid an enormous price. On top of a $50 million SEC penalty, the company agreed to pay a record-breaking $3 billion in restitution to settle shareholder lawsuits. Moreover, Kozlowski and Swartz were convicted of looting the company and inflating its stock price, and both were sentenced to up to 25 years in prison.

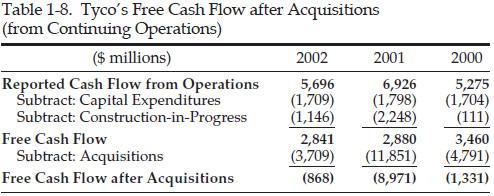

Warning for Tyco Investors—Negative Free Cash Flow, Net of Acquisitions

Detailed cash flow analysis would have helped investors notice problems at Tyco. For acquisitive companies, however, we suggest computing an adjusted free cash flow that removes total cash outflows for acquisitions. By adjusting the free cash flow calculation for acquisitions, investors would have a clearer picture of a company’s performance. As a theme discussed throughout the book, acquisitions present numerous opportunities for companies to inflate earnings and both operating and free cash flow. In the case of Tyco, we spotted big drops in adjusted free cash flow. As shown in Table 1-8, between 2000 and 2002, Tyco generated a cumulative

negative

free cash flow (net of acquisitions), although it reported very large operating cash inflows for those years.

TYCO: FINANCIAL SHENANIGANS IDENTIFIED

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans

• Recording Bogus Revenue

• Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period

• Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

• Shifting Current Income to a Later Period

• Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

Cash Flow Shenanigans

• Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

• Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

• Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

• Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

Key Metrics Shenanigans

• Showcasing Misleading Metrics That Overstate Performance

• Distorting Balance Sheet Metrics to Avoid Showing Deterioration

Symbol Technologies: Most Ardent and Prolific Use of Numerous Shenanigans

Although much smaller in size, Long Island–based Symbol Technologies Inc., a maker of bar code scanners, earned its rightful place as a winner of our

As Bad as It Gets

Award in creative accounting for its audacious use of all seven Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans, all four Cash Flow Shenanigans, and both Key Metrics Shenanigans—an impressive and rare distinction. Even Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco could not match the breadth of Symbol’s feat. (Of course, these three companies distinguished and disgraced themselves by “specializing” in a few gigantic shenanigans.)

Some Tricks Used

Symbol seemed to be obsessed with never disappointing Wall Street. For more than eight consecutive years, it either met or exceeded Wall Street’s estimated earnings—32 straight quarters of sustained success. In hindsight, though, such steady and predictable performance (particularly during the technology collapse of 2000–2002) should have alerted investors to take a closer look.

Symbol never wanted its earnings to get too high or too low, so it would record bogus adjustments to the company’s financial statements at the end of each quarter in order to align its results with Wall Street expectations. In very strong periods, for example, the company would take charges to create “cookie jar” reserves that could be used to boost earnings during weaker periods. That occurred in the late 1990s when Symbol won a large contract from the U.S. Postal Service that accounted for 11 percent of the company’s 1998 revenue. Symbol cleverly used restructuring charges to dampen its reported growth, and in so doing, both lowered the bar to meet future-period Wall Street expectations and created reserves that could be released when needed.

If, instead, Symbol’s business slowed and Wall Street targets went unmet, the company would “stuff the channel,” or ship products to customers too early in order to record additional revenue. Symbol also allegedly inflated revenue by shipping products that its customers did not want. The company even sold products to customers in order to record revenue, then repurchased the goods at a higher price (a bizarre arrangement in which Symbol actually lost money in order to create revenue growth).

Moreover, if Symbol’s operating expenses got out of control and needed some trimming, there was a ready solution. In one case, when paying bonuses in early 2001, Symbol conveniently (and improperly) deferred the related Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) insurance costs, thereby inflating operating income. The company also tidied up messy issues that surfaced on the Balance Sheet, like accounts receivable that were not getting collected. In 2001, Symbol was concerned that Wall Street would react unfavorably to surging receivables, so it simply moved them to another section of the Balance Sheet where they would be hidden from investors’ view. (More on this in Part 4, “Key Metrics Shenanigans.”)

And Justice for All—But One

The regulators finally caught up with Symbol after all those years of duping investors. The SEC accused Symbol of perpetrating a massive fraud from 1998 until 2003. Unlike the scoundrels running Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco, however, Symbol’s senior executive followed a different (and somewhat bizarre) course. After being indicted on securities fraud charges, CEO Tomo Razmilovic fled the country and was declared a fugitive. He even made the U.S. Postal Inspection Service’s “most-wanted” list, with a $100,000 reward offered for his arrest and conviction. (At that time, he was the only white-collar crime suspect on the agency’s most-wanted Web site, which included rewards for the anthrax mailer, certain bombing suspects, and post office robbers.) He is still on the lam, apparently living comfortably in Sweden.

Warnings for Symbol Technologies Investors

In addition to Symbol’s unusually steady and predictable performance, there were many warning signs for investors about the company’s struggles. Our forensic research firm, the Center for Financial Research and Analysis (CFRA, and now part of RiskMetrics Group), issued six separate reports between 1999 and 2001, warning investors about Symbol’s aggressive accounting practices. Specific issues raised in our reports include the following:

- Unusually large one-time charges seemed to be designed to create bogus reserves that could be used in future periods to benefit earnings. For example, when acquiring Telxon in 2000, Symbol wrote off 68 percent of the purchase price. Symbol also wrote off inventory that may have subsequently been sold, providing a boost to margins.

- Symbol showed signs of aggressive cost capitalization, including a doubling of capitalized software and a surge in soft assets to 21 percent of total assets in Q2 2000 (from 11 percent the prior year).

- Inventories jumped dramatically, raising concerns about margin pressure in future periods, possible product returns, or customers losing interest in the company’s product.

- Accounts receivable surged from early 1999 to 2001, signaling aggressive revenue recognition (stuffing the channels at the end of the period).

- Symbol’s allowance for doubtful accounts continuously declined as a percentage of accounts receivable, providing a benefit to earnings.

- Symbol frequently fell half a penny short of earnings per share (EPS) targets, but kept its Wall Street “success” streak alive by rounding up (for example, rounding up $0.1167 to achieve the target of $0.12). We considered it highly unlikely that management was this lucky and consistent, instead seeing it as a sign of earnings manipulation.

- Cash flow from operations routinely lagged behind net income, a sign of poor earnings quality.

SYMBOL: FINANCIAL SHENANIGANS IDENTIFIED

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans