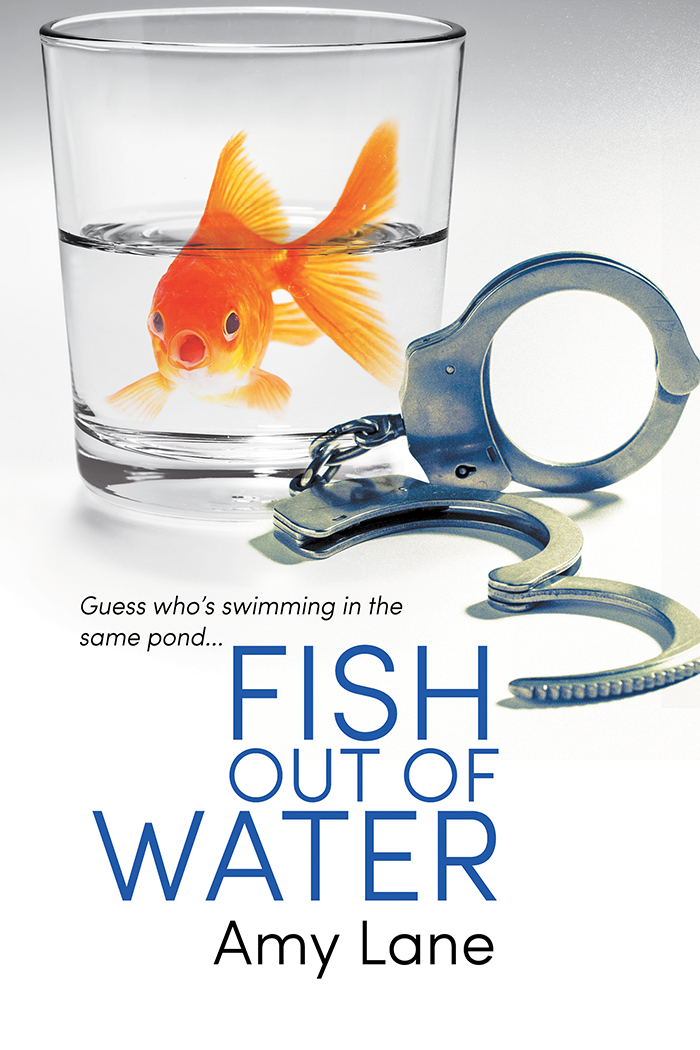

Fish Out of Water

By Amy Lane

PI Jackson Rivers grew up on the mean streets of Del Paso Heights—and he doesn’t trust cops, even though he was one. When the man he thinks of as his brother is accused of killing a police officer in an obviously doctored crime, Jackson will move heaven and earth to keep Kaden and his family safe.

Defense attorney Ellery Cramer grew up with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, but that hasn’t stopped him from crushing on street-smart, swaggering Jackson Rivers for the past six years. But when Jackson asks for his help defending Kaden Cameron, Ellery is out of his depth—and not just with guarded, prickly Jackson. Kaden wasn’t just framed, he was framed by crooked cops, and the conspiracy goes higher than Ellery dares reach—and deep into Jackson’s troubled past.

Both men are soon enmeshed in the mystery of who killed the cop in the minimart, and engaged in a race against time to clear Kaden’s name. But when the mystery is solved and the bullets stop flying, they’ll have to deal with their personal complications… and an attraction that’s spiraled out of control.

Table of Contents

Amy’s Dark Contemporary Romance

To Mary. There’s not enough knitting in the world to show you how very blessed you’ve made me. And to Mate, because we read Lee Childs and I might get him to read Kathy Reichs. And to the kids, for being proud of me, even when I don’t talk a lot about what I do.

THANK YOU

so much

to Kim Fielding, who read this and said, “Uh, they’d be having this discussion in a jail cell, not an office,” and “You know, lawyers don’t type up nearly so many briefs.” And basically made me feel like I had a life preserver in the deep end of action/suspense fiction, because while I’m used to being neither fish nor fowl, I do like knowing how to swim.

“SHE WOULD

have hated this,” Jade said, pulling hard on a cigarette.

Jackson Rivers glared at his ex-girlfriend, the sister of his best friend, and one of four—no, three—people he actually cared about in the world.

Jade had promised her mother she’d quit, just like Jackson had.

“She would have hated you smoking,” he muttered.

“Yeah, well, if she didn’t like smoking so much, she should have quit before it gave her cancer.” Jade took an angry drag and tossed him a scowl. She usually wore microbraided extensions, but her mom had been sick for a long time while all of her “children” had been dealing with college—or, in Jackson’s case, the police academy. She hadn’t had any fucking time to get her hair done, so it was scraped back into a severe bun on the back of her head. Jackson hoped she’d have time again. She’d always loved shaking her braids back in high school, and he’d always thought it was sexy.

“Hey,” Jackson said, determined to do what Toni Cameron had asked of him. “I quit.”

Jade rolled her eyes. “Yeah, well, you only started to get with me, so that’s fair.”

Hell of it was, she was right. Jackson would have done anything to fit in with Jade and Kaden’s family. Smoking was no big deal.

“Dammit, Jackson, make her quit smoking.”

Jackson turned his head and looked over the headstones in the old graveyard off Auburn Boulevard.

And smiled. “I couldn’t make her stop when we were together,” he said mildly, and then he went in for the hug.

Kaden Cameron, his oldest and best friend, and Kaden’s wife, Rhonda, whom he’d known almost as long, stood there, and God, it was good to see them. Especially the granite presence that was Kaden. Six feet five inches of solid family man, with brown eyes so limpid and wide, Jackson used to think he could see the future in them.

And that was

before

Jackson realized he was bi.

He’d never crushed on K, though. Jade, yes, because Jackson and Jade were birds of a feather. But K represented something bigger, more important to Jackson than a potential lover.

In sixth grade, Jackson had been forging his mother’s signature on the free-lunch form when Kaden had asked him to pass up his math. Jackson had accidentally passed up the form instead.

No big deal—in their school, 98 percent of the students needed that form, and the other 2 percent were too stupid to forge the signature.

But Kaden had passed the paper back and said, “Your math, idiot. And don’t get too excited about lunch—they’re serving mystery enchiladas today.”

Jackson closed his eyes and fought a groan. “Man, last time I had the runs for a week!”

“No shit.” They both looked nervously up at the teacher to see if she’d heard the profanity, but she was too busy dealing with that one kid who always freaked out and started throwing chairs.

“Well, thanks for the warning. At least I’ll get some bread and milk.”

Kaden grunted. “Yeah, me too. But hey—my moms is cooking a chicken tonight. Come knock on our door at six. But she’s gonna make you pray. You can’t get mad.”

Jackson blinked. “Who gets mad at praying for food?”

“I don’t know. Don’t care. Just, you know. Be nice to my moms.”

“Course.” Even Jackson knew that when someone’s moms was doing a good thing, you showed respect.

That night Jackson left his mom in a cloud of smoke—tobacco and something else that made his heart race and his eyes blur—and walked up the shaky concrete stairs to the apartment four units over. He knocked on the door and wished he could wash the smell out of his hair.

The woman who greeted him looked young—younger than his mom, and he knew his mom was way too young to have him. Her hair was up in glossy black curls, some of which spiraled down to frame her face.

And she wore a home-sewn business skirt and a sleeveless shirt, like the women in the courtroom dramas on TV.

Toni smiled at him just like TV moms too. And she fed him, and when he took too much and Kaden told him he was being a pig, they needed leftovers, she told him to go ahead and eat extra. Just this once.

It was the last time Jackson did that, because God, he was just so grateful for the food.

Toni Cameron became his savior. He didn’t expect mothering, so she kept her touch light. For holidays, she bought an extra shirt and an extra pair of jeans for him so he wasn’t always dressed in shit with holes. It was from the bargain bin, but so was Kaden’s, and he liked that he and K dressed the same.

It made him feel like he belonged somewhere.

By the time he could emancipate himself and move in with the Camerons, he had a job, and he paid her rent as often as he could, because he didn’t want to take advantage. The shame of eating too much chicken that first night never fully left him.

Toni had done her best to fix that.

He’d been almost through the academy by the time she’d gotten sick, and she’d been so proud of him. The day he’d graduated, Jade and Kaden and Rhonda had pushed her wheelchair to the front of the Memorial Auditorium so she could watch Jackson walk the stage. They were all in school, but they had about two more years to go—this was her chance to see one of her kids graduate.

Jackson had been so glad to see her there, so happy to go out to dinner and sit with her, that he hadn’t told her about his misgivings. Hadn’t told her that the man who’d sponsored him through the academy seemed to expect things Jackson couldn’t give—things that went against every hard-earned concept of ethics Jackson had ever acquired.

He’d put on a good face for her.

He’d put on a good face for them all.

And she’d asked him, soberly, to quit smoking that night, for her. He’d told her, soberly, that he would—and omitted the fact that he’d had to quit just to get through the academy without dying of asphyxiation, because the academy was too rigorous to wreck your body. Fact was, his promise to Toni would keep him clean.

In so many ways.

“Kaden,” he said, his voice thick with emotion. “God, man, I’m so sorry.”

Kaden’s chin quivered. “We’re all sorry, Jacky. She was your mom too.”

He closed his eyes. God, she was. She really was, in all the ways that counted. He hadn’t been easy to mother—it was hard to cuddle with an alley cat—but damned if she hadn’t tried.

“She was the best,” he said gruffly. “Your mom was the best.”

“I know,” Kaden said, and Rhonda hip-checked him aside for her hug.

“You look thin, Jacky,” she said softly.

Kaden’s wife was lovely. Not quite as dramatically complexioned as Jade and Kaden, she had an oval face with a strong jaw and an aquiline nose, and bold lips that smiled way more than Jade’s ever had. Rhonda Cameron had only kind words for anybody, and she was going to make a fantastic teacher.

After she made a fantastic mother.

“I’ll take back the weight when you’re through with it,” he said, patting her three-month baby bump. Dammit, Kaden, for not remembering the rubber! Rhonda was the smartest of all of them—Jackson knew she’d make it—but they just had to add the extra level of difficulty, didn’t they?

“I’ll hold you to that,” Rhonda said softly and then stroked his cheek. “But you still don’t look good. It’s only been a couple of months since you graduated, Jacky. Is the job that awful?”

Jackson wanted to throw himself in her arms and sob.

Yes. Yes, dammit. The job was that awful. The things Patrick Hanover wanted him to be a part of were awful. The things he was doing to stop Patrick Hanover were awful.

Toni Cameron was going in the ground today, and it felt like the entire world was gray and putrid, because there was only so much good out there, and a big chunk of gold light had been wasted away to ash-colored skin and bone by lung cancer.

“I’ll be fine,” he said, his throat almost too thick to speak, and Jade grabbed his hand right then because it was time to go listen to the preacher man say words that Toni Cameron had loved.

Jackson stood still and silent during the service, not listening at all. He was too busy fighting a grand battle in his heart over the things he wanted to tell his family and the things he couldn’t.

Jade needed to go back to school.

Kaden and Rhonda needed to finish and make a home for their baby.

This thing Jackson was doing—this really important, terrifying, dangerous thing—was to keep people like his family from getting hurt by people they should trust.

The Cameron family had saved Jackson when he’d been a skinny kid who’d just wanted chicken. Toni Cameron had used what precious little money she’d had to feed him and clothe him. Even before he’d moved out, he’d been able to sleep on her couch when his own apartment had been a little slice of hell.

Jackson owed them. He owed them everything, from simple survival to graduating from high school to getting through the academy. He owed them for his belief that people could be good and that good people could be happy.

He owed them the world.

Jackson would do anything to keep the Camerons away from the corruption that was eating him alive.

After the service they all went out to Hometown Buffet, because they were hungry and none of them had money for anything better. Jackson ate two helpings of chicken in Toni’s honor and told Rhonda he’d be sure to remember to eat.

GOING HOME

that night had been so hard.

He’d taken advantage of a union program and put money down on a duplex as soon as he got his first paycheck from the force. On his days off, he’d fixed the paint, repaired the roof, that sort of thing, and he’d just started looking for a tenant.

That night he’d gone into his still-bare little side of the house and listened, just listened, for a heartbeat somewhere within.

Valerie had broken up with him two weeks ago, right before Toni died, and he couldn’t blame her. He hadn’t said a word to her of what was up, why he came home shaking, why his temper was so uncertain.

There was nobody there. Not a lover, not a friend, not his family—and there couldn’t be. Not until this thing was over.

Feeling more alone than he ever had in a shitty and abusive childhood, Jackson Rivers slid down the wall of his hallway until he was sitting with his legs sprawled on the floor.