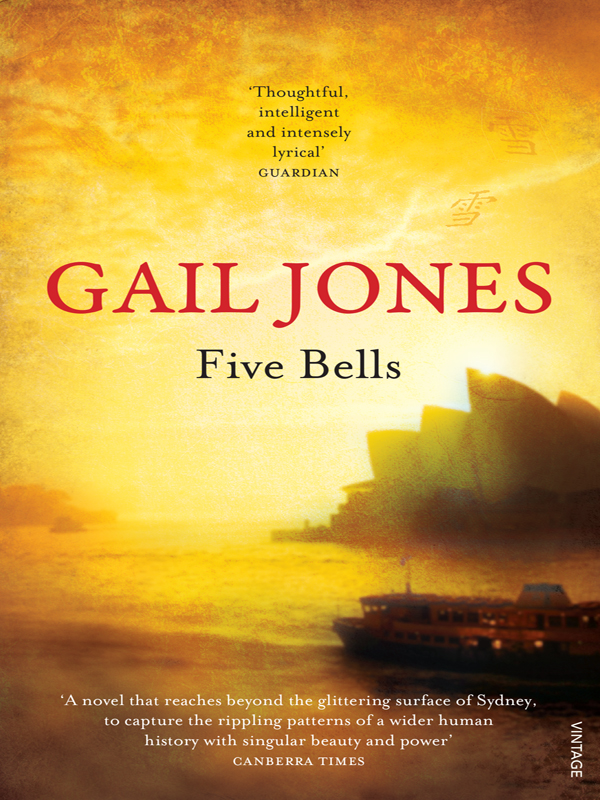

Five Bells

Authors: Gail Jones

Winner of the Kibble Literary Award, Shortlisted for the Victorian Premier's Prize for Fiction, the Adelaide Festival Award for Literature, The ALS Gold Medal, the Barbara Jefferiss Prize and the Indies Award.

On a radiant day in Sydney, four people converge on Circular Quay, site of the iconic Opera House and the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Each of the four is haunted by memories of the past: Ellie is preoccupied by her experiences as a girl, James by a tragedy for which he feels responsible, Catherine by the loss of her beloved brother in Dublin and Pei Xing by her imprisonment during China's Cultural Revolution. Told over the course of a single Saturday,

Five Bells

describes vividly four lives which chime and resonate. By night-time, when Sydney is drenched in a rainstorm, each life has been transformed.

Memory believes before knowing remembers

William Faulkner,

Light in August

Where have you gone? The tide is over you,

The turn of midnight water's over you,

As Time is over you, and mystery,

And memory, the flood that does not flow.

Kenneth Slessor, âFive Bells'

Circular Quay:

she loved even the sound of it.

Before she saw the bowl of bright water, swelling like something sexual, before she saw the blue, unprecedented, and the clear sky sloping upwards, she knew from the lilted words it would be a circle like no other, key to a new world.

Â

The train swung in a wide arc to emerge alongside sturdy buildings and there it was, the first glimpses through struts of ironwork, and those blurred partial visions were a quiet pleasure. Down the escalator, rumbling with its heavy body-cargo, through the electronic turnstile, which captured her bent ticket, then, caught in the crowd, she was carried outside.

There was confusion at first, the shock of sudden light, all the signs, all the clamour. But the vista resolved and she saw before her the row of ferry ports, each looking like a primary-colour holiday pavilion, and the boats, bobbing, their green and yellow forms toy-like, arriving, absorbing slow lines of passengers, departing. With a trampoline heart she saw the Bridge to her left: its modern shape, its optimistic uparching. Familiar from postcards and television commercials, here now,

here-now

, was the very thing itself, neat and enthralling. There were tiny flags on top and the silhouetted ant forms of people arduously climbing the steep bow. It looked stamped against

the sky, as if nothing could remove it. It looked indelible. A

coathanger

, guidebooks said, but it was so much grander than this implied. The coherence of it, the embrace, the span of frozen hard-labour. Those bold pylons at the ends, the multi-millions of hidden rivets.

Â

Ellie gawked like a child, unironic. She remembered something from schooldays: Janus, with his two faces, is the god of bridges, since bridges look both ways and are always double. There was the limpid memory of her schoolteacher, Miss Morrison, drawing Janus on a blackboard, her inexpert, freckled hand trailing the chalk-line of two profiles. With her back to the class, there was a kind of pathos to her form. She had thickset calves and a curvature of the spine and the class would have snickered in derision, had it not been for her storytelling, which made any image so much less than the words it referred to.

Roman God

: underlined. The Janus profiles not matching. A simple image on the blackboard snagged at her feelings and Ellie had loved it because it failed, because there was no mirror and no symmetry. And because the sight of Miss Morrison's firm calves always soothed and reassured her.

Â

From somewhere drifted the sound of a busking didgeridoo with an electronic backbeat,

boum-boum, boum-boum; boum-boum, boum-boum

. The didgeridoo dissolved in the air, thick and newly ancient.

For tourists, Ellie thought, with no disparagement. For me. For

all

of us.

Boum-boum, boum-boum

.

In the democratic throng, in the pandemonium of the crowd, she saw sunlight on the heads of Americans and Japanese; she saw small children with ice-creams and tour groups with cameras. She heard how fine weather might liberate a kind of relaxed tinkling chatter. There was a news

stand, with tiers of papers in several languages trembling in a light breeze, and people in booths here and there, selling ferry tickets behind glass. There was a human statue in pale robes, resembling something-or-other classical, and before him a flattened hat in which shone a few coins. A fringe of bystanders stood around, considering the many forms of art.

Janus

, origin of

January

.

Ellie turned, like someone remembering, in the other direction. She had yet to see it fully. Past the last pier and the last ferry, there was a wharf with a line of ugly buildings, and beyond that, yes, an unimpeded view.

Â

It was moon-white and seemed to hold within it a great, serious stillness. The fan of its chambers leant together, inclining to the water. An unfolding thing, shutters, a sequence of sorts. Ellie marvelled that it had ever been created at all, so singular a building, so potentially faddish, or odd. And that shape of supplication, like a body bending into the abstraction of a low bow or a theological gesture. Ellie could imagine music in there, but not people, somehow. It looked poised in a kind of alertness to acoustical meanings, concentrating on sound waves, opened to circuit and flow.

Yes, there it was. Leaning into the pure morning sky.

Ellie raised her camera and clicked.

Most photographed building in Sydney.

In the viewfinder it was flattened to an assemblage of planes and curves: perfect Futurism. Marinetti might have dreamt it.

Â

Unmediated joy was nowadays unfashionable. Not to mention the banal thrill of a famous city icon. But Ellie's heart opened like that form unfolding into the blue; she was filled with corny delight and ordinary elation. Behind her, raddled train-noise reverberated up high, and the didgeridoo, now barely

audible, continued its low soft moaning. A child sounded a squeal. A ferry churned away. From another came the clang of a falling gang-plank and the sound of passengers disembarking. Somewhere behind her the Rolling Stones â âJumping Jack Flash' â sounded in a tinny ring-tone.

Boum-boum

, distant now,

boum-boum, boum-boum

, and above it all a melody of voices, which seemed to arise from the water.

Ellie felt herself at the intersection of so many currents of information. Why not be joyful, against all the odds? Why not be child-like? She took a swig from her plastic water-bottle and jauntily raised it:

cheers.

She began to stride. With her cotton sunhat, and her small backpack, and this unexpected quiver in her chest, Ellie walked out into the livelong Sydney day. Sunshine swept around her. The harbour almost glittered. She lifted her face to the sky and smiled to herself. She felt as if â yes, yes â she was breathing in light.

James DeMello was obstinately unjoyful. Even before the rattling train pulled into the station, he knew in his bones that he would be disappointed. He glanced at the leather hands of the old woman sitting beside him and felt the downward tug of time, of all that marks and corrodes. They resembled his mother's hands, the sign of a history he did not want. So much of the past returns, he thought, lodged in the bodies of others.

James rose from his seat to escape the hands and stood clutching a cold metal pole. The train swung in a wide arc around sturdy buildings and through his limbs he felt the machine braking and the stiffening of bodies encased in steel. When the carriage doors opened he followed the man in front

of him, moving towards the down escalator with his hands in his pockets.

At the foot of the escalator everyone swung out onto the quay, a mobile mass, subservient to architecture. Before him were ferry ticket-boxes hung with LED light timetables in orange and people of assorted nations, queuing for a ride. There was a tawdry quality, he decided, and too little repose. A child squealed and he felt an elemental flinch of annoyance; the rest was cacophony and the vague threat of crowds.

Turning to the right, James walked automatically, trailing behind others. There were shop-fronts decorated with arty souvenirs, there were little white tables with empty wine-glasses, there were waiters clad in black aprons and haughty dispositions. It was too early for lunchtime and they were in merely indolent preparation. A man stood with his arms crossed, scowling, emphatically doing nothing. James thought of Sydney as inhabited by a tribe of waiters, a secret society of men and women united by their contempt for those they served, and with rituals of smug superiority and arcane rules. They met mostly on Mondays, when many restaurants were closed, and engaged in ceremonial meals at which they spilled food and swore.

Umbrellas bearing coffee-logos fluttered in the breeze. James skirted one, then another, wondering if he needed caffeine.

Then he saw it looming in the middle distance, too preempted to be singular. It appeared on T-shirts, on towels, even trapped in plastic domes of snow; it could never exist other than as a replication, claiming the prestige of an icon. Its maws opened to the sky in a perpetual devouring.

White teeth, James thought. Almost like teeth. And although he had seen the image of this building countless times before, it was only in its presence,

here-now,

that the analogy occurred to him. The monumental is never precisely what we expect.

At an Easter Show, long ago, he had seen the yawning jaw of a shark, the great oval of an inadmissible, unspeakable threat. Death was like that, he knew, shaped in ivory triangles. Death was the limp panic of imagining oneself as raw meat. Or even less than that; just a shape to be ravaged, just a drifting, edible nothing in blood-blurry water.

At the entrance to the carnival tent, a sign read âMonsters of the Deep' and an old codger with filthy stubble and an aspect of decay ushered him in by lightly touching the back of his head. He can still see the moment, those teeth gleaming in the brown light, bleak and distressing. He can still smell it: the reek of stale tobacco and unwashed clothes, and an acidic stench, as though someone had pissed in a corner. When the tent flap fell closed with a soft

pffth

, sealing him in, James felt sure he would die there, swallowed into darkness as in the belly of a beast. Superstitious and afraid, he had placed his feet in a slender triangle of sunlight falling through the entrance. He glanced from his shoes to the teeth and back again; shoes to teeth, teeth to shoes. He could not look at the shark-jaw entirely, nor could he resist looking. He was a child terrified by what his imagination might suggest.

The stinking man moved up behind him and James felt a hand on his back. He froze there, submissive, and looked only at his shoes, aligned with tied laces in the slash of lemon light. And then, twisting free, James turned and fled. He pushed at the flap of the tent, panicking, and fell forward onto his face.

Why, he wondered now, does time shudder in this way, and return him always to this inadequate boy that he was, in short pants, and afraid, and seeing white teeth in a jagged vision? The experience of a few minutes, years ago, and no doubt an exaggeration.

James turned, pissed off by this ridiculous memory-siege.

No, no, no. Coldplay's âClocks' swam into his head: â

closing walls and ticking clocks

' â it was the curse of his generation, to have a soundtrack enlisted for everything.

Â

James turned away and walked back down the pier. He saw the Bridge, he saw the ferries, he saw the peach-coloured façade of the gallery of contemporary art; it was hung with red banners advertising something or other. His gaze was listless, remote. Considering these sites unremarkable, dull in his own livid space, James turned his back to the Harbour and retreated to a café, as if he needed to defend himself from what might entertain others. People swept around him, each with their own thoughts, each â the idea was fleeting â with their own apprehension of what might undo a single life, teeth, a touch, a brown space held in time by a gape of open canvas. But the crowd was a collective, and indistinct. They were unconnected to him. They were blithely autonomous. The

masses

, he liked to call them.

In the blue shadows of the café James found an empty chair with its back to the window. He was feeling slightly ill. He was feeling implausible. A waiter with a pumice complexion and a lank pony-tail took his order, professionally cool, and then slid away. One of the secret society, perhaps, a smarmy condescender. Chatter rose with the clack of cutlery and the chink of teacups, the infernal din of the coffee machine and the roar of steaming milk. Beyond that, what was it? The summer of Vivaldi's

Four Seasons

playing in a jangled slur. How he hated this: music treated as a background accessory.

When his espresso arrived with a glass of water, James swallowed a tab of Xanax, sucking down his own misery. Chemistry, he thought, to change errant chemistry. To be neurally synthetic, to be in biochemical kilter, to concoct homeostasis from this haggard sick self. He might look in a mirror and be startled by a handsome return. He might yet recover.

Every sound was amplified; the café was no retreat at all. The glass walls were percussive and strangely radiant. A rack of grimy magazines, from which smooth faces pouted, leant against the wall for the customers' lazy perusal. Everywhere around him James saw detritus â a serviette crushed into a flowery ball, ring-pulls from drink cans, a chocolate bar wrapper, its form origami, torn sugar sachets, food scraps, the bits and pieces of commercial junk people left everywhere in their wake, setting a litter trail, as in a fairytale, to be found in a mythical dark wood.

Someone had left a tiny pyramid of sugar poured on the table. James pressed it flat with his index finger and thought he might sob.

The traditions of the dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living

. A favourite quote. Karl Marx. 1852.

Even the coffee was bitter.