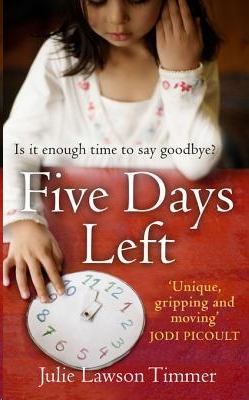

Five Days Left

Authors: Julie Lawson Timmer

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Julie Lawson Timmer

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Timmer, Julie Lawson.

Five days left / Julie Lawson Timmer.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-698-14086-8

1. Terminally ill—Family relationships—Fiction. 2. Families—Fiction. 3. Farewells—Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction. 5. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3620.I524F58 2014 2013048485

813'.6—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For Ellen

ART

I

Tuesday, April 5

FIVE DAYS

LEFT

Mara

Mara had chosen the method long ago: pills, vodka and carbon monoxide. A “garage cocktail,” she called it. The name sounded almost elegant, and sometimes, when she said it out loud, she could make herself believe it wasn’t horrifying.

It would still be horrific for Tom, though, and she hated herself for that. She would rather do it without leaving a body for him. But as much as she’d love to spare him from being the one to discover her, she knew not letting him find her would be worse. And at least this was the tidiest option. He could have someone come and take her car away. Fill her side of the garage with something else, to block the image. Bikes, maybe. Gardening supplies.

A second car for himself. Maybe she should arrange to have one delivered after. Would that be too weird, though? A gift from your dead wife. She should have given him one years ago. For their anniversary, or to celebrate bringing baby Lakshmi home. Or just because. She should have done so many things.

Mara frowned. How could it be that she had spent almost four years ticking off all those items on her long list of things to do before she died, yet here she was, five days from it and still thinking of things she should have done?

Ah, but that was the trick of it. Tell yourself you’ll wait until you’ve accomplished every last thing and you’d keep putting it off. Because there would always be one last thing. Which might be fine for someone who had the luxury of delaying a few more weeks, or months, or years even, until they were finally out of excuses and ready to go through with it.

Mara didn’t have that luxury. In less than four years, Huntington’s disease, the mother of all brain cell destroyers, had already done more damage than she and Tom could have ever prepared for. She had the severance papers from the law firm to prove it. The once graceful, athletic body that was now slow to react, reluctant to cooperate.

If she allowed herself to experience that one more moment with her husband and daughter, to travel to that one last must-see destination, she might wake the next morning to find it was too late, and Huntington’s was in control. And she would be trapped in the terrifying in-between of not being able to end her life on her own, and not truly living, either.

Time was against her. She couldn’t risk waiting any longer. She could make it to Sunday, as she had planned. But she couldn’t wait past then.

Mara took a long swallow of water from the glass on her bedside table and stood. Inhaling deeply, she reached to the ceiling with both hands and focused on the bathroom door across the room. It was tempting to cast her eyes up toward her hands, the way the move was supposed to be executed, but she had gotten cocky before and the hardwoods always won. She counted to five, exhaled and tilted forward slightly, pressing her hands toward the floor for another count of five. A Sun Salutation modified beyond recognition, but enough to clear the fog from her brain.

The hiss of the shower stopped and Tom emerged from the bathroom, toweling his dark hair. “Good morning,” she said, eyeing his bare torso. “You’re wearing my favorite outfit, I see.”

He laughed and kissed her. “You were out cold when I got up. I was

planning on asking your parents to come over and get Laks on the bus.” He tilted his head toward the bed. “I can still call them, if you want to catch a few more hours.”

Laks. Mara’s throat closed. She reached the dresser and put a hand on it to steady herself. Turning away from her husband, she pretended to fuss over some spare change and loose earrings on the dresser. She swallowed hard and coaxed her throat into releasing some words.

“Thanks, no,” she said. “I’m up. I’ll put her on the bus. I need to get moving myself. I’ve got errands to run.”

“You don’t have to run errands. Why don’t you write out a list and I’ll get anything you need on my way home.”

He walked to the closet, pulled on dress pants, reached for a button-down. She made a furtive wish for him to choose blue but his hand found green. She would try to remember to position a few of his blue shirts in front so he would reach for one before the end of the week and his cobalt eyes would flash one more time.

“I’m capable of running a few errands, darling,” she said.

“Of course you are. Just don’t push it.” He tried to sound stern, but his expression showed he knew she would take orders from no one.

He put on his belt—third hole—and she shook her head. He hadn’t gained a pound in twenty years. If anything, he was in better shape, logging more miles in his forties than he had in his twenties, a marathon a year for the past ten. She supposed she could take some credit for it, since these days he ran partly to manage stress.

She walked to the door, lightly touching his shoulder as she passed him. “Coffee?”

“Can’t. Patients in twenty.”

A few minutes later, she felt him wrap his arms around her from behind as she stood at the kitchen counter, inserting a premeasured coffee pack into the coffeemaker. Loose grounds tended to end up on the counter or floor rather than in the filter these days.

Tom kissed the back of her neck. “Don’t do too much today. In fact,

don’t do anything at all. Stay home, take it easy.” He turned her around to face him and smiled in defeat. “Don’t do too much.”

Mara watched him disappear into the garage. She willed her breathing to slow and her eyes to stop burning. Turning to the coffeemaker, she made herself focus on the

plip, plip

of the coffee as it dripped into the pot, the scent of hazelnut, the steam rising from the machine. She set a cup on the counter, filled it halfway and gazed at it longingly. As tempted as she was to take a sip, she had learned to let it cool. Her hands couldn’t be trusted to stay steady, and it was better to have only a stain to clean than a burn to soothe. Calmer, she made her way down the hall to her daughter’s room and peeked in the doorway. A small head lifted drowsily from the pillow and a wide grin, gaping in the middle where four teeth had recently gone missing, greeted her. “Mama.”

Mara sat on the bed, spreading her arms wide, and the girl climbed into her lap, pressing her body close and gripping tightly around her mother’s neck.

“Mmmm, you smell so good.” Mara buried her face in her daughter’s hair, freshly clean from last night’s bath. “Ready to take on another day of kindergarten?”

“I want to stay with you today.” The little arms clutched tighter. “Not letting go. Not ever.”

“Not even if I . . . tickle . . . right . . . here?”

The small body collapsed in a fit of giggles and the arms loosened their grip, allowing Mara to wriggle away. She stood, took a few steps toward the door and, calling forth her best “Mommy means business” look, pointed to the school clothes laid out on the glider chair in the corner of the room.

“All right, sleepyhead. Get dressed and brush your hair, then meet me in the kitchen. Bus comes in thirty minutes. Daddy let you sleep late.”

“Oh . . . kay.” The child stood, stepped out of her pajamas and walked to the chair.

Mara propped herself against the door frame, pretending to supervise

so she could steal a few precious seconds watching the waif whose skinny, olive-colored frame still took her breath away.

As she dressed, Laks sang one of her rambling songs, a play-by-play of what she was doing, set to her own meandering tune. “Sprite music,” Mara and Tom called it.

“Then, I put my jeans on,

with the flowers on the pockets,

and a pink shirt,

that is so pretty.”

She stepped away from the chair and did a pirouette, arms raised above her head, hands in “fancy position,” as she had seen the big girls do at ballet school. Striking a final pose, she looked at her mother and smiled triumphantly. Mara forced her trembling lips into a smile and, not trusting her voice, held up a hand, fingers spread wide, indicating the number of minutes the girl had to make her way to the kitchen.