Fixing the Sky (23 page)

Authors: James Rodger Fleming

His lobbying efforts eventually paid off, though, and the army provided funds for an initial field test. In the summer of 1921, Warren contracted for electrical work to be done by the physicist Chaffee at Harvard's Cruft High Tension Electrical Laboratory. Chaffee examined the theoretical basis for charging small particles with high voltage, built a generator that would run off an aircraft motor, and designed the best way to disperse the sand, which he determined was through an electrically energized nozzle and the prop backwash.

10

Warren arrived in Dayton on September 7 and began to install equipment on the aircraft. The army paid to bring Chaffee out at $25 a day plus expenses, but Warren chose to stay off the payroll to protect his business rights, since he was then in the process of applying for multiple international patents. The U.S. Army Air Service provided him with two planes, pilots and observers, a car and driver, a stenographer, and a coordinating officerâMajor T. H. Bane. Not all was going smoothly, however. Warren had fallen behind on payments to his creditors and, as usual, was writing to Bancroft seeking financial aid “to help me out of this mess.” His plan was to “go above detached clouds and try to cause precipitation in the form of trailing rain. We should be able to pull this stunt off within ten days, I hope.”

11

10

Warren arrived in Dayton on September 7 and began to install equipment on the aircraft. The army paid to bring Chaffee out at $25 a day plus expenses, but Warren chose to stay off the payroll to protect his business rights, since he was then in the process of applying for multiple international patents. The U.S. Army Air Service provided him with two planes, pilots and observers, a car and driver, a stenographer, and a coordinating officerâMajor T. H. Bane. Not all was going smoothly, however. Warren had fallen behind on payments to his creditors and, as usual, was writing to Bancroft seeking financial aid “to help me out of this mess.” His plan was to “go above detached clouds and try to cause precipitation in the form of trailing rain. We should be able to pull this stunt off within ten days, I hope.”

11

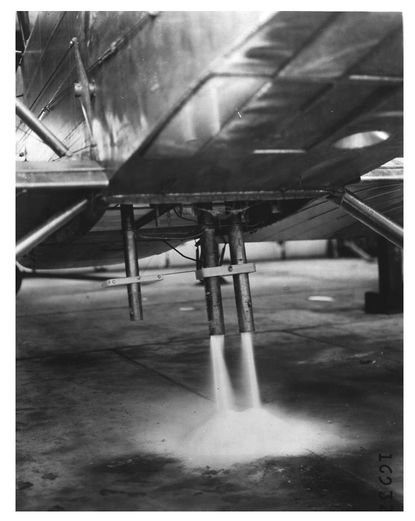

In the “stunts” (they can hardly be called experiments), a La Pere plane flying above the cloud tops sprinkled sand charged to approximately 10,000 volts by an on-board wind-driven generator. The electrified sand was dispensed through musket-shaped nozzles (figure 4.1) and further scattered across the clouds by the action of the airplane's propeller. Sometimes, but only sometimes, these aerial “attacks” opened clearings in fair-weather cumulus clouds or dissipated them completely. Although the stated goal of the project was to clear airport fogs and generate rain, no tests were conducted on low-level stratus or nimbus clouds. Other than a dramatic exhibition of the prowess of aviators (it was known at the time that the backwash from propellers alone could bust up clouds by mixing them with surrounding drier air), nobody knew why the electrified sand technique should work.

Alluding in vague terms to small-scale smoke-clearing demonstrations under laboratory conditions, Warren offered up some technical mumbo jumbo about the effect of electrified sand particles accelerating the “free electrons in a mass of air.” He told the press and his patrons (but never published) his theory that “each electron attaches itself to a certain number of molecules and so forms a gas ion, upon which moisture condenses, thereby making a cloud particle.”

12

He claimed that his technique produced “a so-called trigger action, forcing the elec-trical

charge in the cloud to change from a static to a kinetic state that will rapidly spread or flash over the whole clouded area from the spraying of only a few pounds of dust over a small part of a highly charged storm movement and force precipitation when the wet bulb conditions are favorable over the dry section” (3). By changing the polarity of his generator, he said, he could reverse the process and produce “a large hole, in a fraction of a minute ... through the entire cloud from top to bottom” (3). Of course this is gobbley-gook, akin to the unsupported technical claims invoked by the charlatan rain fakers. When asked why he was intercepting only fair-weather clouds, Warren cited the absence of suitable fog in Dayton and the danger of flying through rain clouds, since all were “highly electrified and it was not deemed safe to deal with them with high voltage until measures were taken to guard against possible accidents to the pilots and planes” (3).

12

He claimed that his technique produced “a so-called trigger action, forcing the elec-trical

charge in the cloud to change from a static to a kinetic state that will rapidly spread or flash over the whole clouded area from the spraying of only a few pounds of dust over a small part of a highly charged storm movement and force precipitation when the wet bulb conditions are favorable over the dry section” (3). By changing the polarity of his generator, he said, he could reverse the process and produce “a large hole, in a fraction of a minute ... through the entire cloud from top to bottom” (3). Of course this is gobbley-gook, akin to the unsupported technical claims invoked by the charlatan rain fakers. When asked why he was intercepting only fair-weather clouds, Warren cited the absence of suitable fog in Dayton and the danger of flying through rain clouds, since all were “highly electrified and it was not deemed safe to deal with them with high voltage until measures were taken to guard against possible accidents to the pilots and planes” (3).

4.1 Fog dispersal apparatus: sand being discharged through nozzles that are carrying a potential of 10,000 volts. (NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO B8241)

Aviation pioneer Orville Wright, who worked at McCook Field, witnessed one of the test flights through his office window and sent a telegram to the

New York Times

. He testified that he saw aviators cut to pieces three cumulus clouds in ten minutes, but saw no rain fall: “Having little knowledge of meteorology and

the other sciences involved in the experiment, I do not wish to be understood as expressing any opinion as to the practical value of the experiment nor of the possibilities that may develop from them.”

13

Navy commander Karl F. Smith was also watching. His memo, “Dr. WarrenâRainmaker,” noted that as an observer he was “not gullible and had remained skeptical,” but seeing a cloud split in two by the technique was “absolutely uncanny.”

14

The military applications were obvious. Smith envisioned special-purpose “clearing ships” for enhancing aerial navigation by dissipating fog or for cutting holes in clouds for bombing operations while keeping the main cloud bank intact for cover. Although he was not fully convinced, he thought Warren's technique “so important” that, after a few more trials, the U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics should either present it to the Patent Office or purchase outright Warren's rights and retain them for military purposes. Had Warren agreed, he could have cashed in on his invention then and there. Instead, he reserved his rights, immediately formed the A. R. Company (for “Artificial Rain”), and issued Bancroft 1,000 shares of stock at $5 a share. He also filed a U.S. patent application for “Condensing, Coalescing, and Precipitating Atmospheric Moisture.”

15

New York Times

. He testified that he saw aviators cut to pieces three cumulus clouds in ten minutes, but saw no rain fall: “Having little knowledge of meteorology and

the other sciences involved in the experiment, I do not wish to be understood as expressing any opinion as to the practical value of the experiment nor of the possibilities that may develop from them.”

13

Navy commander Karl F. Smith was also watching. His memo, “Dr. WarrenâRainmaker,” noted that as an observer he was “not gullible and had remained skeptical,” but seeing a cloud split in two by the technique was “absolutely uncanny.”

14

The military applications were obvious. Smith envisioned special-purpose “clearing ships” for enhancing aerial navigation by dissipating fog or for cutting holes in clouds for bombing operations while keeping the main cloud bank intact for cover. Although he was not fully convinced, he thought Warren's technique “so important” that, after a few more trials, the U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics should either present it to the Patent Office or purchase outright Warren's rights and retain them for military purposes. Had Warren agreed, he could have cashed in on his invention then and there. Instead, he reserved his rights, immediately formed the A. R. Company (for “Artificial Rain”), and issued Bancroft 1,000 shares of stock at $5 a share. He also filed a U.S. patent application for “Condensing, Coalescing, and Precipitating Atmospheric Moisture.”

15

When the story was initially reported in the newspapers, cartoonists immediately got to work. One set of panels published in the

New York World

fantasized about using the technique for raining out Sunday baseball games, ruining a rival's new hat, fighting fires, disrupting parades, and selling umbrellas (figure 4.2).

New York World

fantasized about using the technique for raining out Sunday baseball games, ruining a rival's new hat, fighting fires, disrupting parades, and selling umbrellas (figure 4.2).

In March 1923, one month after the initial publicity, U.S. Weather Bureau librarian and widely read weather popularizer Charles Fitzhugh Talman reported that meteorologists remained unconvinced by the Dayton tests.

16

In a weather bureau press release, William Jackson Humphreys contrasted the puny efforts of the rainmakers with the enormous scale of the atmosphere and called their techniques “entirely futile.” He compared the techniques of Bancroft and Warren with those of earlier rain kings: “The idea of the college professor and his aviator friends out in Cleveland, to sprinkle electrically charged sand on a cloud while above it in an airplane, is picturesque and plausible,” he noted, “but won't work in commercial quantities.”

17

Given the enormous forces at work in the atmosphere, Humphreys warned farmers in arid regions not to pay out their good money for so-called rainmaking devices: “Wet weather a la carteâthe dream of meteorologists, farmers, and umbrella salesmen for a good many yearsâis still an empty mirage.”

18

In response, Bancroft wrote: “No use arguing with Weather Bureau. Prefer to wait for results and let them do the explaining.”

19

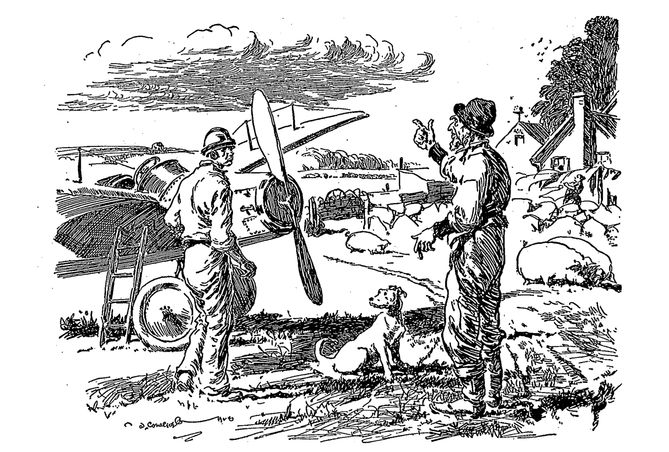

A cartoonist captured the tension between the new high-tech possibilities and domestic farm life, with the grizzled older man representing both worlds (figure 4.3).

16

In a weather bureau press release, William Jackson Humphreys contrasted the puny efforts of the rainmakers with the enormous scale of the atmosphere and called their techniques “entirely futile.” He compared the techniques of Bancroft and Warren with those of earlier rain kings: “The idea of the college professor and his aviator friends out in Cleveland, to sprinkle electrically charged sand on a cloud while above it in an airplane, is picturesque and plausible,” he noted, “but won't work in commercial quantities.”

17

Given the enormous forces at work in the atmosphere, Humphreys warned farmers in arid regions not to pay out their good money for so-called rainmaking devices: “Wet weather a la carteâthe dream of meteorologists, farmers, and umbrella salesmen for a good many yearsâis still an empty mirage.”

18

In response, Bancroft wrote: “No use arguing with Weather Bureau. Prefer to wait for results and let them do the explaining.”

19

A cartoonist captured the tension between the new high-tech possibilities and domestic farm life, with the grizzled older man representing both worlds (figure 4.3).

4.2 “Rain to Order”: lampoon of possible applications of rainmaking using electrified sand. (CARTOON BY AL FRUEH, IN

NEW YORK WORLD

, FEBRUARY 15, 1923; BANCROFT PAPERS)

NEW YORK WORLD

, FEBRUARY 15, 1923; BANCROFT PAPERS)

The May 1923 issue of

Popular Science Monthly

described the WarrenâBancroft demonstrations and hyped the story: “Think of it! Rain when you want it. Sunshine when you want it. Los Angeles weather in Pittsburgh and April showers for the arid deserts of the West. Man in control of the heavensâto turn them on or shut them off as he wishes.”

20

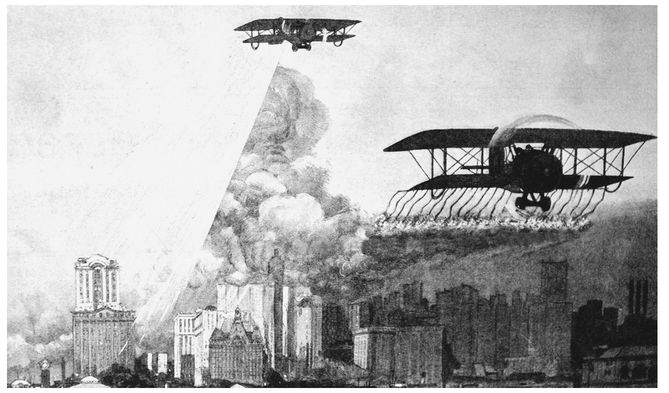

In an illustration, an electrified plane turns smog over a city into artificial clouds, while a second plane clears the air by generating artificial rain (figure 4.4).

Popular Science Monthly

described the WarrenâBancroft demonstrations and hyped the story: “Think of it! Rain when you want it. Sunshine when you want it. Los Angeles weather in Pittsburgh and April showers for the arid deserts of the West. Man in control of the heavensâto turn them on or shut them off as he wishes.”

20

In an illustration, an electrified plane turns smog over a city into artificial clouds, while a second plane clears the air by generating artificial rain (figure 4.4).

Warren claimed that a number of practical applications were just over the horizon: clearing the smoke from cities, removing London fogs, intervening in the course of naval battles, bringing rain to the farmers. As he explained it, the electricity generated by falling sand and rain would cause more rain to generate in the adjacent clouds and set off the entire heavens, much in the manner of a long fuse, thus causing widespread rains. Bancroft, who had been supportive all

along, yet constantly worried about the expenditures, doubted this. Concerned about possible lawsuits downwind of their operations, he recommended that they conduct field trials not over cities but over the Atlantic Ocean, both as a safety precaution and as an opportunity to experiment on marine fogs.

along, yet constantly worried about the expenditures, doubted this. Concerned about possible lawsuits downwind of their operations, he recommended that they conduct field trials not over cities but over the Atlantic Ocean, both as a safety precaution and as an opportunity to experiment on marine fogs.

4.3 “The Rain Makers”: “Go up and bust that there cloud over th' ten-acre field, Noahâbefore somebody else gets it; an' fer th' love o' peace, keep off th' ol' woman's washin'!” (“THE RAIN MAKERS,”

LIFE

, APRIL 5, 1923, 24)

LIFE

, APRIL 5, 1923, 24)

4.4 The way scientists propose to manufacture clouds and rainfall: “The first plane, trailing sparking antennae, condenses the soot and moisture laden air into a cloud by scattering electric charges. The second plane turns this cloud into rain by spraying it with electrically charged sand.” (MCFADDEN, “IS RAINMAKING RIDDLE SOLVED?”)

Round 2: Aberdeen and BollingIn March 1923, seeking better access to government patrons, Warren moved the test flights to the Aberdeen Proving Grounds, on the Chesapeake Bay northeast of Baltimore. It was an adequate but not ideal site. Only about a third of the area was available for tests, since the army's gun-firing range was given first priority. There was no machine shop or other manufacturing facilities, so Warren purchased commercial transformers, which turned out to be too heavy to fly and more costly than originally budgeted. Other delays were caused by problems with workers, a continual lack of funds, and an inordinate amount of red tape.

After more than a year of struggles and setbacks, on July 8, 1924, a plane from Aberdeen carrying Warren's equipment encountered an intense thunderstorm over the mouth of the Susquehanna River. The crew of two aviators reported: “Immediately following the attack [with 10 pounds of negatively charged sand] there was no more lightning or thunder, and a gentle rain of over one hour's duration followed, purely local.”

21

Warren claimed that this result was far from coincidental and that the plane's intervention had upset the electrical balance of the storm. More intense lobbying followed. On October 30, 1924, two planes equipped with electrified sand dispensers conducted a demonstration over Washington, D.C. Warren sent messages to President Calvin Coolidge, members of his cabinet, and members of Congress to “watch” as the planes “attacked” the clouds over the city. There is no record from eyewitnesses, but Warren noted, “We scored a most deplorable failure, as not a thing happened” (5). Disappointed but not deterred, Warren moved his operations closer to Washington, to Bolling Field. Less than a month later,

Time

reported a subsequent set of successful sanding demonstrations over Washington. Captain L. I. Eagle and Lieutenant W. E. Melville flew their De Havilland airplanes to an altitude of 13,000 feet, where they “shot down” a series of cumulus clouds with a barrage of electrified sand. As the planes circled overhead, a clearing opened up. “A miracle!” cried some of the watchers.

22

Still, although Warren had busted clouds, he had not yet cleared a fog or made it rain. Positive press clippings notwithstanding, Warren and his A. R. Company had not earned a penny on his invention, and Bancroft was still writing the checks.

21

Warren claimed that this result was far from coincidental and that the plane's intervention had upset the electrical balance of the storm. More intense lobbying followed. On October 30, 1924, two planes equipped with electrified sand dispensers conducted a demonstration over Washington, D.C. Warren sent messages to President Calvin Coolidge, members of his cabinet, and members of Congress to “watch” as the planes “attacked” the clouds over the city. There is no record from eyewitnesses, but Warren noted, “We scored a most deplorable failure, as not a thing happened” (5). Disappointed but not deterred, Warren moved his operations closer to Washington, to Bolling Field. Less than a month later,

Time

reported a subsequent set of successful sanding demonstrations over Washington. Captain L. I. Eagle and Lieutenant W. E. Melville flew their De Havilland airplanes to an altitude of 13,000 feet, where they “shot down” a series of cumulus clouds with a barrage of electrified sand. As the planes circled overhead, a clearing opened up. “A miracle!” cried some of the watchers.

22

Still, although Warren had busted clouds, he had not yet cleared a fog or made it rain. Positive press clippings notwithstanding, Warren and his A. R. Company had not earned a penny on his invention, and Bancroft was still writing the checks.

Other books

Chaos by Alexis Noelle

SHADOW OVER CEDAR KEY by Ann Cook

Tyger by Julian Stockwin

A Festival of Murder by Tricia Hendricks

The Royal Affair (The Palmera Royals) by Jane Beckenham

Damnation of Adam Blessing by Packer, Vin

Beautiful by Amy Reed

Outlaw Guardian by Amy Love

Pushing Limits by Kali Cross

The Devil's Fire by Matt Tomerlin