Flyaway (18 page)

Authors: Suzie Gilbert

TRAVELING FEET

There comes a time in every owlet's life when he decides it's time to hit the road. Complications arise when his feet are ready, but his wings are not.

“Hi, it's Wendy,” she said on the phone one April morning. “I have a little owl here, and he's reeeeaaaaally cute.”

“How cute?” I said. “And how little?”

“Well,” she said, in a philosophical tone. “He's cute and little for a great horned.”

Great horned owls are North America's largest species of owl. Although great grays appear to be taller, their added inches are really just feathers; they have the owl equivalent of big hair. Adult great horneds have legendary feather-covered feet that can exert a grip of approximately 250 pounds per square inch on whatever unfortunate creatureâor part thereofâthey manage to get in their grasp.

Wendy said that the owlet, which at four or five weeks old was too young to fly, had somehow ended up on the ground beneath its nest. The owlet was uninjured, which was remarkable for two reasons: one, because great horneds usually take over crow or hawk nests built near the tops of thirty- to fifty-foot coniferous trees; and two, because soon after it landed it found itself flanked by two large dogs.

Great horned owls lay two to three eggs and they don't hatch at the same

time, which means there can be quite a difference in the size of the chicks. The older they get the more jostling goes on, so it stands to reason that somebody occasionally gets elbowed out of the nest, or stands up and loses its balance, or decides to go for an ill-fated stroll. In any case, in a perfect world the chick would tumble to the ground, then hop onto a low branch or a fallen tree, where the parents would continue to feed and protect it. Unfortunately the owl's perfect world has been taken over by humans and their domestic pets, creating a whole new set of problems.

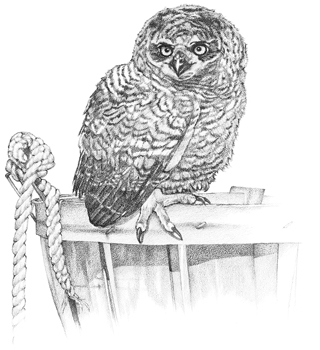

Luckily for this particular chick, the owner called off her large but gentle dogs, put the owlet into a box, and delivered him to the local animal hospital. When I arrived to pick him up, I looked into the box and reacted with the same complex set of emotions that most people experience when they first see a large nestling owl. The creature was incredibly cuteâsort of. Fuzzily soft and saucer-eyed, he also sported a black dagger of a beak and stood on huge feet tipped with lethal one-inch-long talons. His intense stare said: “Feed me or I'll kill you.” No problem, I said, and took him home to a waiting bag of mice.

The plan was to get the healthy owlet back to his parents as soon as possible, but meanwhile he needed to eat. The last thing you want a young wild owl to associate with food is a human, which precluded my leaning over his box, cooing and making kissy noises as I attempted to feed him. The solution was an owl puppet. By putting my hand all the way up into the puppet and manipulating its beak, I could pick up a small defrosted mouse. And by hiding behind the puppet I could ensure that the mouse was offered, not by a human, but by something recognizably owlish. A scared and hungry baby owl is usually more than willing to take comfort where it canâin this case, in something fuzzy, round-eyed, and holding a good meal by the tail.

Anyone seeing a nestling owl inhale a mouse will quickly realize that owls are the best friends a farmer could have. Owls are rodent-catching machines. They can hear tiny feet rustling through the grass a football field away, and gliding silently on softly fringed wings, will often snatch their prey before it even detects their presence. Young owls are ravenous, especially ones who have

missed a few meals. When my owl puppet dangled a mouse above the great horned nestling he lunged upward, seized the limp mouse by the head, and after a quick series of down-the-hatch motions, swallowed it whole. Three more received the same treatment; after the final mouse, the nestling settled down contentedly, eyes half shut, a long pink tail hanging casually out the side of his beak.

The kids snuck in to see him after he had fallen asleep. Eyes closed, talons covered by downy fluff, he looked like an angelic little cartoon football. “If you promise to do exactly what I say,” I whispered to them, “I'll let you feed him next time.”

Several hours later I handed Mac a mouse. Mac was born with a pragmatic worldview. He has always matter-of-factly separated the living from the dead, reasoning that once a creature has gone on to its great reward, somebody

should make a meal of it. Hiding quietly behind the owl puppet, he held a mouse by the tail and slowly lowered it over the owlet, who snapped it up without hesitation.

“Cool!” he said.

Skye's reaction was more complicated. During the winter she had viewed the burgeoning “raptor section” of the freezer in the garage with growing disapproval, eventually refusing to open the door lest she catch sight of something furry encased in a plastic bag. Although well versed in the intricacies of the food chain, she disagreed with its general principle. Always a champion of the underdog, she would have jumped in front of a Rottweiler to save the little great horned; now, however, the oppressed had become the oppressor. She stopped at the sight of the mouse, who, if truth be told, was quite small and cute.

“Sweetie, I'm sorry,” I said preemptively, “but I'm not the one who did him in.”

“You didn't do him in,” she retorted, “but you're serving him for dinner.”

When Skye feels combative, no argument on earth will win her over. I had already coveredâunsuccessfullyâthe balance of nature, the relationship between predator and prey, and the importance of the proper calcium-phosphorus ratio in raptor nutrition. Once I'd even burst into a chorus of “The Circle of Life,” which had served only to enrage her. With these recent defeats in mind, I veered off into the afterlife.

“If the mouse has already gone to mouse heaven, do you think he really cares what happens to his body? Maybe he'd be happy knowing he was helping a little owl.”

“Mouse heaven?” she repeated, giving me a withering stare. “Oh,

please.”

Late that afternoon I made a quick trip to the nest site, which turned out to be less than ten minutes from my house. The nest, a large and solid structure, was near the top of a forbiddingly tall hemlock to the side of a dirt road. Just visible above the edge of the nest was the downy gray head of the owlet's sibling, which meant that the parents were somewhere close by. With the exception of nesting northern goshawks, great horned owls are widely acknowl

edged to be the most ferocious raptors in North America. The problem: how to get a squirmy, uncooperative owlet forty-five feet up a tree without being maimed by its outraged parents. The solution: call Lew Kingsley.

The following morning Lew parked his car behind mine and squinted up at the hemlock tree.

“Mmm-hmm,” he said, scowling.

“Hootie!” I trilled, pulling the curtain away from the owl's carrier. “Say hello to your Uncle Lew!”

At the sight of the owl, Lew broke into a wide grin. “Cute little guy,” he said. “Nice feet.”

Lew tied a weight to a long, thin rope, and without even appearing to aim, tossed it into the air. As if by magic the weight sailed upward, threaded itself neatly around a branch five feet from the nest, and returned to earth. Lew tied the rope around the handle of a bushel basket partially filled with sticks and pine needles, and into the basket went the owlet. The basket would provide a safe and sturdy temporary “nest,” and because there were narrow gaps in the bottom, there was no danger of its filling up with water should it rain. When the parents came to feed one sibling, they'd find the other. Few old wives' tales have been more destructive than the one about parent birds refusing to accept nestlings touched by human hands; the parents just want their babies back, and with the exception of vultures, birds have a poor sense of smellâa fact which can be verified by anyone who has watched a great horned owl dig enthusiastically into a skunk dinner.

I couldn't spot either of the parents, although I was sure that at least one of them was no more than fifty yards away, watching intently, probably gauging how much of a threat we were to one chick and mystified by the sudden reappearance of the other. Had Lew tried to climb the tree and replace the missing chick, he might have ended up with one of the parents imbedded in the back of his neck, the possibility of which he was fully aware.

“Not the kind of bird I want gunning for me,” he said.

I slipped two mice into the basket next to the well-fed owlet, then Lew

hoisted the whole thing up and anchored it firmly. The sibling, who had poked his head over the side of his nest, watched the proceedings with interest. With any luck, the owlet would stay put until he was steady enough to hop out onto a nearby branch, and eventually to fly. That night I returned just before dusk. Standing next to the nest was one of the parents, dark and stately, glowering at me with huge yellow eyes. I could see the chick in the nest as well as the one in the basket. I returned the following day and found a similar scene. Thrilled by the fact that the owlet was still in the basket and not on the ground, I decided to hope for the best and leave them alone.

Unbeknownst to me, however, a few days later a construction worker drove by the nest site and found an owlet on the ground, once again flanked by large dogs. The construction worker was renovating the house of a family who lived a half mile up the road; he picked up the owlet, took it to work, and now, a week later, the owl was still living in the family's barn. The woman who called said she knew they shouldn't keep the owl and hoped any resulting problems could be remedied.

Although it is tempting to keep a baby raptor, it's a terrible idea. Unless you have a federal license, it's illegal; and unless you have a freezer filled with rodents and other assorted raptor food, the baby will develop metabolic bone disease and die. Should you decide to buy some frozen mice, keep the baby for a little while, and then let it go, you are still signing its death warrant: raptors are taught how to hunt by their parents, who continue to supplement them with food while they are honing their skills. A raptor who has no idea how to hunt and who has lost its fear of humans will either die of starvation or be killed when it approaches people for food. A raptor who grows up around children may decide to land on one when breeding season begins. Those whose kids are clamoring for a pet raptor should remember:

The Harry Potter books are works of fiction.

Fortunately for this owlet, the family temporarily hosting him recognized these potential problems and called me. Quite a bit larger than when I'd last seen him, the owlet was thin and more comfortable around people than he

should have been, but was otherwise relatively healthy. The family had named him Boo; on the way home I renamed him Boomerang, since he kept returning to me; by the time he was settled and I had hauled out the mice and owl puppet he was back to Hootie, my generic name for all owls; by the time he had scarfed down four mice in a row, he had no name at all.

“He doesn't get a name,” I told John. “He's supposed to be a wild owl. And he's going to be a wild owl if it kills me.”

“Right!” said John. “It's back to the woods for the little freeloader!”

If I could just get him back with his owl family fast enough he would forget his time among humans. But first he needed to fatten up, so there were four more days of recorded owl hoots, owl puppets, and endless servings of mice. When my supply of small mice started to run low, I depended on the kindness of friends, who couldn't bring themselves to set traps for the field mice racing around their houses until there was an actual need for it.

“Suzie!” came a whisper on the phone one evening. “It's Kurt RhoadsâI have a whole bag of frozen field mice for you, but I have to bring them over right now. My mother's visiting and if she sees them she'll have a heart attack.”

“Here,” said Wendy Lindbergh, appearing at my door one afternoon and handing me a gaily wrapped bag.

“Oh!” I said delightedly, picturing a bottle of girly hand lotion or flowery eau de toilette. “What's the occasion?”

“What do you mean, what's the occasion?” she said, as I pulled out a freezer bag filled with mice. “Isn't the owl hungry?”

Normally people feeding raptors do not feed them wildlife, as one can't be sure that the wildlife was completely healthy before it became a food source. But occasionally you can be almost sure, as with these strapping little field mice who had zero chance of having ingested anything toxic. I am lucky enough to live in a place where the majority of people are environmentally aware, wouldn't use poison if their lives depended on it, and are happy to help out when they can.

At dusk on the fourth day I drove to the nest site, trying to figure out how I

could once again reunite the footloose owlet with his family. By then he and his sibling were just about ready to start flying, but I couldn't guarantee that they could actually do itâand there were still the dogs to consider. I pulled over and looked up. Gazing back at me was the sibling, who had left the nest and was perched on a nearby branch, and an adult, who was probably the mother and did not appear pleased to see me. My delight immediately turned to apprehension: the two of them could fly away at any time, and my owlet would have no family to return to. I dove back into the car and raced home.