Food Over Medicine (26 page)

Read Food Over Medicine Online

Authors: Pamela A. Popper,Glen Merzer

GM:

I don’t see why even those who have a “tough love” attitude toward prisoners would object to feeding them very plain, simple, inexpensive foods like oatmeal, rice and beans, potatoes, corn, wheat, fruits, and vegetables. Prisoners certainly shouldn’t go hungry, so let’s feed them inexpensive, filling, starchy foods. None of the rich foods of royalty, like meat and fish and cheese. Why the hell would we feed meat and dairy, which require so much energy, water, and cost to produce, to people who have presumably committed crimes? Let’s put them on an inexpensive, low-fat, starch-based, plant-based diet; they’ll wind up being the healthiest population in the country. Shouldn’t this idea appeal to both conservatives and liberals? Let’s “punish” prisoners with cheap food that makes them healthy. And since they’re wards of the state, when they get healthy, that saves the taxpayers money.

PP:

Meat and dairy, unfortunately, aren’t as expensive as they should be. That’s the result of another public policy—farm subsidies.

GM:

And you’d favor ending them outright?

PP:

Yeah, let’s get rid of them.

GM:

I’d be fine with either of two outcomes. The first is the cleanest: get rid of all farm subsidies, as you say. Get government out of the business of picking the winners in agriculture—and it has effectively picked large-scale, animal agriculture interests—and turn it into a free market. Again, that’s an idea that should appeal to conservatives. I’d also be fine with subsidizing only crops raised organically and intended for human beings, not animals. Then at least our tax dollars would be helping farmers help the population get healthier, while incentivizing stewardship of the land.

PP:

The reason why it’s best to get government out of this completely, and you and I may have some philosophical differences on this score, is that I don’t think that government generally solves problems; I think more often it creates them. Once you propose that we’re going to subsidize this instead of that, who’s going to decide what to subsidize? How is that decision going to get made in a way that isn’t effectively corrupt? We cannot afford to continue to grow government. We cannot afford to continue to keep throwing money at problems. We can’t just build another USDA down the street staffed with different people who subsidize different farm crops and magically find a way to pay for it. We’re done. I’m all for government simply getting out of that business.

GM:

That would be more than fine with me. Another activity that perhaps the government should consider exiting is the business of issuing nutritional guidelines.

PP:

Absolutely. USDA has screwed it up beyond recognition and it’s not a productive use of the agency’s time. We’ve already discussed the problems with industry and agriculture influencing the USDA, but in preparation for a class that I teach, I visited the websites of a number of other countries that issue dietary guidelines. I spoke in South Africa last year, so I went to the South African government’s website where it promotes dietary guidelines. I’ve looked at Australia and several different countries.

GM:

Is any country doing a good job of it?

PP:

No, and for very familiar reasons—they’re pressured by the same political influences from food and agricultural groups that we are here. If we can’t find a model government policy anywhere on the planet that manages to eliminate this level of influence and provide impartial information to the public, maybe we should just get the government out of the dietary recommendations business. It can’t be any worse than the status quo.

GM:

Actually, I hope you’re right about that last point, but I wonder: As misguided as the current guidelines are, if there were no guidelines at all for school lunchrooms, would some states begin serving children meals that are 50 to 60 percent fat? In other words, are we better off with lousy guidelines that are the product of tacit corruption, or no guidelines at all? It’s a head-scratcher for me.

I think I’d favor retaining a role for government in issuing guidelines, but moving it from the USDA to the surgeon general’s office. And then all we’d have to do would be to get Dr. John McDougall or Dr. Neal Barnard appointed surgeon general and we’re good.

PP:

If we could be guaranteed that these men or someone like them would be in that position, I’d be all for it. The problem is there are only a few doctors in the country who understand these issues and are capable, in my opinion, of doing the right thing. The likelihood that one of them would be appointed is not great. In fact, a few years ago, PCRM resolved to influence the appointment to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee of some nutrition professionals with no ties to industry. PCRM submitted several highly qualified names; not one was appointed. Given its track record, we’re better off getting government out of it.

GM:

The other guidelines that are crucial to consumers are the labeling laws that govern what is written on the packages of food we buy. Bold health claims are made about various types of foods, and the nutrition labels can be confusing. What should be done?

PP:

The most important thing that we could do would meet opposition from food manufacturers, but it would be a simple law to draft and pass. The law would simply tell manufacturers of foods that the only thing they can do is put the ingredients on the label. In other words, a manufacturer can say it’s delicious and it smells great, but it can’t make any nutritional or health claims about the product. That would stop all this silly game-playing in which manufacturers take a stick of margarine that’s 100 percent fat, fortify it with plant sterols, and say it’s good for lowering cholesterol. The next thing I’d recommend doing would be to reduce the nutrition facts label to the basics: calories and calories from fat. That’s it.

GM:

What about people who need to restrict sodium? Shouldn’t they know how much sodium is in a given food? Or, for the sugar-sensitive, how many grams of sugar are in food? Or cholesterol content?

PP:

Sodium would be listed in the ingredients list, as would animal foods. We teach our members to pay attention only to the ingredients list and to avoid products with long lists of ingredients, many of which are not recognizable as food. It works.

GM:

Medicare remains the most debated, the most complex, and certainly the most fiscally significant public health policy issue. It’s easy to imagine someone writing a scholarly tome exploring all the complexities of the program and analyzing in a thousand pages a raft of competing ideas on how to keep it afloat. Not so easy to imagine anyone actually reading that book. Meanwhile, journalists and policy wonks debate the issue endlessly, politicians rant and rave and posture, and nothing gets done. So, to save everyone a mountain of time and trouble, and to save the country from tens of trillions in increased deficit spending in the coming decades, I say that we try to solve the problem in a few minutes here.

Labels should be simple and easy to read. The current, complicated label system costs a fortune as federal agencies are forced to spend time reviewing labels, policing manufacturers, and responding to lawsuits filed by manufacturers over claims that are denied. And consumers are still left with a label that few people pay attention to and many don’t know how to interpret.

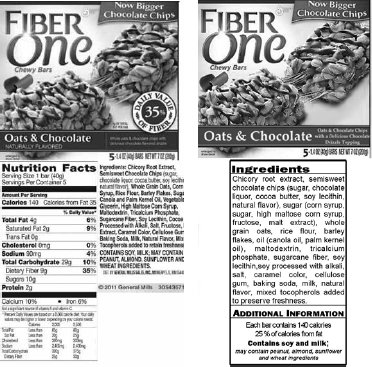

On the left is the front and back of the package of a popular product. On the right is my proposed version. Since no health claims would be allowed if my rules were adopted, the front of the box would not mislead people into thinking that this product promotes good health because of its fiber content (the fiber is due to added fiber from chicory root, not because the ingredients are high in fiber), and the term “naturally flavored” would not be permitted.

“Nutrition Facts” charts would not appear on the back of the box, which would prevent misrepresentation about the amount of fiber. Sugars and oils would be grouped together, making it easier for consumers to see just how much of these ingredients are in the product.

With this simpler label, consumers would readily see that the front of the box shows essentially a picture of a candy bar, and the ingredients list is consistent with a candy bar. Some consumers would still buy it because it tastes good, but more would not consider it a health food.

PP:

Happy to help.

GM:

Medicare’s fiscal nightmare looms because of a combination of factors:

- Demographics, with an aging generation of baby boomers (eighty million people will be on Medicare by 2040);

- A sick and obese population of seniors made unhealthy by unhealthy food; and

- A health care system geared toward incessant, expensive testing, often followed by expensive intervention.

As we know, high-tech medical intervention doesn’t always lead to better health outcomes, but it does always lead to higher costs; in the case of Medicare, those costs are borne by the taxpayers. The trend is unsustainable, to say the least.

I believe a decent society provides its senior citizens with an affordable, accessible system of medical care. I don’t want Americans to lose the Medicare entitlement. But it’s simply unsustainable on the present path. So here’s my suggestion: society should have a pact with its senior citizens. If you’ve paid into Medicare during your working life, we will take care of you in your retirement years. If you’re sick, Medicare will continue to cover your costs if you need to go to the doctor or the hospital. But an endless hunt for medical problems should not be part of that compact. Nor should most interventions consequent to that hunt. If you’re a senior citizen and you for some reason want a “preventive” colonoscopy or mammogram or stress test or angiogram or prostate-specific antigen test or vitamin D test or EKG or Dexa scan, it should be on your dime. If you are asymptomatic, but your preventive testing leads to an intervention (other than removal of a tumor or polyp), let that be on your dime, too. If we end Medicare as a discretionary testing benefit, we may save enough money to keep the program solvent for many more years. And I suspect it’ll save lives as well.

My parents had a very good friend who was about ninety years old. She went to a doctor complaining of chest pain, so the doctor proposed an angiogram. During the procedure, they nicked her aorta and she died a few days later. It’s unconscionable. They could have just put her on a low-fat, plant-based diet, but instead they killed her, and charged it to the taxpayers.

When my father, who at this point was a frail old man in his late eighties with Parkinson’s disease dementia, passed out at home, we made the mistake of calling 911. The medics took him to the hospital, where he remained for a week, ostensibly to combat his orthostatic hypotension. They ran every test on him imaginable. He was a frail, dying old man who didn’t even know what state he was in—when asked that question by his neurologist, I swear he said “confusion”—but the one thing he knew was that he wanted to get out of the hospital. They ran one test after another on him and billed the taxpayers $70,000 for it. They still didn’t stabilize his blood pressure, but they did give him a urinary tract infection from the catheter. I was wracked with guilt for putting him in the hospital. So the next time he passed out, we kept him home and took care of him until he came to. One thing I’m proud of is that we allowed him to die at home; he never saw a hospital again.

PP:

The disturbing fact is that the overtesting and overtreating we’ve discussed before is especially targeted at the senior population. The situations you described with your family and family friend are not isolated incidents.

Neil Armstrong died as a result of complications of bypass surgery at the age of eighty-two. As I mentioned before, only a tiny fraction of bypass surgeries in the United States are medically warranted; the procedure is even less useful and more dangerous in people over the age of eighty.

5

But after a routine stress test that Armstrong failed, he underwent a quadruple bypass. Although we’ll most likely never know the details of the conversation he had with his cardiologist, I would be willing to bet that the discussion did not include the recommendation to adopt a low-fat, plant-based diet or a recommendation to read Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn’s book, both far less expensive alternatives to bypass surgery. It would be hard to believe that Armstrong would have opted for bypass had he been informed properly of the risks and minimal benefits of the procedure and the potential benefits of plant-based nutrition.

GM:

Pam, how would you save Medicare?

PP:

The way to make Medicare sustainable is to stop paying for tests and procedures that have no basis in science. You mentioned before that society should take care of health care for its seniors. I agree. Here’s how we could do it in a way that would have a positive effect on all payers. We should incorporate the findings of independent research groups like Cochrane into the decision-making process. For example, Cochrane’s research, which is extensive, shows that mammograms are inadvisable for any group. For every woman saved, six women die unnecessarily. Neither Medicare nor any other entity should pay for mammograms. If you want a mammogram, you can pay for it yourself, but neither the government nor insurance companies should pay for those tests. Same with Dexa scans, PSA testing, colonoscopy, and other diagnostic tests. And the same would hold true for treatments. If Avastin does not add a single day of survival for breast cancer patients, it simply would not be reimbursable. You could pay for it yourself if you were convinced you wanted it.