Forensic Psychology For Dummies (21 page)

Read Forensic Psychology For Dummies Online

Authors: David Canter

Perhaps you argue that most people don’t commit crimes because they’re afraid of being caught. Evidence exists that property crimes can be cut by making burglary and robbery more difficult to carry out and easier to detect, something I talk about in Chapter 8. Violent crime is more likely to be a product of the personality of the offender and the culture he’s part of, including having some of the personality disorders I discuss in the section ‘Investigating Mental Disorder and Crime’ earlier in this chapter. A person who relates well to others and can control his temper, in a society where violence isn’t tolerated, isn’t likely to commit violent crimes.

Of course, most people are good citizens because they’ve been brought up to observe the law and so avoid committing crimes. However, there are people out there committing crimes who are never caught and charged. So, exactly what proportion of the community is likely to commit a crime in the knowledge that they can get away with it, despite knowing right from wrong, is an open question.

Just about every psychological aspect of criminality I talk about in this chapter is present to some degree in most of the population – and with most people having been convicted of nothing more than a traffic offence.

Factoring in protective factors

So many things can cause a person to become a criminal; the list is long. But if you’d like a broader sociological perspective get hold of

Criminology For Dummies

by Stephen Briggs (Wiley) where you can find out a lot more about the causes of crime, such

as deprivation and class conflicts. Yet people earmarked as potential criminals don’t all turn out bad. There are certain aspects of daily life – known as

protective factors –

that help to cut the pernicious influences that can give rise to a person becoming a criminal:

Close relationship with a family member:

Feeling alone in the world is an ingredient for believing that you don’t need to accept society’s restraints. A close relationship with a family member or a teacher you admire gives you roots in the community and the feeling of self-respect that can prevent you from drifting into crime.

Good educational environment:

Education is the key to so much in a person’s development even if you’re not brilliantly clever. Enjoying a level of educational attainment gives you self-respect; the ability to express your own capabilities protects you from a life of crime.

Job satisfaction:

If you like your job, you’re more likely to experience self-worth and also you’re less likely to want to risk losing your job by committing a crime.

Positive relationships with non-criminals:

Beyond the satisfaction that comes from having good relationships with individual family members and teachers, being part of an overall group of law-abiding individuals is as much a barrier to criminality as being part of a criminal gang is a pathway into the underworld of crime (see the earlier section ‘Keeping bad company’).

Sociability:

If you get on with other people and relate to them well, you feel confident in yourself and are more able to resist the temptations of undesirables and bad company. Crime becomes less attractive as an option.

Of course, knowing right from wrong does help to keep people on the straight and narrow. But that knowledge comes from the people you mix with.

Lacking the opportunity

Absence of opportunity is a good way of preventing a crime being committed. One school of thought argues that society can tackle crime by using

target hardening

: that is, reducing the opportunities and possibilities for crime to a minimum. Target hardening is about making a crime more difficult to carry out, such as having measures in place to make it harder to steal and defraud and the perpetrator believing he can get away with it. I explore target hardening in more detail in Chapter 8.

Fearing being caught

Punishments for crime exist to deter people from committing the crime. But the punishment only has any power if people think that they’re going to get caught. Therefore, the effectiveness of law enforcement is important in stopping people becoming criminals.

When a person commits a crime and gets away with it, he’s developing criminal skills and is more likely to be on the path to a criminal career. Some people have similar characteristics to a criminal but direct these personal traits into something more socially acceptable; for example, the hard-headed businessman who takes advantage of others without having any feelings of guilt for the consequences. The suggestion has been widely canvassed that some people who are successful in the cut-throat world of big business are best thought of as

psychopaths

– people lacking in empathy who callously and without remorse insist on getting their own way.

Aging: ‘I’m too old for all this!’

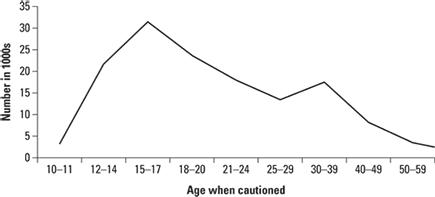

The good news is that aging can act as a deterrent to crime. There comes a stage in life when you feel committing a crime simply isn’t worth the effort. Crime is a young person’s activity (see Figure 2-1). Physical prowess, risk- taking and believing you can get away with it and not end up in prison is typical of young men, a way of thinking not nearly so common in older people.

If a person commits a crime early in life, he’s likely to suffer the consequences and wants to put that experience behind him. A settled lifestyle with a spouse and children is a good enough reason to avoid taking risks and any possibility of doing time in prison.

Figure 2-1:

An example of age distribution of offenders cautioned in English courts in 2002